The Domesday Book was a census, land and property survey carried out in England in 1086 for William the Conqueror. William presumably wanted to know what he owned and where it all was once he’d taken over England. It was an early landmark in law and a valuable artifact of English history.

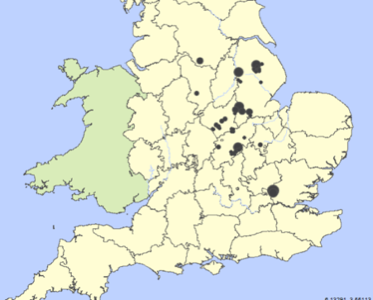

Now, PASE Domesday has made the entire book available online in an extensive database, including statistical and narrative information with all its locations mapped. Although it has been designed for academics, the public can read and search free.

PASE, which stands for the mellifluous “Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England Domesday,” is a collaboration between the Department of History and Centre for Computing in the Humanities, at King’s College London, and the Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic at the University of Cambridge.

The book itself was called “domesday” or “doomsday” for two reasons. First, it recorded the transition of property from the once-dominant Anglo-Saxons to the Normans who displaced them. Second, in its place as a cornerstone of English common law, once the book was referred to in a legal dispute, the judgment was final.

Speaking to Heritage Key, Cambridge Professor Simon Keynes, a co-director of PASE credited technology as the enabling element in the project.

“The breakthrough has been made possible by the wonders of modern technology, in selecting and arranging the data, in generating the maps, and in presenting the possibilities. One can then begin to detect the patterns and to make the informed judgements which will help to produce a significant result.”

Although the Domesday Book is a capstone in the project, it is far from the only online, mapped source in the database. It also encompasses various first-person sources, charters, narrative sources such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the Vita Ædwardi Regis, as well as prosopographical data from coins in the Fitzwilliam Library’s database of Early Medieval Coin Finds.

As information-rich as the database is, it is not, as the old phrase would have it, “user friendly.” To start a new search, you have to click a button called, weirdly, “Reset Constraints.” Some counter-intuitive scholarly criteria (like name “type”) need to be negotiated. It’s a great resource, but academics would do well to fold in some Web professionals when developing a site like this.

Domesday book from Wikimedia Commons