Apple has yanked the controversial game SweatshopHD from its App Store — a move rife with irony given Apple’s own long association with questionable labor practices in China.

Apple actually pulled Sweatshop last month, although the news just broke Thursday on the game site Polygon. The game put players in a managerial position at an expanding offshore clothing factory. Among other things, it offers the option to employ cheap child labor as everything from fires, longer work hours, and mutilating injuries force players to make increasingly dark decisions to meet the bottom line.

Simon Parkin, head of the game’s studio Littleloud, told Polygon the title was pulled because Apple was “uncomfortable selling a game based around the theme of running a sweatshop.” The game was originally released for browsers in 2011 and saw an iOS release last year.

This Is Not The Exploitation You Think It Is

But Sweatshop wasn’t designed to make a quick buck off a cartoony rendition of offshore manufacturing and child exploitation. Littleloud said it got fact-checking input from Labour Behind The Label, a UK-based charity that raises awareness about who manufacturers many Western branded products and where.

Sweatshop was also featured by Games For Change, a New York-based nonprofit that aims “to leverage entertainment and engagement for social good.” On its Web site, Littleloud says it set out to make a game that “challenged young people to think about the origin of the clothes we buy.” Its tag line for the game: “Explore the high cost of cheap fashion.”

Despite all that, Apple chickened out. It’s a telling move, mainly because Apple has long been fighting allegations of sitting idly by while its many Chinese manufactures employ a swath of unfair labor practices to meet the world’s demand for iPhones and iPads. Principally among that group is Foxconn, who just last fall admitted to using child labor with workers as young as 14, and has been routinely plagued by its high suicide rate and massive riots due to the company’s long work hours and robotic lifestyle regiment it imposes on its workers.

Playing Sweatshop: A Lesson In Cruelty

As I fired up the in-browser version of the game for the first time, I was met with a lengthy and darkly comic introduction that takes you from a store selling a Nike-esque shoe in high demand across the loading docks, delivery trucks, and ocean-crossing steam liners that move it from the sweatshop it was produced in. This is all to the soundtrack of unbelievably catchy arcade techno music that starkly contrasts with what you’re seeing on screen.

The game starts small, putting you in charge of one child laborer and $100 to hire more workers. Sweatshop is an optimization strategy game, meaning you’re given a top-down view of the factory and must accomplish a task as fast as possible, and with as few errors as you can manage, through furious mouse clicks and intense monitoring of the game’s multiple working parts, which in this game happen to be fearful children and exhausted adults.

The children are scared mostly because of the cruel and heartless head manager, a stocky, mustached man in a shirt and tie that continuously calls his workers “lazybones” and complains about having to provide them with water. As the conveyor belt pulls in material to make things like hats and shirts, you have to make sure each item is completed before it gets to the end of the belt or it counts as a failed item. If you rack up a certain number of failed items – like I did numerous times while trying to keep my workers hydrated and simultaneously maximizing my speed – you lose the contract and have to restart the level.

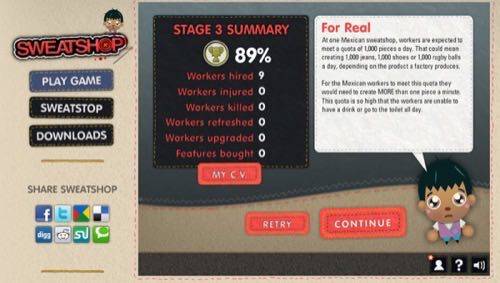

Sweatshop holds nothing back when it comes to making you reflect on your decisions, and ultimately begin to marginalize every worker until you begin to think of them as just another cog in the big manufacturing machine. The end of each level gives you a stat rundown, boosting your overall score for the level with bonuses for quality, time and the amount of cash used (which you can try to control by firing workers as they become less useful or by hiring more children). You’re also given a button at the bottom to check your CV, which displays the trophies you’ve earned for completing certain in-game milestones like refreshing your first tired worker.

While it haphazardly treats themes of child labor and deplorable working conditions in a satirically upbeat manner, Sweatshop also spends a good chunk of time addressing the player directly in a serious manner. At the end of each level, the game’s representative child laborer character offers a real sweatshop fact.

That same character engages in one-on-one conversation with you at the beginning of each level to let you know what makes for more manageable conditions, like paying for more water and keeping the conveyer on slow. The child even offers his personal story — for instance, how he wishes he could attend school but instead must work to support his family.

Why Apple Should Allow Socially Conscious Games

Many may note the irony at play in Apple banning a game over its controversial, child-labor-related content following Foxconn’s breaking of labor laws last year. Apple deserves some credit it acknowledging the problems of outsourced manufacturing; it launched an investigation last year into Foxconn’s labor practices (though only after the New York Times published some damning investigative reports).

But by banning Sweatshop — a game that, while unorthodox in its message delivery, does actively try to make smartphone users think about the welfare of the workers behind the things they wear and the devices they use — Apple has again retreated from the debate. Not exactly what you’d normally expect from a company that once exhorted people to “think different.”

Approving and promoting a game like Sweatshop might seem risky from a traditional PR perspective, but it would highlight Apple’s willingness to allow others transparent discussion of labor conditions on its platform. It would open up debate, and might even win the company some kudos among critics who have blasted Apple for its lackluster response and feeble efforts to improve working conditions at its overseas contractors.

At the moment, though, it seems Apple’s App Store nannies are too “uncomfortable” to take that chance.

How Alterna-Apple Could Redress The Problem

Imagine for a moment we lived in an alternative universe, one in which Apple executives really wanted to improve working conditions in iProduct factories. That’s exactly the world conjured up in a recent report by the Economic Policy Institute, a left-liberalish think tank, which argues that Apple could, and should, deploy its enormous cash reserves to pay higher wages to the Chinese workers who assemble its iPhones and iPads. (And, for good measure, to its Apple Store retail workers as well.)

“Almost entirely absent from the discussion has been whether those reserves should also be used to provide fairer compensation to the workers making its products abroad or selling its products here,” writes report author Isaac Shapiro.

Shapiro argues that Apple could take several simple steps to improve thousands of lives — for instance, by switching to a livable wage standard, providing retroactive compensation to workers for past labor rights violations, and to keep working to lower the 60 hour work weeks at many of its contractor factories.

Similarly, the EPI report calls for Apple to fulfill its March 2012 promise to compensate workers for all of their past unpaid hours. “Apple has since gone silent on this promise, and may be walking away from it, even though the promise is a response to illegal and unjust work practices, and could be fulfilled using just a tiny fraction of Apple’s massive reserve,” Shapiro writes.

These are, generally speaking, terrific suggestions for Apple. But if the iPhone maker doesn’t even have the cojones to allow a social advocacy game on its App Store, I sure wouldn’t hold my breath waiting for it to put some muscle behind the real-world issues that game addresses in virtual form.