The ComScore report released Tuesday that propped up Facebook as a worthwhile avenue for advertisers to consider underscores what most social media observers have known for quite some time: Not all customers – and not all fans – of a company or brand are created equal.

The biggest problem is that traditional advertisers have treated Facebook and other social networks as traditional media: Something where a click should have a measurable return on investment. Advertisers who “get” social media understand that it’s about strengthening relationships with their biggest fans, and hoping those fans can turn their friends onto the product as well.

The ComScore report is littered with the phrase “Fans and Friends of Fans,” signaling the strong emphasis successful brands are taking to cater to the people who can implicitly endorse them to others. If one of your friends is a fan of Starbucks, you’re more likely to be exposed to a Starbucks message on Facebook. And if you’re exposed to a Starbucks message on Facebook, you’re 38% more likely to make a purchase in the next four weeks.

But too many brands, the report argues, still focus on accumulating the most number of likes instead of figuring out how best to engage those fans. It’s not to say that fan accumulation isn’t important; it is the crucial starting point. But too many brands treat it like an end game instead of a first step in getting to the real end game – the return on investment of time and money in building a social media presence.

The other big problem – and one we delved into last week – is that there is still no reliable way to measure the return on investment. Analytics companies are getting better at tracking whether engaged fans eventually make a purchase decision, but brands are still, by-and-large, forced to look at the number of clicks a brand page feeds to its website.

Traditional Metrics Downplay the Power of Amplification

The report said the focus on click-through rates of display ads and brand pages on Facebook downplays the impact that has on a user’s friends and followers.

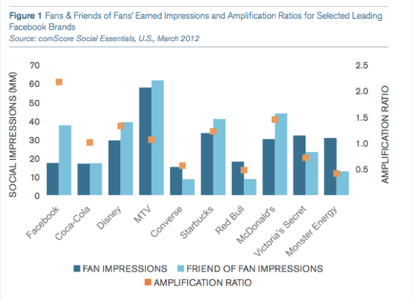

“The idea behind amplification is that Fans who are reached with brand messages can also serve as a conduit for brand exposure to Friends within their respective social networks,” the report said. “Because the average Facebook Fan has hundreds of Friends, each person has the ability to potentially reach dozens of Friends with earned impressions through their engagement with brand messages.”

In fact, ComScore said, if the top 1,000 brands maximized amplification efforts, they would have an amplification rate of 81. As it stands, the top 10 brands on Facebook had an average amplification rate of 1.05.

What the ComScore Report Can’t Measure

ComScore offers up a compelling holiday shopping case study, showing that fans of a brand spent more than average at the brands they like. In some cases, such as Amazon.com and Best Buy, spending was almost twice as high as the average purchase at the retailers. That makes sense; what is more telling is that friends of those fans also spent more, on average, at the same retailers.

But here’s the rub, as acknowledged by the report (if largely ignored by the Facebook-cheering tech press):

“While this research adds weight to the importance of social media, it also brings an important questions to the forefront – are the elevated spend levels among Fans and Friends of Fans the result of the messaging or a predisposition among these segments? Put another way, if relying solely on this data, the age-old “correlation or causation” question would be left very much unanswered.”

In other words, am I spending more at Best Buy because my friends like it, or because I hang out with people who are into tech gadgets? Am I 38% more likely to get coffee at Starbucks in the next four weeks because I saw a friend liked the brand on Facebook, or am I 38% more likely to get coffee at Starbucks because I run with people who like Starbucks – whether or not they choose to publicly declare so on Facebook?

Most likely, it’s a combination of both, as well as other factors including traditional advertising and proximity. In my case, I end up drinking more Starbucks than I’d like because it’s the only passable coffee shop within walking distance to my house. It’s a decision that I feel better about, perhaps because so many of my friends implicitly endorse Starbucks by liking the company on Facebook.