ReadWriteBody is an ongoing series where ReadWrite covers networked fitness and the quantified self.

You know those super-awkward “before” shots with a fat guy holding a newspaper as he’s about to start a diet and workout regimen?

I have to imagine that’s what Apple’s software designers had in mind when they created the first version of the Health app that’s getting installed on millions of new and upgraded iPhones.

It’s easy to be critical of a 1.0 version of any piece of software. But this is Apple, which has set expectations around its push into health and fitness sky-high. If you’re going to put the bar all the way up there, you’d better be able to jump up, grab it, and knock out a solid pull-up. Chest to the bar.

A Sickly Debut

The challenge for Apple is that the Health app, by itself, doesn’t do anything. It’s dependent on other apps to feed it nutrition data, workout sessions, and vital signs via Apple’s HealthKit software, which developers build into their offerings.

We were supposed to start using Apple’s Health app weeks ago, when iOS 8 launched. But shortly after Apple rolled out its new mobile operating system for iPhones and iPads, it abruptly yanked health and fitness apps using its new HealthKit software from the App Store—and forced them to release new versions minus HealthKit.

A week later, we almost saw the debut of Health-compatible apps with iOS 8.0.1. Then Apple yanked 8.0.1. No HealthKit for you! Finally, with 8.0.2, wary Apple developers gingerly started rolling out HealthKit apps.

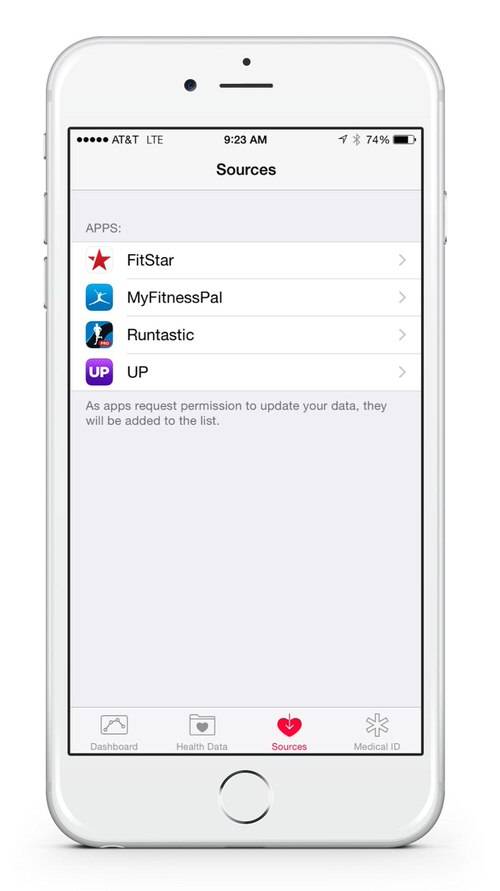

I was ready to go, with folders full of theoretically compatible apps, like FitStar, Jawbone Up, MyFitnessPal, and Runtastic. It was just a matter of hooking them all up to Health.

A Lot Of Tapping, Not Much Action

The result was underwhelming, to say the least.

Health has four tabs at the bottom: Dashboard, Health Data, Sources, and Medical ID.

Dashboard provides daily, weekly, monthly or annual views of your health statistics. Health Data provides list views and lets you control which data points appear on the Dashboard. Sources lists the apps you’ve connected to HealthKit. And Medical ID lets you create emergency medical information, like drug allergies, that’s displayed on your phone’s lock screen.

Because I have a new iPhone 6, which has a motion coprocessor to track steps, I can feed that data into both MyFitnessPal and Jawbone Up, and from there back into the Health app. But I’d already connected MyFitnessPal to the iPhone’s steps counter and hooked MyFitnessPal and Up together in the individual apps, so that wasn’t much of an improvement.

MyFitnessPal feeds my calorie intake into Health. But I could already see that data in MyFitnessPal. Not much of an improvement there. In theory, other apps can now pick up that data and provide analysis, but I don’t have any that make use of it.

FitStar and Runtastic add data about my workouts to Health. But I’d already connected these apps to MyFitnessPal, which tracks calories burned against my food intake in a way that’s more useful than the Health app’s charts.

And then there’s the Health app’s design. It’s not exactly ugly, but it’s not useful. The interface is confusing, and the app doesn’t provide any kind of interpretation for what I’m seeing, or suggestions on what to do differently in terms of my exercise or nutrition.

One of the most compelling features of HealthKit is the way it handles duplicate entries from multiple sources of data. But actually accessing this feature is tricky.

Paul Veugen, the cofounder of fitness-app maker Human, explained in a recent blog post how to use Health’s multiple-sources feature. You have to select a data type from either the Dashboard or the Health Data tab, tap on a “Share Data” button and then “Edit.” Like most Health functions, it’s completely nonintuitive. (Veugen’s cofounder, Renato Valdes Olmos, followed up with a number of useful suggestions on how to fix Health.)

For that, I’m better off using an app like Up, RunKeeper’s Breeze, or Human, all of which provide helpful tips on daily activities as well as simple data logging. Or MyFitnessPal, which many of my friends use, where I get real human feedback on little achievements like hitting my calorie goal for the day.

Health doesn’t have any of the behavioral or social features which are key to a fitness app’s success. There’s simply no reason to use it, except as a crude data-storage tool.

Before—And After?

Perhaps this is all by design: Rather than compete with fitness-app makers, Apple wants to work with all of them. A functional, useful Health app that might compete with them for attention doesn’t serve that goal.

But it seems maddening that Apple would hire dozens of health and fitness experts only to produce such a crippled, useless piece of software.

So for now, think of Health as a very simple interface on top of a database of health statistics. It’s not something for you to use. Instead, it’s a convenient way for the people who make actual useful fitness apps to share data.

It saves you from having to constantly reenter your weight, age, and other statistics, and it helps you avoid duplication of workout sessions and step counts. And for medical applications, it may find some niche uses—but even there, the utility is likely to come in specialty applications that swap data with Health rather than in the Health app itself.

Apple’s Health app, in its current incarnation, isn’t in very good shape. It could eventually become useful, but Apple will have to do a lot of work to get there—or buy a company like Human, Jawbone, RunKeeper, or MyFitnessPal to learn how to make fitness apps that people will actually use.

The best thing you can say about the Health app right now is that it makes for one heck of a “before” photo.

Photo by Shutterstock