This post first appeared on the Ferenstein Wire, a syndicated news service; it has been edited. For inquires, please email author and publisher Gregory Ferenstein.

Google’s entire multi-billion dollar software utopia is designed to find the perfect search result. Back in 2005, before U.S. and EU government regulators painted Google as a monopoly, now-Chairman Eric Schmidt was quite open about the search giant’s end game. He said that Google should ultimately only give one search result for each inquiry—the right one for you at that moment.

“When you use Google, do you get more than one answer? Of course you do,” he told public television host Charlie Rose at the time. Schmidt continued:

Well, that’s a bug. We should be able to give you the right answer just once. We should know what you meant. You should look for information. We should get it exactly right.

This complicates the EU’s current antitrust case against Google. Among other objections, European regulators charge that when Google prioritizes its own services and partners in search results, it’s snuffing out the competition.

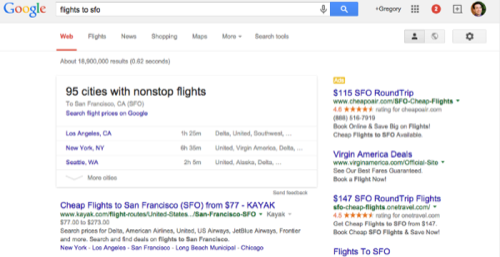

Google routinely does this, placing certain items above the search results, such as when consumers are looking for flights or hotels. In the screen shot below, flight search engine Kayak loses out to Google’s own suggestions.

One of Google’s leads on artificial intelligence, futurist Ray Kurzweil, told me that the company should eventually predict answers before users even know to ask them. He calls this Google’s “cybernetic friend” — software that knows you better than you know yourself.

This could be fantastic for consumers. If we’re searching for headache treatments, Google could alert us to a flu epidemic in town. If we’re concerned about housing policy, Google could tell us about an upcoming county board meeting. It could make us healthier, more productive and civically engaged.

But by design, Google search is on a path designed to exclude, or at least shoulder aside, search results it considers suboptimal to its own. Whether or not that technically puts Google in violation of antitrust law is a matter for the lawyers; things could get murky when it uses its search-engine dominance to favor sponsored results—also known as ads—over results from, say, competing travel services.

Either way, it suggests there may be a fundamental collision looming, with new anticipatory-computing business models like the one Google is moving toward on one side, and traditional antitrust law on the other.

Lead image by Duncan Hull