What would you do if you heard a giant boom and you didn’t know where it came from? If you’re like thousands of people in Portland, Oregon, you might hit Twitter and Google Maps to participate in the city-wide exploration of a slightly frightening mystery. Last night at about 8 p.m., people in a big part of the city felt their windows shake and no one could tell them what caused it.

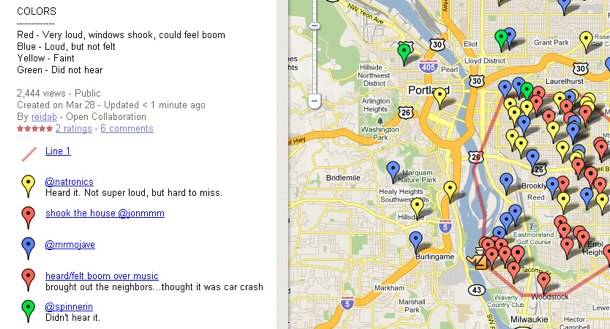

Was it a sonic boom? An angry deity? Even the mayor himself tweeted this morning that he was looking into the sound. In the meantime, thousands of people were using the hashtag #pdxboom and adding themselves to a hastily configured Google Map showing where they lived and how loud the boom had been there. In just a few hours, a pattern emerged, with reports clustering around one city park. This morning the police found a detonated pipe bomb there and cited the Google Map in their announcement.

Pausing the Stream

Reid Beels is a designer, geo-developer and one of the community organizers of Portland’s forthcoming conference Open Source Bridge (“The conference for open source citizens”).

Beels says he was sitting in a restaurant in southeast Portland when he heard the boom, and saw tweets streaming in about it within minutes. He searched Twitter for “boom” and “explosion,” limiting the results by location. Within five minutes, he says, a hashtag had emerged: #pdxboom.

What was the #pdxboom, people wanted to know? Some people said it sounded like thunder. Lots of people said it sounded like an empty trash Dumpster crashing on the ground. They mentioned their locations in their Tweets and Beels quickly grew frustrated that all this data was just streaming into the ether, lost from analysis.

So he threw up a Google Map with instructions to put a pin in your location and describe how the boom sounded to you.

Within an hour 100 people had placed pins on the map. Beels and developer Audrey Eschright came up with a color coded system to describe the intensity of the sound, and began retroactively coloring in pins based on any comments people left.

Then they found out that Google Maps will only display the 200 most recent pins placed in a public map. Beels’ friend Aaron Parecki wrote a script to download the map’s data every fifteen minutes. That came in handy when a few hours later someone vandalized the map by dragging a large number of markers outside the town. It was trivial to roll back to the last valid data.

The local TV news and the newspaper ran stories about the boom, and pointed their audiences to the Google Map. Thousands of people visited it, and just under 1,000 added a pin marking where they where and how loud the boom had sounded to them.

It became clear that the boom originated near the Sellwood Bridge; a big cluster of red markers surrounded the area, especially to the east. Thousands of people are still streaming in to look at the map; at the end of the day it’s now approaching 70,000 views, even if the mystery, if not the crime, is solved.

Some people thought it was a precursor Earthquake Boom. (I woke up convinced my house was in an earthquake.) But the Portland police went to a park in the area most filled with red flags on the map and found a large detonated pipe bomb. A Portland police spokesperson said the maps and tweets were very helpful.

A topographic view of the map made some inclined to believe that cliffs across the river and low-hanging clouds combined to make the sound travel as far across the city and in the direction that it did.

That Was a Practice Run

Beels says two big lessons came out of the experience for him. First, the tools they used were easy and fast, but they were also quite limited. Google Maps in particular was capable of multi-user collaboration but did poorly when it came to displaying a large amount of data. As Eschright wrote after the action, “It’s not the best platform for a couple hundred people, many without prior experience editing maps, to be using all at once.”

Inspired by campaigns like CrisisCampPDX and the CrisisWiki, Beels says the community is interested in setting up an installation of open-source, crisis support software Ushahidi on standby in case a real crisis has to be dealt with.

Beels says he’s inspired not just by what was done in this situation, but by what it revealed about the future. “The community of people who will search for things online and go out of their way to try to figure out what’s going on,” he says, “is larger than you might think.”

Marshall Kirkpatrick is leading a webinar for Poynter’s News University on Thursday about how location services are changing the news.