Depending on who you believe, the week long Spamhaus-Cyberbunker cyberattack we covered Wednesday was either a threat to the Internet itself or hyped up by an overzealous security vendor. Either way, it was still serious business.

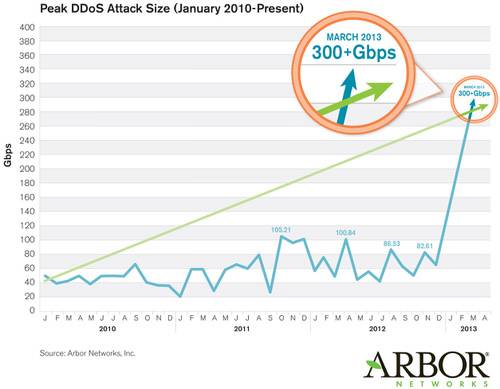

While much of the Internet disruption may have in fact been localized to Europe, and also potentially caused by tampering with underwater telecom cables in the Mediterranean, big DDoS attacks — that is, distributed denial-of-service assaults that aim to knock target computers off the Internet — are real, and have been on the rise since 2010.

Dan Holden, the director of ASERT, Arbor Networks‘ security engineering and response team, has been monitoring DDoS attacks for more than 12 years. In 2012 his company released a Worldwide Infrastructure Report that reports attack sizes have been peaking at around 100Gbps (check out this detailed look at the report here). This week’s attack was more than 300Gbps — way above the norm, in other words.

That’s because the attackers actually co-opted part of the Internet’s basic infrastructure — the Domain Name System, or DNS — in such a way as to greatly amplify the firehose stream of data they were directing at target computers.

Here’s how they work, according to Carlos Morales, Arbor Networks’ vice president of global sales engineering and operations:

Attackers send DNS queries to a [DNS server] on the Internet but use the victim address as the source of the query. When the response goes back, a response that is usually multiple times the size of the initial query, the response goes to the victim. Multiple this by hundreds of thousands of requests from bots on the Internet spoofing the one victim address and you get a very large flood of traffic to the victim machine.

Holden says DNS is becoming an increasingly popular target for DDoS. As many as 27 million DNS servers across the Internet are “open” in a way that allows them to be hijacked this way.

That means that while this week’s attack may not have knocked us Americans off of the Web, the amount of localized disruption overseas was definitely large enough to cause serious reverberations. This may not have been the Web’s D-Day, but these could definitely be the opening salvo of a hacker blitzkrieg. Let’s hope the ISPs and powers that be don’t Neville Chamberlain it.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock