In a remarkable series of articles on the World Policy Institute’s blog, Anais Borja introduces this distressing thought.

“With easy storage made even easier by cheap disk space, our ability to create and save information has outpaced our ability to think critically about the theory and practice of archiving it.”

Will this increase in materials force a democratizing of information and impress that on future historians or will it create an epochal informational garbage dump where real understanding will defy human and machine thought?

The Scope

The information we’re dealing with has in fact increased to a scale we’ve never dealt with before, according to Google CEO Eric Schmidt.

“Every two days now we create as much information as we did from the dawn of civilization up until 2003. That’s something like five exabytes of data.”

Current archiving practice is turning toward the assimilation of “gray documents,” material that is made outside the pale of a given subject (governmental reporting and analysis created outside of government, the academy and journalism, for instance, like a blog or YouTube video of a politician having dinner at a restaurant). There is also a turn toward bringing material created online into an archive, such as the Library of Congress’s archiving of Twitter.

Even if Moore’s Law stays on track and computational abilities increase we’re already so buried in information that it’s hard to imagine how we’ll head it off and get our minds around it.

The Appraisal

Getting our minds around it may not strike most people as essential to archiving, but as Borja says, “the history of archival theory is the history of appraisal.” Without appraisal, there is no archive, there is only a data dump. And that’s the issue. How can we appraise the value of such a tremendous increase in data. Can we do that? Or is it destined to remain the important, but latent, shell midden of the information age?

Will context and provenance, hallmarks of archival science, be tossed by the wayside? Is there any way to keep them, thereby keeping archives “contextually based organic bod(ies) of evidence”?

Everyone looks at the world though their lenses. Archivists may hope for a sense of responsibility on the part of the public to the way their archives, their collected data, contribute to the historical record, that they will in fact act like archivists, that they will standardize their contributions to history. Despite the attempt of some companies to do so, people in general just won’t.

But that does not mean we producers of that radically increased data set don’t have a role to play. We have an obligation to recognize and support archivists and their end-users, historians, in the gathering and appraisal of information.

The Archivist

Information may seem pretty well organized to many. Go to Google. Enter search terms. Voila. But look up “awdyl gywth,” a Welsh poetic form on Google. Not a single hit. Google is a great tool, but it is not an archive, much less an exhaustive archive, and it’s up to us to recognize the difference.

A lot of the preservational tools archives use for Internet information are automated, spiders that crawl and copy based on a set of criteria. But this is not really appraisal. Any type of information can be useful to the historian, professional or amateur. But certain information is much more likely to be of value than others. The presence of human archivists may be more important than it ever was.

Any logical positivism of data collection is doomed. You cannot understand the world by duplicating it, and given the largely inaccessible deep web, you can’t even do that. But, having access to a tremendous amount of data, even if it is all informational, has an upside. For those who doubt or wonder at a given appraisal of history, more opportunities may exist for those people to do their own, deeper investigations. Thereby might we come a little bit closer to a democratization of history in our future. But it’s going to require a lot of digging in the midden.

We would like to hear from you. What information should we as a society save in the digital age? Given how much information there is, in even a restricted collection of online data, how can we, should we, appraise and evaluate what’s there? With so much information at our fingertips, do we need levels of appraisal to have a hope of making sense of our past, in the future, and our present now? What do you think.

Read more ReadWriteWeb coverage of archiving

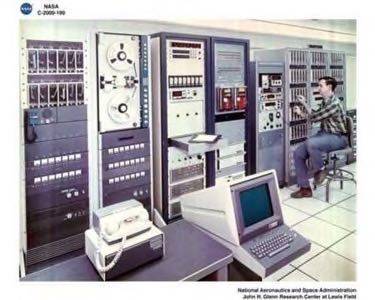

Cave photo by James Byrum | computer photo from NASA | quill photo by Evalia England