The craziest thing about a typical “top secret” U.S. Government phone is that you can probably spot it from a football field away. If your mental picture of a Hollywood-style NSA agent drives a black AMC Ambassador, wears a polyester suit and Ray-Bans, and smokes Luckies, then his phone may either be Maxwell Smart’s shoe or a General Dynamics Sectera Edge (pictured left). At any distance, it looks like one of the pocket football games my junior high school vice principal used to confiscate and collect in his back drawer.

The National Security Agency wants a real-world smartphone, not the one it has now – not the one you see here. Of course, it must fulfill the Dept. of Defense’s requirements for session encryption and data retention. But beyond that fact, the NSA wonders why its secure phone can’t have multitouch, apps, and speed just like the civilians have. Based on looks alone, you’d think the civilians are a couple of pegs ahead of the G-men. This is a story of looks being more deceptive than even a security agency could have anticipated.

Enter the Fishbowl

The real face of the National Security Agency looks more like Margaret Salter. At the RSA Conference in San Francisco last Wednesday, Salter told attendees the story of the NSA’s Secure Mobility Strategy. She leads a department called the Information Assurance Directorate. For the better part of four decades, IAD has been tasked with securing secret government communications, and building specifications for the tools to do it. The NSA contracts with private suppliers to build a class of devices it calls GOTS (government off-the-shelf). The gestation cycle for each of these devices – from the conceptual stage, to development, to deployment – typically consumes years. Perhaps the best-known GOTS product is still in wide use today – 1987’s STU-III secure telephone, which looks about as home on an agent’s desk today as an IBM PC.

Still, as Salter told the RSA attendees, for the better part of half a century, the NSA explicitly defined its own market, a private universe of products made for its own exclusive consumption. “That was cool for us, for the longest time. We kinda had a monopoly on this from the very beginning,” she remarked. “We were mostly building things like radios for combat, [and] big link encryptors to hook one site up to another site.”

But their ease of use ranked right up there with a World War II cipher machine. “Once you get something in the hands of an individual user who’s not a cleared COMSEC custodian, someone who knows what they’re supposed to be doing with this stuff and understands all the details, ease of use became incredibly freakin’ important. And it turned out that, although our stuff was incredibly secure, it was not incredibly easy to use.”

Over time, it became more difficult over time for the agency to define “ease of use” on a comparative scale. In just the last five years, the consumer universe appeared to leave the NSA’s secure market behind. “The world everyone wants is, I want to get what I want, when I want it, where I want it.”

Salter’s team considered whether it was feasible for NSA to utilize a real, commercial smartphone – one like all the kids are using nowadays – but with software that made the device perhaps more secure than the Sectera Edge. “The phones are so popular and exploding all over the place, because we can play Angry Birds on them, and do whatever you want. But we needed enterprise management – some control over it, because honestly, we didn’t really want you to be able to go load Angry Birds on your TS [top secret] phone… That was not a business model that we could support, or even defend.”

They launched Project Fishbowl, a pilot to produce a smartphone made of mostly commercial parts and infrastructure (more COTS than GOTS), capable of supporting classified voice and data, while remaining as easy to use as its civilian counterpart and staying inexpensive. The historical significance of the NSA embracing commercial crypto standards cannot be stressed enough. Anyone familiar with how RSA came to be in the first place will recall the fights its engineers faced keeping the government from classifying it, taking its power out of the public’s hands. Perhaps the whole point of the RSA standard and the RSA conference is to promote the power of security for everyone through manageable encryption.

“So one of the things I harp on most is, why was that so hard?” remarked Salter.

Alphabet Soup

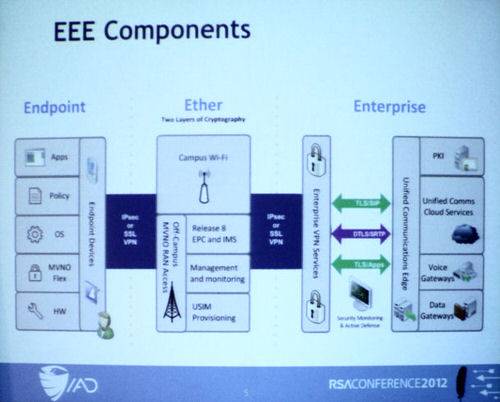

The ideal Fishbowl phone would need a securable VoIP app and a securable data transfer app. If at all possible, it should not have to be tied to any single carrier. It needed to be capable of connecting to the Wi-Fi network supplied by “the Ranch” (headquarters). It would need to be remotely manageable using policy, and all of the traffic through the phone must be routed through the enterprise manager. “Because if we allowed it to go all kinds of different places, we lost all control,” Salter said.

What appeared at first to be the protocol of choice for digital voice was SRTP. “Turns out, getting the key management scheme nailed down for that was hard,” she said. Finally, IAD was able to work out a way to do this using Transport Layer Security – which it also discovered was preferable to SSL for every other conceivable purpose as well.

NSA set out to endow Fishbowl with support for public cryptographic standards that were good enough, in combination with one another, to enable Classified-level communication. NSA calls these standards Suite B. “For encryption, it’s AES at the 128- and 256-bit strength. For key exchange, it’s Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman – and we’ve got two NIST curves, the P256 and the P384. For the signatures, it’s Elliptic Curve DSA, with those same parameters. And we add a hash function, which is the SHA-2 series. We needed those, because they’re the cryptography that’s strong enough to protect Classified.”

None of these standards are unfamiliar to the security community. Six years ago, said Salter, NSA announced Suite B as good enough for Classified level. “Then there was a big asterisk next to that,” she added, “that said, ‘By the way, your key management has to be reasonable, and NSA has to look at it to make sure it’s all good.’ We were trying to give the industry a lead time, to say eventually, if you’ve got these algorithms in your products, we’ll be able to use them in solutions… to protect classified information.”

Salter describes the “shopping” process for commercial products capable of meeting this frankly ordinary level of encryption, as “hard… We went shopping, we had our little bag and our little list, and we were wandering around looking for stuff. And one of the things we were wandering around looking for was a Suite B IKEv2 IPsec app that ran on a phone. That was a difficult shopping list to maintain.”

Voice traffic needed to be encrypted twice – once through IPsec and once again on the VoIP layer through SRTP. This was in keeping with a design principle the NSA calls “the Rule of Two:” As Margaret Salter described it, “Two independent bad things have to go wrong in order for an adversary to take advantage of your phone or data.”

But at first, NIST suggested not SRTP but DTLS. NSA had no reason to question that recommendation, so it went shopping for a phone with both DTLS and SRTP, using the “Rule of Two” as justification for both. “We couldn’t buy one. We could pay someone to make it, but that wasn’t the plan. The plan was to be able to buy commercial components, layer them together, and get a secure solution.”

The part was not to be found, for reasons Salter attributes to the industry paying attention to a feature that NIST hadn’t considered, called session descriptors – headers that describe the content of media being exchanged in a VoIP traffic session. “Unified communications is more than just making a phone call,” she explained. “There’s presence, conference calls, and all these cool things they show you they can do… and the only way to do that really is to use that session descriptors protocol rather than break up the DTLS.”

But none of the session descriptors protocols in use supported the upgraded TLS 1.2 – the substitute for the deficient SSL – and few of these protocols enabled client authentication. This was necessary in order to avoid an engineering technique called split tunneling, which Salter described as a kind of intentional leak that might be acceptable for some businesses but not for national security.

From Logjam to Android

Fishbowl phones do exist now – in fact, two of Salter’s NSA colleagues in the audience had some. But the working models made significant compromises, which Salter appeared to hold out hope could be remedied.

“We didn’t pick any of these vendors because we think they’re sensationally better than the other vendors, in any of these classes,” Salter explained to one questioner, who had asked whether Fishbowl’s choices were indicative of any degree of hardware or software superiority among smartphone standards. “We picked these vendors because we were trying to put a puzzle together. And as we picked certain puzzle pieces, other puzzle pieces fell into place… Why is the Fishbowl phone an Android phone? Because iOS is lousy? No, that is not at all the reason why. It turned out that, because of certain controls that we needed, we were actually able to do modifications to the Android OS, and we didn’t have that control over the other OSes in the space… But it is not our intention to only use Android. It is our intention to use any OS that meets our requirements.”

NSA’s vendor of choice, for now, is Motorola. But that’s because the voice app Fishbowl needed ran on that Motorola phone first. “It worked, but… Android is not Android!” Salter proclaimed. “Android is whatever the handset vendor or the OEM chooses to put on the phone! And that is another one of the rude surprises we had when we were going through all this.

“One of the things we should be demanding,” she stated at another point, “is that voice apps that do these protocols interoperate with one another. Why in heaven’s name don’t they?”

Later, a questioner from the audience offered an answer: He noted that, despite the rapidly accelerating changes in mobile technology, the customer does not appear to be in charge of what those changes are, who’s in control of them, or where they are leading. Perhaps any large group of companies, whether in private industry or the government, should be capable of laying down the law when it comes to the foundations and standards they’ll accept for phones purchased in mass quantities.

“I think for us, our mechanism is going to be to publish everything as widely as humanly possible,” replied the employee of a government secrets agency, “and hope to heck that this makes sense to people… We’ll say, ‘This is our architecture that we’re doing for mobility,’ and other corporations will say, ‘Hey, somebody did all this work for us!’ And hopefully just take it, show it to their vendor, and say, ‘I want one of these.’ That’s our hope.”