ReadWriteHome explores the implications of living in connected homes.

Classrooms have historically been slow adopters of technology. When I was a young student, the latest blueberry iMac sat on my desk at home while my school library ran Oregon Trail circa 1990.

Today, as connected homes and advanced consumer technologies increasingly become part of our daily lives, the tools used in class often still lag behind. But some educators want to narrow this gap. So, to shape the future of education, they’re using the connected technologies available today to lay important groundwork.

Welcome to emerging world of the connected classroom.

Tools To Build The Connections

It wasn’t long ago that the connected home was a pipe dream envisioned by technologists. Now, it’s a reality—albeit a nascent one—with an ever-expanding list of devices and connected services to make the home smarter and more efficient.

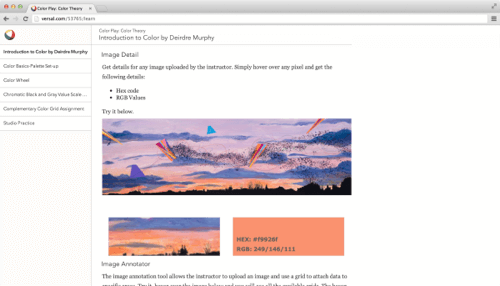

Likewise, some educators and administrators are relying on devices and connected services to improve the learning environment. Startup Versal, for example, aims to make lectures more engaging by helping teachers create interactive online courses easily, no coding required. For students, having immediate access to tutoring from the comfort of their living rooms could drastically improve homework completion and conceptual understanding.

“Our primary concern right now is creating better online education,” Versal CEO Gregor Freund told ReadWrite this summer. “Computers are designed for interactivity. We want to help teachers bring courses to life.”

To access those online resources, schools used to rely on stationary desktops and laptops as the backbone of their tech initiatives. Now tablets have stepped up to fuel digital education programs. According to a study by Pew Internet and American Life Project, 43% of Advanced Placement and National Writing Project teachers say tablet computers are used in their classes or to complete assignments. And as many as one in five school districts have rolled out Chromebooks as well.

Such services and gadgets offer mobility and ubiquitous connectivity, and that bodes well for the future of the connected classroom. Imagine homework prompts that automatically appear on students’ devices the moment they’re assigned. A tablet app that puts impending assignments front and center when a student enters study hall. Or a cloud service that knows a student’s interested in, say, science because he always does this homework first, or she has perfect attendance in that class.

Features like these are feasible given the state of technology today. And some schools have even begun collecting that type of data.

Tracking Student Data

Last year, the John Jay Science & Engineering Academy in San Antonio, Tex., kicked up a controversy among privacy advocates. Its Student Locator Project, which sought to monitor kids’ safety and location, tracked students using RFID chips embedded in school IDs. When a landmark federal court decision deemed it legal last January, the ruling opened the doors for broader student monitoring.

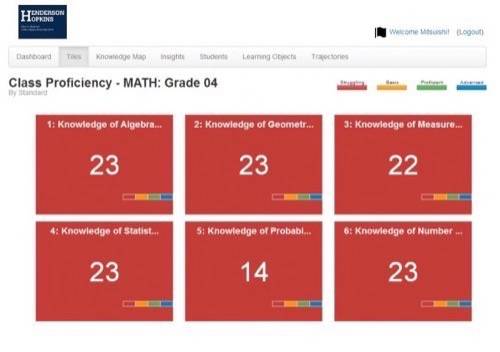

Another school, Henderson Hopkins in Baltimore, Md., just launched a program this year to see how various factors—such as community, commuting and attendance—influence classroom performance. Sponsored by the John Hopkins School of Education, the K-8 charter school worked with Catalyst IT, an agile software development firm, on a system that monitors student information.

“When you have a school that draws kids from a bunch of different backgrounds, knowing where a kid is on an absolute level doesn’t tell you that much,” Catalyst IT CEO Michael Rosenbaum explained in an interview. “What you want to know from a perspective of managing a school is, what’s the rate of improvement?” Ultimately, the goal is to predict trends and improve the quality of education on an individual basis.

For instance, the school maintains a database that tracks the bus lines students take, so it can check that data against attendance and academic records. If a student arrives late to school often, it can pinpoint whether the problem lies with the bus line or with the student’s personal motivation.

Currently Henderson Hopkins inputs data manually, but its future plans include wearable devices to automate some of the tracking. This will make it easier to evaluate other factors, such as social circles and whether friends have a negative or positive effect on a student’s education.

Such programs come with obvious concerns, particularly when it comes to the privacy of minors, but they also hold great promise. According to Rosenbaum, teachers have been embracing the technology, and response has been very positive so far.

Connecting The Dots

While the trends may seem disparate, taken together, they begin to form a picture familiar to those who follow connected home technologies. Just as smart kitchens, Wi-Fi-enabled thermostats and other appliances can collect information about how a person eats, when he or she comes and goes, or other lifestyle aspects, schools can use devices and data collection to get a more holistic view of how students learn and offer features that support it.

This prospect spurs initiatives like the Common Core State Standards, an initiative that elementary and high schools across the country will implement next year. The idea is to integrate more devices that support core curricula, such as English and math.

Common Core’s standards include technological development for the schools, teachers and students—from basic Internet/connectivity infrastructure (such as routers and switches) and teacher training to devices and dedicated software. For example, one Arizona school uses Cisco’s telepresence technology to offer an AP calculus class across 10 schools that they individually wouldn’t have been able to offer.

A Matter Of Resources

Ben Coleman, an eighth-grade math teacher in Fall River, Mass., assigns coursework using Android tablets. Reaction has been very positive, he says, primarily because the devices offer a new way for students to learn. Sounds promising, but here’s the dilemma: In Coleman’s low-income school system, students can’t afford the tablets. And the district can’t supply them for everyone.

The major barrier standing in the way of the connected classroom appears to be the same obstacle that has stymied every other educational initiative: resources.

Like many teachers, Coleman turned to DonorsChoose.org to raise money for the devices, but that didn’t provide enough to cover all of his students. “We have to do some collaborative exercises, as I only have 10 tablets for 24 students,” he said. “Usually I design exercises that are short, so that every student has an opportunity to use the tablet in each class.”

The Pew survey mentioned earlier underscores this dilemma. In the same poll, 56% of the teachers of the lowest income students said it is a major obstacle to incorporating more digital tools in their classrooms. Meanwhile, just 21 percent of the teachers of the highest income students felt the same way.

It seems many schools can’t get the resources they need to provide the fundamental digital tools and online education, much less advanced features, services and student data analysis that could power the next evolution of K-12 education. In other words, when it comes to the connected classroom, there’s still a disconnect.

But advocates clearly aren’t giving up. They continue to explore ways to improve the learning environment, and they see consumer and data-driven technologies as the way forward. These may be crucial steps in the advancement of primary and secondary education, as they set out on a path that—hopefully—all schools will have the ability to follow.

Lead image by flickingerbrad, school bus by bsabarnowl via Flickr