This post first appeared on the Ferenstein Wire, a syndicated news service. Publishing partners may edit posts. For inquiries, please email author and publisher Gregory Ferenstein.

A year ago, Sean Parker, the technology billionaire behind Napster, Facebook, and Spotify, invested several million dollars into a risky stealth startup, Brigade, which has the ambitious aim of increasing mass civic participation.

“The grandiose vision is to repair democracy; to do that, we have to fix political engagement,” Parker tells me.

He takes comfort in the fact that Brigade’s wide-eyed goal “is a little bit more achievable than it may seem at first blush, because turnout is so low, the average American is so disengaged, that even a few marginal changes — a few percentage points one way or the other — has a huge impact.”

Parker, and the driving force of Brigade, CEO Matt Mahan, think they can inject interest into America’s otherwise lukewarm political sphere by creating the next great social network around citizens’ civic life. That is, just as Facebook exists for our social lives and Linkedin for business, Brigade aspires to become a significant part of democracy’s 21st century infrastructure.

Civic identity, explains Mahan, “really does come down to, ‘what do you believe and care about?’ and “what have you done about those things?’”

But, for now, Mahan, Parker, and the Brigade team are starting very (very) small with a simple discussion tool that allows users to share and debate their political beliefs.

Eventually users will be able to take grassroots actions (like organizing votes or calling congressmen).

It may seem like an oddly barebones approach to such a big problem. Like the original Facebook, Mahan and Parker are betting that a sophisticated social network grows from a “fun” and “snackable” set of viral features — to use their terminology. Facebook won over the Internet with our penchant for sharing photos; Brigade is hitching a ride on our compulsive need to express our political opinions.

I showed off an early version of Brigade to Michael Slaby, chief innovation officer for Barack Obama’s 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns. He was tentatively optimistic.

“As a tool for grassroots action, a network of like-minded people bound together — as long as they have tools to interact and do things — can be incredibly powerful,” Slaby told me.

So, how does Brigade actually work? Beta invites will go out this summer. (Sign up here.)

Taking Positions

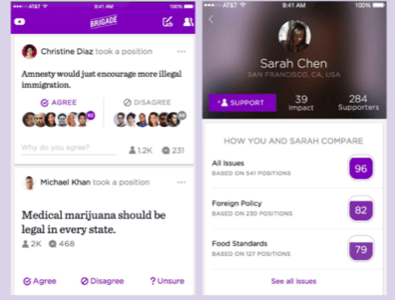

The app itself is deceptively simple: the front page of the app is a newsfeed-like vertical scroll of topic issues. For each topic, I can mark “agree”, “disagree” or “unsure” — then I get feedback on how my beliefs compare to my friends and to the wider population of users.

In the screenshot on the left, I can see who agrees with me after I select my opinion. On the right, I can dig deeper into how I compare to my friends and followers.

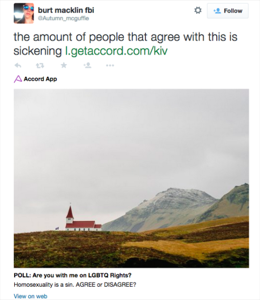

Despite being a modest conversation tool, its initial users nonetheless show healthy engagement. The company secretly tested their app under a stealth name, Accord. Twitter is full of people posting their Accord beliefs to their followers.

“We wanted to go for an immediate visceral reaction to whether this is someone who does think like me or doesn’t think like me,” explained James Windon, Brigade’s president.

Users can also make their own survey questions, create groups of followers around similar issues, comment on hot topics, and even receive an alert when a friend changes their mind on an issue (potentially providing a measure of which friends are most “influential” in their network).

That’s it for now: pretty simple.

Optimism, American History, And A Graveyard of Failures

Brigade is just one app in a long line of failed companies that have attempted to boost civic engagement. Few people might care, if weren’t for the fact that Brigade’s investor and visionary is a politically active billionaire who has seen the rise of three massive networks (Napster, Facebook, and Spotify).

See also: Charge Of The Tech Brigade

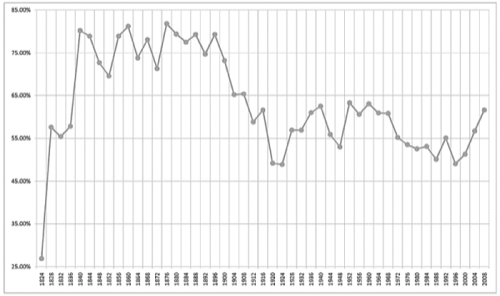

“This is a space that’s littered with failure,” acknowledges Parker, who combined two previously semi-failed civic startups, Votizen and Causes, to create the Brigade team. Parker’s north star is that America once had arguably the most active democracy on earth, with voter turnout in presidential elections consistently above 80% in the post-civil war Gilded Age.

According to historian Lawrence Kornbluh, Americans stopped voting after the country’s population exploded and a technocratic bureaucracy was needed to manage the growing assortment of complex national issues. No longer was politics something that was apart of everyday life; so, citizens just tuned out.

“Why hasn’t social media led to a revolution in political engagement?” asks Parker in an exasperated rant.

“We’ve gotten to a point where the population is much larger than we could have anticipated during the founding of the country and where the issues are more complex. So in order to create a better informed citizenry, we need to create better tools.”

To someone with a hammer, everything seems like a nail; to an Internet entrepreneur, every group of people looks like an unconnected network. Brigade is building the first mass database on beliefs.

Perhaps even better, the company can tie user’s opinions to their actual voting habits, since they have access to a clean version of the much-coveted “voter roll,” a tool typically limited to the arsenals of wealthy political campaigns.

“Beyond Facebook likes, the data set that Brigade is collecting doesn’t exist,” says Sina Khannifar, a consultant for the Electronic Frontier Foundation who has spearheaded two successful campaigns related to NSA spying and consumer cell phones rights.

Normally, Khannifar would have to manually construct a network of likeminded activists for each campaign, so Brigade’s database would potentially make online movements easier to get off the ground.

“I think that’s part of what’s exciting about Brigade from an opportunity perspective, because of the asset they’re starting with and the people involved,” concludes Slaby, Obama’s campaign tech leader. “That also raises expectations, which they’re going to constantly be trying to tamp down — but such is life.”

For more stories, subscribe to the Ferenstein Wire newsletter here.