It’s hard not to be impressed by the latest demonstration of Android, Google’s soon-to-be-released open-source mobile OS. While last100’s Dan Langendorf is reserving judgment, I’m already sold on Android’s User Interface. Of course, the biggest promise of Android isn’t its UI but its openness, and it’s here where comparisons to the iPhone are also inevitable. But Google is banking on one app that carriers and handset makers won’t want to touch – the browser.

Syndicated from last100, our digital lifestyle blog

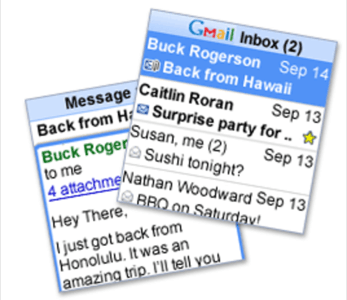

Android’s UI looks to have borrowed just enough from Apple’s iPhone, as well as some of the design Zen of the original Palm OS, to more than satisfy my needs. However, on the one hand Google wants us to believe that Android isn’t a direct response to Apple’s own offering (which, chronologically, may well be true), but at the same time is keen to remind developers that in contrast to the iPhone they won’t need to get Android applications certified by anyone, nor will there be any hidden APIs (application programming interfaces) accessible only to handset makers or mobile operators — another dig at Apple.

What Google is less keen to highlight, however, is how Android’s openness could potentially lead to the platform becoming fragmented, resulting in a mishmash of incompatible flavors or implementations. That’s because, notes The Register, Google plans on open sourcing Android “under a freewheelin’ Apache license” in which carriers and handset makers will be able to make any modifications they like. These could be as innocuous as cosmetic changes to the UI, such as replacing icons with the networks’ own branding, to something more significant like swapping which default applications and services are installed, including the option to remove Google’s own wares and, say, replace them with Yahoo’s or a carrier’s own.

“They can add to it. They can remove from it. They make it their own”, Android project leader Andy Rubin told attendees of last week’s Google I/O developer conference in San Francisco.

However, even if this means that handset makers and carriers can customize and control the ‘out of the box’ configuration of Android-based phones — since the platform is open, users should also have the same freedom to add to it, remove from it, and make it their own, right?

Not necessarily.

In theory there is nothing stopping any Android vendor, regardless of if they are a member of the so-called Open Handset Alliance or not, from locking down portions of the OS, even going as far as removing access to certain APIs. Rubin confirmed as much at the I/O conference, but attempted to reassure developers who are worried that their applications may face compatibility problems, by revealing that Google will provide tools to easily verify the make-up of each Android handset.

“We’re providing a piece of technology – I can’t go into a great amount of detail – that tests the APIs,” quotes The Register. “This will be a script that you’ll be able to run… and determine whether all the APIs are there.”

In other words, users may be faced with the situation of downloading and attempting to install applications on their ‘open handset’ only to be greeted with a message saying that their particular Android phone isn’t compatible.

Also see: Worries over Google phones: What if they’re just ordinary?

While this is probably painting a worse-case-scenario, the whole point of Android is that it is supposed to help address the current status quo in which “the mobile platform is unbelievably fragmented”, according to Vic Gundotra, Google’s vice president of engineering. So it’s somewhat surprising that the company would allow such a possibility in the first place.

Or is it?

How else could Google persuade carriers such as T-Mobile, Sprint and Telfornica, along with a host of incumbent handset makers to come on board in the form of the Open Handset Alliance?

Besides, Google is really banking on there being at least one application that the carriers and handset makers leave well alone, regardless of how else they tinker with the OS. And for Google’s purposes that application far exceeds the importance of any other, and offers the best hope of giving developers, including Google themselves, the unified mobile platform they crave.

That application is of course Android’s mobile Web browser, built on the same WebKit source code as Apple’s version of Safari for the iPhone. Nokia also utilizes WebKit in its own browser, albeit one built on older code.

Gundotra has already gone on record saying that the iPhone features “a better mobile browser than anyone had ever delivered before”, and that he expects others to follow Apple’s lead and adopt WebKit-based browsers of their own, helping to eliminate the need for developers to create separate versions of their web applications for each device — or at least if those apps stay in the browser.

All of which makes perfect business sense for the world’s largest Internet ad company.

“Google does reasonably well on the open Internet. We’d like that model to come to mobile phones,” says Gundotra.

Image credit: Android UI AndroidCommunity.com

This post is syndicated from last100, our digital lifestyle blog covering Internet TV, digital music, Mobile Web and more. You can subscribe to last100 here.