The amount of texting we do is insane. It’s a trendline not likely to drop anytime soon, if the behavior of younger users offers any hints. Those adults-in-training known as teenagers send between 60 and 100 texts per day, according to the Pew Internet and American Life Project.

As more of our communication takes place on this plain, colorless form, it’s no surprise that people have begun to seek ways to flesh it out with some character. One increasingly popular way to do that is by using Emoji.

The emoticon-style set of graphical icons has actually been around for awhile. Young people and women in Japan have been actively using Emoji since the 1990s, says Mimi Ito, a cultural anthropologist at the University of California, Irvine. In recent months, it has begun to catch on with Western users, fueled in part by the inclusion of an Emoji keyboard in the latest version of iOS.

“It’s not accidental that Emoji developed and became popular in Japan, where there is a history of pictorial communication because of the use of Chinese characters,” Ito says. “It was the convergence of this linguistic history with the widespread adoption of text messaging that gave rise to Japan’s unique Emoji culture.”

From Texting to Instagram, Emoji Expands Outside Japan

In the United States, the use of Emoji appears to be dominated mostly by early-adopter types, or at least those with enough curiosity to go into their iPhone’s settings and turn on alternative keyboards. Previously, it could be used on iOS, Android and other platforms only by using third-party apps. But native support by one of the world’s most widely used mobile operating systems has, at the very least, begun to push Emoji slowly toward popular usage.

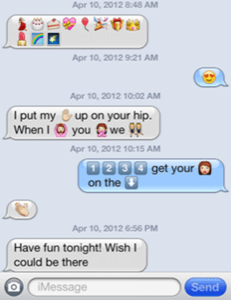

Most commonly, Emoji is used to enliven otherwise drab text messages with faces, animals, food, weather, buildings or any number of other tiny graphics.

However, it’s much more than just a bunch of emoticons. What’s interesting about Emoji is that it has actually begun to take on some qualities of a real language. In Japan, it didn’t take long for users to start stringing together Emoji characters to express ideas more complex than a single emotion or object. This gave rise to a basic sort of syntax, which in some cases allowed people to have entire – albeit, somewhat limited – conversations entirely in Emoji.

Why Not Just Call?

So, if people are eager to interject emotional cues and nuance into their conversations, why not just call each other? The answer has a lot to do with the contexts in which digital communication is embedded into our lives.

“In contrast to voice, text messaging and Emoji can be used in a much wider range of settings,” Ito explains. “And can be about side-by-side ambient communication rather than an exchange that requires full attention.”

For the vast majority of direct, remote communication we do, texting turns out to be far more convenient and efficient than calling somebody or initiating a video chat, which are increasingly reserved for longer or more deeply personal exchanges. Hence the 100-message-per-day habit of many young Americans, who are by no means alone in this regard.

In addition to text messages, the graphical character set has also found its way into popular social apps for smartphones. It’s not uncommon to see Emoji woven throughout comment threads under photos in Instagram, for instance, whether to interject a smiley face or to be used to express something more complex.

Emoji is starting to catch on outside Japan, but how likely is it to reach mainstream status in the United States? Not terribly, Ito says, even though “there does seem to be some demand.” The reasons have to do with linguistic differences between the two societies, as well as some technical niceties.

“Japanese smileys, or kaomoji, are much more elaborate than the U.S. smileys,” she says, “even though the U.S. has had the technological capacity to do more elaborate smileys for even longer than the Japanese have.”