Augmented reality (or AR) is fast becoming as ubiquitous a term as “Web 2.0.” The field is getting noisier by the day, and AR as a field of research now has to co-exist with its status as an industry buzzword. Knowing the difference between the two is important. To do that, we have to examine the field and then revisit the buzzword you may have heard 10 years ago.

What Is Augmented Reality?

Augmented reality is a human interface for information that uses spherical coordinate systems to display information relative to the position of the viewer. Its most common application today is the overlay of information on the viewfinder of digital cameras. This is already a feature in many mid-point to high-end digital cameras that overlay the position of faces on the screen.

There are currently two distinct methods of augmented reality: marker-based and gravimetric.

Gravimetric Augmented Reality

Gravimetric AR uses data from a gravimeter to calculate the precise positioning and angle of a display device to determine the center, orientation, and range of a spherical coordinate system.

The first platform that was capable of delivering gravimetric AR applications on mobile phones was the Open Handset Alliance’s Android operating system running on the HTC Dream (better known as the TMobile G1).

One of those applications is Mobilizy’s Wikitude, which overlay’s Wikipedia data over the mobile phone’s camera view. Point the phone’s camera lens at the Golden Gate Bridge, for example, and see information overlaid on it. Move the phone around to find things on the bridge that you may not have noticed before.

Marker-Based Augmented Reality

Marker-based AR uses a camera and a visual marker known as a fiducial to determine the center, orientation, and range of its spherical coordinate system.

Hosted by the University of Washington, ARToolkit is the first fully-featured toolkit for marker-based AR. It is freely available under the GPL open-source license for personal use. ARToolworks Inc. is the commercial licensor of the platform.

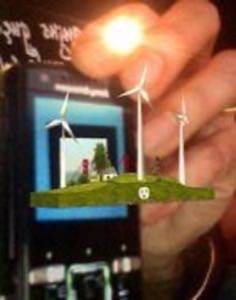

The most popular marker-based AR applications use the FLARToolKit, a descendant of ARToolkit, which uses Flash to overlay information on video from a computer’s webcam when a fiducial marker is visible.

Among the most recent implementations of this method is GE’s Smart Grid information website, where readers can print out a fiducial marker and hold it within range of their webcam. The screen then displays an interactive 3-D model.

The iPhone’s World

At the iPhone’s launch in 2007, John Doerr, Partner at Kleiner Perkins, joined Steve Jobs on stage. Speaking of this technology’s potential, he said, “Think about it: in your pocket you have something that is broadband and connected all the time. It’s personal; it knows who you are and where you are. That’s a big deal, a really big deal. It’s bigger than the personal computer.”

Over the past two years, we have seen the iPhone seed an entirely new field of mobile-connected experiences, with many mobile applications and competing platforms.

Because AR uses a spherical coordinate system to display data, it needs to know not just the orientation of the device but the direction in which the camera is pointing. To do this, it needs an accelerometer capable of gravimetry — or, simply put, it needs a compass.

The iPhone 3GS is the only iPhone that can run gravimetric AR applications. ARKit, an open-source toolkit for creating AR applications on the iPhone 3GS, was just created and released at iPhoneDevCamp last weekend. Apple alerted its developers last week that AR applications will not be available in its App Store until September. The Palm Pre does not have a compass, and the BlackBerry Storm has no AR apps. So, for now, Android phones are the only mobile gravimetric AR devices in the wild.

Augmented Reality and Ambient Intelligence

Ambient intelligence is a human interface metaphor. It implies that the connected devices around us are all connected to some form of intelligence. We see this when we drive through an automated toll system like FasTrak on the Golden Gate Bridge. Using the RFID tag issued by the bridge authority, the bridge knows who we are and what to do. We don’t have to actively submit intelligence of our own: the ambient intelligence takes care of the job.

Globally positioned data is so voluminous that not all of it can be displayed. That fact combined with the bandwidth limitations of mobile carriers creates quite a challenge for the industry: deliver the data that is relevant to the user and location, and before the user gets there.

The holy grail of the mobile AR industry is to find a way to deliver the right information to a user before the user needs it, and without the user having to search for it. This holy grail is likely in a ditch somewhere beside a well-traveled road in the district of the semantic Web, ambient intelligence and the Internet of things. Be wary of any hyped-up invitation to invest in a company that claims to have gotten the opportunity right. What we’ve seen in the commercial industry to date is a rather complex version of a keyboard, mouse, and monitor.

Guest author: Sid Gabriel Hubbard is a blogger, Internet entrepreneur and three-time CTO. He leads the Android Maker’s group in San Francisco and the Bay Area Augmented Reality Meetup Group and is a contributing member of the iPhone ARKit open-source project.