ReadWriteDrive is an ongoing series covering the future of transportation.

Imagine your car’s entire windshield working like Google Glass. Instead of peering through dust and grime to see the boring real world of traffic, you would see cars and key road features deeply integrated with data—colorfully highlighted and annotated for greater safety, convenience and enjoyment.

Does it sound far-fetched to have images and data projected on your windshield and rendered in 3D? Not according to Jules White, assistant professor of electric engineering and computer science at Vanderbilt University. “I think the Minority Report stuff is at least a decade away,” said White. “But we’ll see a lot of useful things in the near term.”

White served as guest editor for the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers’ February 2014 Proceedings of the IEEE, focusing on augmented reality on windshields. The project produced a set of eight peer-reviewed papers on the topic, including “Behind the Glass: Driver Challenges and Opportunities for AR Automotive Applications,” an overview of the nascent field.

Where The Rubber Meets the Web

White broadly defines augmented reality as the fusing of virtual information with actual objects in the real world. We’ve already seen the first example in today’s cars, in the form of dashboard monitors used with backup cameras.

When the car is in reverse, the driver not only sees a video feed from the level of the rear bumper, also a transposed set of color-coded lines indicating your distance from the other guy’s bumper you are about to dent. In addition, dynamic guidelines show where the vehicle is headed based on the position of the steering wheel. It’s a cheater’s guide to parallel parking.

Heads-up displays, available on some luxury vehicles, already use a small part of the windscreen to show basics such as speed and turn-by-turn directions. But that’s just the beginning.

In the future, approaching hazards—like a truck broken down in the middle of the road ahead, or a drunk driver weaving between lanes—could be highlighted with colors, or shaded to stand out, directly on the driver’s view through the windshield. The driver’s eyes can stay on the road when getting directions, rather than glancing to the center-mounted navigation system.

When driving at night, cameras and sensors working in conjunction with AR could make the road contours, signage and pedestrians more visible. Laser sensors and radars might one day allow drivers to literally look up and see around the corner.

Distraction in Overdrive

Of course, there are major user interface considerations about the best use of colors, gradients and layouts. (The auto industry has traditionally lagged behind consumer electronics and web in sophisticated interface design.) “There are all kinds of challenges,” said White.

One of the biggest concerns is over-reach of the new technology. “Anything that gives you the ability to make good decisions while driving should show up,” said White. “Anything that adds distraction is not the best idea.”

The authors of “Behind the Glass” anticipate the emergence of what they call “the social car.” In this scenario, layers of digital information about places and people in a city could be transposed on the windshield. While potentially cool, this could lead to driver distraction.

“We need to make sure that AR doesn’t become the next texting while driving,” said White. “The social display says that Paris Hilton just drove by. Are you going to have an accident that you otherwise wouldn’t have?”

Log Off and Drive

And there are technology challenges to ensure that drivers of every shape and size see exactly the same imagery, no matter where they are positioned in the driver’s seat. There is zero room for error. One of a myriad of technical decisions is whether to use 3D stereoscopic displays or flat one-level presentations.

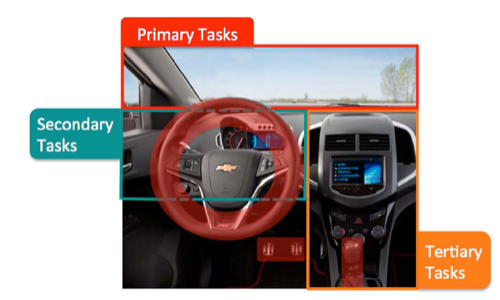

Adding to the complexity is that various technology and design strategies have to be applied to different types of interactions—from primary tasks such as way finding and control of speed; to secondary tasks such as using turn signals and windshield wipers; and tertiary tasks such as air-conditioning and infotainment. Which tasks should be displayed via Grand Theft Windshield—and which ones should remain analog and integrated on the dashboard or steering wheel?

While White and the other researchers see a lot of potential, driver tasks supported by AR will remain simple for some time. “A joint strike fighter aircraft has $250,000 sophisticated display helmets for the pilots. Precise data is required if you are a pilot of a high-performance attack jet,” he said. “That use case just isn’t there for automobiles.”