The Platform is a regular column by mobile editor Dan Rowinski. Ubiquitous computing, ambient intelligence and pervasive networks are changing the way humans interact with everything.

The middle class of mobile app developers is completely non-existent.

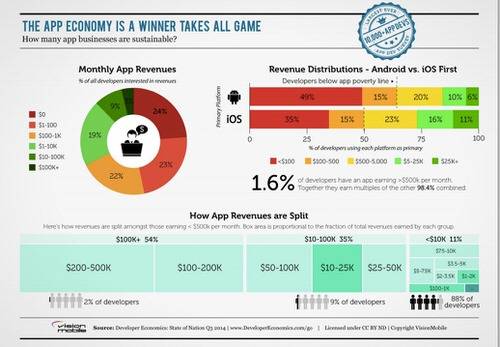

According to a research survey from market research firm VisionMobile, there are 2.9 million app developers in the world who have built about two million apps. Most of those app developers are making next to nothing in revenue while the very top of the market make nearly all the profits. Essentially, the app economy has become a mirror of Wall Street.

According to the survey: “The revenue distribution is so heavily skewed towards the top that just 1.6% of developers make multiples of the other 98.4% combined.”

About 47% of app developers make next to nothing. Nearly a quarter (24%) of app developers who are interested in making money from their apps are making nothing at all. About another quarter (23%) make less than $100 a month from each of their apps. Android is more heavily affected by this trend, with 49% of app developers making $100 or less a month compared to 35% for iOS.

As you can see, only 6% of Android developers and 11% of iOS developers make more than $25,000 per month, numbers that make it extremely hard to build a real, sustainable business with mobile apps.

If we chop off the top and the bottom of the market, that leaves a “middle class,” which is extremely poor, struggling to make any kind of money. About 22% of developers earn between $100 and $1000 a month off their mobile apps. The higher end of that scale isn’t bad for hobby developers, but professional app makers can’t get by on that. VisionMobile draws an “app poverty line” at apps that make less than $500 a month, leaving 69% of all app developers in this category.

That leaves a very thin middle class that makes between $1,000 and $10,000 a month per app. To put that in perspective, the American middle class at large earns between $40,000 and $95,000 annually (with the “middle-middle” making $35,000 and $53,000 per year).

So what happened to all the riches in the app economy? The fact is that the money dried up a long time ago and only the top of the food chain makes any real money. The developer middle class is small and struggling while two-thirds of developers trying to make money off their apps may just look towards other ways to employ their skills.

Vision Mobile concludes:

More than 50% of app businesses are not sustainable at current revenue levels, even if we exclude the part-time developers that don’t need to make any money to continue. A massive 60-70% may not be sustainable long term, since developers with in-demand skills will move on to more promising opportunities.

The Balloon Effect

The death of the developer middle class should come as no surprise to industry watchers. The app economy has mirrored the rest of the mobile industry of the last several years.

The first comers to the industry carved out names for themselves and benefited from the unexpected popularity of the smartphone (led by Apple’s iPhone and the App Store). Copycats and entrepreneurs raced to get in on the riches, creating a bloated app store filled with poor and mediocre apps to fill just about every product category you could think. This pushed out quality (but limited) market apps. The revenue consolidates at the top of the market

App store inventories continue to grow, one poor app after another. This will lead to the eventual realignment of the developer pool, building mobile apps as they struggle to find revenue or venture money to grow their businesses. In the past, I have called this the balloon effect. We’ve have seen it in smartphone manufacturing (where middle tier players like HTC get pushed out as Samsung and Apple dominate) and developer services where companies struggle to compete against each other and industry heavyweights. Eventually, these companies are either bought or merge. (StackMob and Parse were acquired, PlayHaven and Kontagent merged to become Upsight.)

The app economy is one of the foundational elements of the mobile industry, so the balloon effects take longer to manifest but the impact is much broader on the developer community.

The Sparrow In The Coal Mine

Developer David Barnard offers a cautionary tale about an app called Sparrow.

We’ve all read stories about and been enthralled by the idea of App Store millionaires. As the story goes… individual app developers are making money hand over fist in the App Store! And if you can just come up with a great app idea, you’ll be a millionaire in no time!

Sparrow was an app built by a three-person team which became five people after a venture capital seed round. It started as a paid app in the Mac App Store and then the iOS App Store, with plans for a Windows app on the way. Sparrow debuted well and had a couple popularity spikes with new releases and media coverage. But Sparrow was not long for the world. It could not sustain the popularity needed to make enough revenue for its team to make the riches its efforts may have deserved. Eventually Sparrow sold to Google—a quality outcome. But most developers will never see the same type of popularity spikes, venture capital investment or exit to a huge company experienced by Sparrow.

If a well received, well-made and popular app like Sparrow could not hack it in the mobile app business, the average indie developer has little chance to make a dent without stumbling upon a mega hit, a la Flappy Birds (developed by a lone programmer in Vietnam). The kicker is that Sparrow’s tale … is from 2012.

Two years later, the opportunities for apps like Sparrow have more or less dried up as thousands of apps have filled its category, making it harder for app publishers to stand out from the crowd. For every Instagram success story, there are thousands of apps that make little to no money and have no prospect of success in the near future.

Barnard summed it up well, diagnosing the prognosis of the app developer middle class in 2012.

Given the incredible progress and innovation we’ve seen in mobile apps over the past few years, I’m not sure we’re any worse off at a macro-economic level, but things have definitely changed and Sparrow is the proverbial canary in the coal mine. The age of selling software to users at a fixed, one-time price is coming to an end. It’s just not sustainable at the absurdly low prices users have come to expect. Sure, independent developers may scrap it out one app at a time, and some may even do quite well and be the exception to the rule, but I don’t think Sparrow would have sold-out if the team—and their investors—believed they could build a substantially profitable company on their own. The gold rush is well and truly over.

Top image courtesy of Flickr user Bennet.