The timer in the built-in Clock app on the iPhone sucks, so David Barnard built a new one, Timer. But if you search for “timer” in the App Store, you won’t find it. Because of Apple’s obscure, ever-shifting search method, making the best timer in the store is not enough.

Barnard invested $7,000 to build this app. It’s the best timer iOS could ask for. Instead of a fiddly, spinning wheel, it has giant buttons that represent preset periods of time. All you have to do to start a timer is tap the interval you want. To set a new one on the fly, you dial it in with the full-sized phone keypad. It’s fast, smooth, easy on the eyes, and it costs a buck.

More than a month into its tenure on the App Store’s shelf, though, the app has only made about $5,000, not even covering expenses yet. Why aren’t iPhone users downloading it by the thousands? Because they can’t find it. In a search for “timer,” this app barely makes the top 50.

“Apple has a huge discovery nightmare on their hands,” Barnard says. “Trying to get people the best app is a nightmare.” The problem is that search results are inconsistent, and they change constantly as Apple tweaks its algorithm. Indie developers such as Barnard, who stake their livelihoods on Apple’s App Store, are left in the dark.

Life in the App Store

Barnard founded App Cubby in March 2008. He’s been developing iPhone apps since before there was an App Store. His experience bringing apps to market is extensive, with plenty of mistakes to learn from, and he knows good people on all sides of the industry, indie and Apple alike.

He decided to build Timer as a quick project using this wealth of experience, and it seemed like a slam dunk.

He needed timers constantly – grilling, making coffee, putting his 3-year-old in time out – and he got tired of spinning the Clock app’s cumbersome wheel. He measured twice, cut once and shipped a grade-A timer app pretty close to his estimated development cost.

Timer launched with good press, too. It’s a simple, one-trick app, but it meets a common need beautifully. The built-in timer doesn’t, and neither do the 30 – thirty – third-party timers Barnard tried before he built his own.

So what went wrong? Apple changed the rules. The search tricks he learned from other apps suddenly stopped working. “The App Store is a complete black box,” Barnard says. “How do you intelligently and thoughtfully run a business in this black box?” Despite being in the game for four years and knowing all the key players, “I still feel so helpless most of the time,” he says.

Building for Search

“Sustainability in the App Store – especially for niche apps – is all about search,” Barnard says. “Over time, I have [search]-optimized my apps.” This might bring to mind shady, black-hat tactics. Some developers do abuse the ability to game App Store search results. But Barnard is fastidious in drawing a distinction between community-minded and bare-knuckle practices.

He has seen the dark side of App Store search spamming first-hand. Intuit used to make a mileage tracking app called Tap2Track (now defunct), a competitor with App Cubby’s Trip Cubby. At one point, Intuit put the word “cubby” into the app’s information so people searching for Barnard’s app would find it.

Barnard has used keywords to make his apps discoverable, and Timer is no exception. When you’re bombarded on all sides by competitors trying to get an edge, you have to defend yourself. But he would never put his competitor’s name in as a keyword. This is just the only way to build a business. “That’s crossing the line,” he says.

As an indie developer, Barnard has a reputation to uphold. He’s known for his frankness and transparency about his business. His blog post about building Timer attests to that. He’s up-front about optimizing his apps for search, but he only goes as far as he has to.

“My intentions with Timer are a good example of playing within the current rules to give people something better,” he says. “I think there’s honor in taking the high road, but when you’ve got kids to feed and you’re running a business, you have to try to optimize.”

Barnard was scratching his own itch by building this app, but it only made financial sense if he could get it in front of people. Using tactics he learned building his other apps, he optimized Timer for discovery via App Store search. It worked for a little while, until, suddenly, it didn’t.

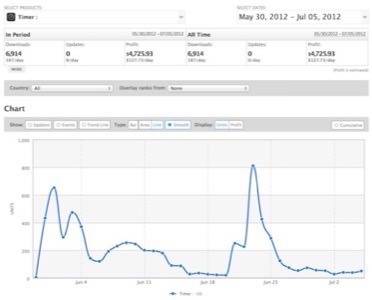

Barnard shared this chart of Timer’s performance with ReadWriteWeb. After the launch frenzy, a feature by Apple, and a week or so of strong downloads, purchases dropped off. The second spike came from a review on The Unofficial Apple Weblog, which drove far more traffic than natural discovery has.

On June 21, App Cubby launched Launch Center Pro, its flagship app, and cross-promotion of Timer inside that app has sustained some of the sales. Otherwise, the chart would have gone even lower.

Launch Center Pro sponsored the July 6 episode of The Talk Show, driving a bunch of downloads of that app, thus helping Timer as well. As of Tuesday, App Cubby’s Timer is still #49 in search for “timer,” despite 7,500 downloads, a nearly perfect rating, and being featured by Apple. It’s not that the timers (and nontimers) above it are better; they’ve just been in the store for longer.

Shifting Sands of Search

Steve Streza, lead platform developer at Pocket, has also been grappling with making apps discoverable in a crowded market. Pocket used to be called Read It Later, and there’s no exact science for making major changes like that in the App Store.

Streza has noticed pronounced changes in App Store search results during recent weeks, but they’ve had the opposite effect on Pocket. Instead of getting buried, Pocket has gone from about No. 30 to the very top of the list for searches for “pocket.”

Why does Pocket do so well while Timer does so poorly? There’s no way to know, but Pocket has been around for a long time – taking the earlier name into account – and based on Barnard’s experience and Streza’s experiments, long-term reputation seems to play a bigger role in search results lately.

Developers used to load their app descriptions with keywords. That tactic doesn’t seem to be working anymore. Apple stopped looking at app descriptions for keywords “in ’08 or ’09,” Barnard says, making titles the only choice for search optimization. Streza says that search seems to be taking new factors into account. It’s not just terms anymore, but overall downloads and usage.

Barnard’s experience corroborates this. His longstanding apps, Gas Cubby, Trip Cubby and Mirror, have not slipped in the rankings like Timer has, though he has built his App Store strategies using all of them.

Streza draws a contrast between life for developers before and after the App Store. “Techniques for tweaking and [search-optimizing] came from Mac culture,” Streza says. “Google was what mattered then.” Developers used search engine optimization (SEO) so that anyone could find them on the wide-open Web.

But the same kinds of approaches don’t work within the pruned hedges of the App Store. “You don’t have as much freedom to make your own rules in terms of how you reach the customer,” Streza says. “You’re playing by Apple’s rules.”

“I haven’t gotten the impression that [Apple was] tweaking [search] very much until recently,” Streza says. “And not all of [the changes] are working out for the developers that should be benefitting from this.”

Streza’s impression seems to be dead on. As initially reported by TechCrunch and measured by Ian Sefferman at MobileDevHQ on June 25, keywords suddenly matter less, and overall downloads matter more across the board.

“The [app] name hack is definitely a hack, and I can totally understand why Apple is disincentivizing that,” Barnard says. But instead of keywords and names, Apple now seems to be emphasizing reputations. The catch–22 is that a new app has no reputation. “It really disincentivizes people taking risks on new apps,” Barnard says. “What’s the next app I’m going to build that I’m hoping will be able to sustain sales?”

To test the new search criteria, Streza suggests a search for “insta,” a prefix common to at least three major iOS apps, Instacast, Instagram and Instapaper. They’re buried under other, obscure apps with no clear common theme. But search for “photo” today, and Instagram shoots to the top of the list.

At this point, it would be crazy to try to unseat Instagram in the App Store search for “photo.” But if long-term reputation is an essential part of search, a crazy newcomer would have no hope of succeeding.

Apple’s Way Out

Long-term reputation is a sensible filter for App Store search. You wouldn’t want to drive a ton of downloads for unproven apps. The problem is that the App Store’s built-in discovery mechanisms are too blunt for new, great apps like Timer.

In February, Apple bought Chomp, a search engine for mobile apps that fine-tuned results with a proprietary algorithm that “learns the functions and topics of apps.” Apple hasn’t released any substantial information about the acquisition, and it won’t comment on future plans. But based on what we know about the upcoming iOS 6 (and what isn’t under NDA), discovery in App Store looks like it will be pretty much the same as it is today.

Streza’s hunch is that the discovery interface is untouched because a bigger release is coming, something more “Chomp-like,” but we can’t see it yet.

In the long term, Apple and its indie developers have the same interests at heart. They both want a huge, profitable platform that lasts for years and years. But Apple has chosen secrecy and careful timing as its strategy. Without a clear sense of direction, developers just have to keep guessing.

In the meantime, small app shops such as App Cubby rely on strategies outside the App Store, like big ad buys on blogs or podcasts. But even that is fraught with problems. “I can’t even effectively measure my returns,” Barnard says. “Apple provides zero insight into where traffic is coming from. There’s a lot that we can do outside of the App Store, but every experiment I’ve done in paying for advertising, I end up losing money as far as I can tell.”

It feels like spending good money after bad trying to climb the App Store charts, he says. It’s a prohibitively costly way to drive sales of something that brings the developer $0.70 a pop.

“If this were the Web, if this were a restaurant, there are so many different tools and business models and options for running your business and figuring out what the hell is going on,” Barnard says. In the App Store, “we have no clue.”