The case pitting Google against Oracle over the use of Java in Android is turning into a spat of epic proportions. The opening arguments are in the books, with Google trying to portray Oracle as a spurned girlfriend trying to wrangle money out of a failed relationship. Oracle, meanwhile, painted Google as a callous ex-boyfriend who blithely takes what it wants, when it wants, with no regard for anyone else.

“It’s not about them protecting their intellectual property. It’s not about protecting the Java community,” Google attorney Robert Van Nest said. “They want to share in Google’s success with Android even though they had nothing to do with Android.”

“You can’t just step on someone’s intellectual property because you have a good business reason for it,” said Michael Jacobs, Oracle’s attorney. “Google makes a lot of money from Android, and a portion of that money is Oracle’s.“

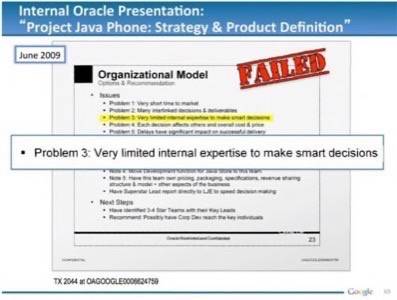

Oracle considered purchasing either Palm and its webOS software (which eventually got snapped up by Hewlett-Packard, with disastrous results) or Research In Motion and its BlackBerry platform. Clearly, Oracle wanted in on the smartphone game. Its biggest chip was Java, and Oracle seems to believe that Google stole that opportunity.

To see what’s really going on, let’s break down the case for each side with slides from the opening arguments:

Google’s Case

The first thing to know about the case is that it is currently in Phase 1, which will deal with Oracle’s copyright claims over Google’s use of Java in Android. Phase 2 will be about two specific patents that Oracle claims Google violated in creating Android. Phase 3 will be to determine damages, if any.

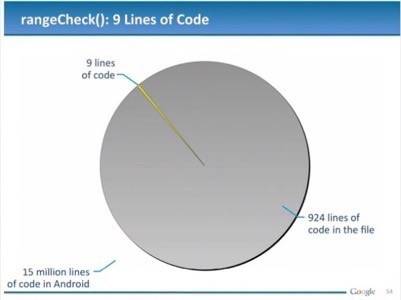

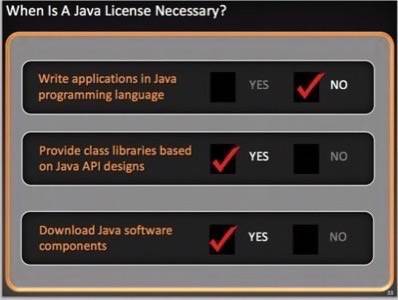

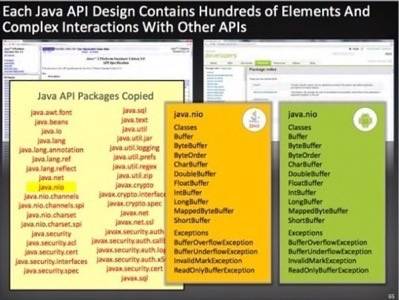

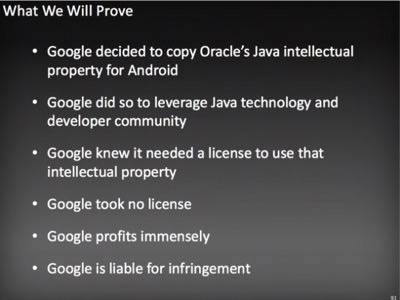

Google’s primary point is that Java was made free and open to the world by Sun Microsystems before it was acquired by Oracle. Countering, Oracle says that specific lines of source code were directly copied from Java, as were many of the APIs that make Java work. Oracle shows several instances of where Java code was copied in Android, which amounts to about nine lines of code.

Android has more than 15 million lines of code. Google says that it took three years and countless hours to put together Android and that everything it did was built from scratch in a “clean room” environment where developers were supposed to not have knowledge of existing outside technology.

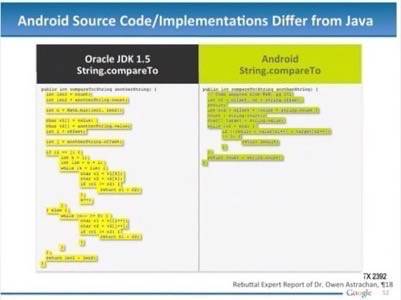

Oracle counters, saying that several of the APIs used in Android are directly named after Java APIs and perform the exact same function. Google shows that while the naming may have been the same, the code was distinctly different.

Google then goes on to play up the spurned girlfriend idea, showing how both Sun Microsystems and later Oracle welcomed Google to the Java ecosystem with its triumphant creation of Android.

Oracle’s Case

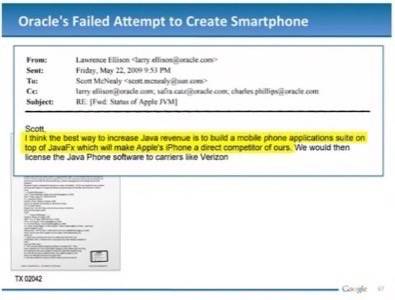

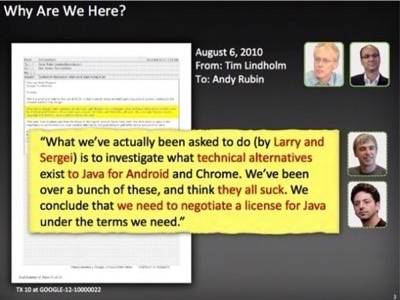

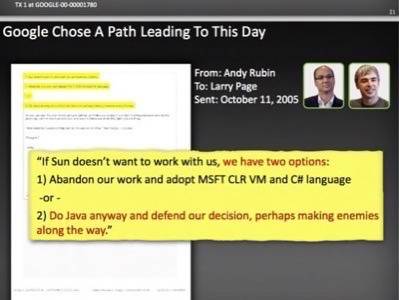

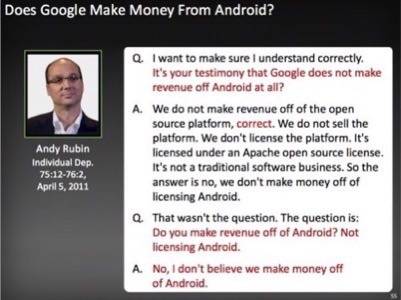

Oracle is trying to show that Google has fragmented the Java ecosystem and did not have the good of Java in mind when it created Android. Oracle’s lawyers are trotting out several emails between Google engineer Tim Lindholm and Android’s chief Andy Rubin saying, “we need to negotiate a license for Java under the terms we need.” Lindholm will be a witness early in the proceedings.

Oracle acquired Sun Microsystems in 2010 for $7.38 billion, mostly so it could take over control of Java.

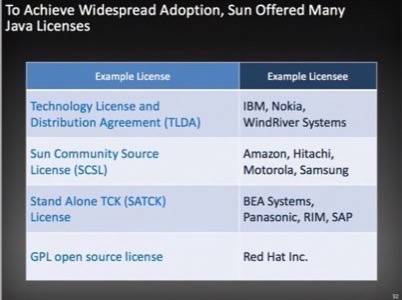

Oracle argues that many companies using Java accepted licenses from Sun, but Google spurned the licenses and did it itself, Sun (and later Oracle) be damned.

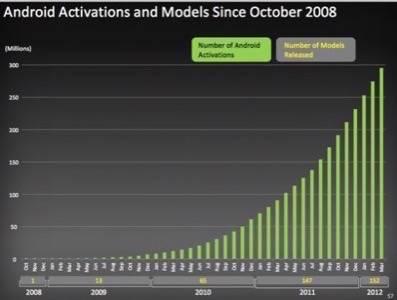

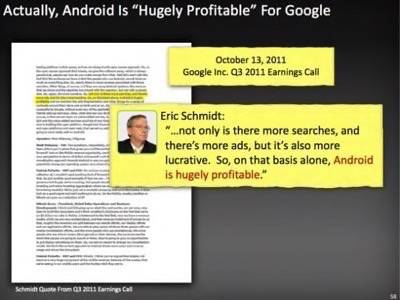

Oracle goes on to say that even though Google said internally that it thought it would need a Java license, it never got one. Because Google went ahead with Java without the license (ostensibly thinking it could do it all itself), Android has become “hugely profitable” for Google.

This is not necessarily the case. Google profits from Android through advertising and search, which are not necessarily a direct manifestation of Java itself. Google does not charge for licenses for Android and provides the source code and Linux kernel the operating system is built upon for free.

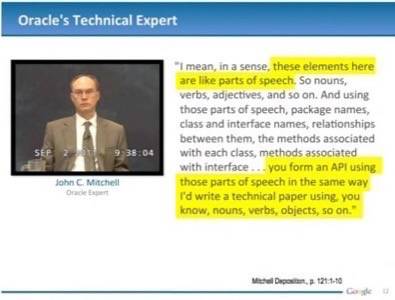

As mentioned, Oracle shows where Google copied certain elements of Java, such as source code, Java APIs and various objects and methods. This gets into the heart of the point in contention and will be where the jury must decide how much Google used, what it is worth and if it is even copyrightable.

Lead image courtesy of ImageStock