We’ve written here before in ReadWriteWeb about the bad side of Android platform diversity: multiple phone manufacturers with one or more carriers apiece, simultaneously supporting more than one active version of the operating system. One can’t help but think that Microsoft has handled Windows platform transitions better than this, but then again, Windows doesn’t have to appease the interests of carriers and manufacturers.

Now, an intensive 12-month study by mobile communications analysis firm WDS Global has come up with a quantifiable metric for the cumulative effects of platform fragmentation on carriers, and subsequently on consumers, based on estimates of 2011 Android smartphone shipments: The frustration from customers who have been unable to resolve their hardware and software issues through customer support, and end up returning their phones for replacement, ends up costing U.S. carriers a combined total of $2 billion annually.

Contrary to numerous reports, the WDS report published yesterday did not say that Android-based smartphones were more susceptible to hardware failures or problems. In fact, the report explicitly states, “Android devices are no easier, nor more difficult, to troubleshoot than a comparative product from an alternate OS vendor.” What the report states is that Android smartphones (excluding tablets), by virtue of the multiplicity of versions actively in the market, incur more carrier costs with respect to time spent conducting customer support, coupled with the wide array of brands both large and small that carriers find themselves supporting.

“At the point-of-sale many consumers (and retailers alike) are assuming a degree of consistency across Android devices that in some cases doesn’t exist,” reads the WDS report. “Even migrating from one Android device to the next can bring about problems as consumers’ expectations for performance are dismantled by a different hardware build and by potentially resource-hungry operator and manufacturer overlays.”

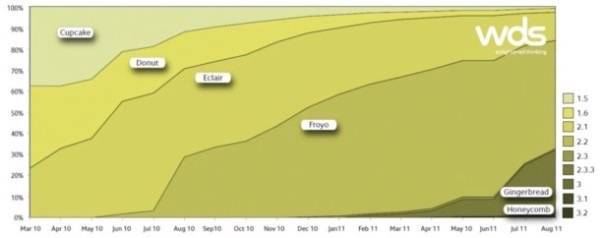

Monthly fragmentation of actively supported Android versions since March 2010. [Courtesy WDS Global]

For instance, first-time customers of the Android Market end up learning (often the hard way) that certain apps will not work with their specific build of Android. In some cases, modifications and permissions made by carriers themselves end up conflicting with installed apps. And when carriers’ support representatives help their customers upgrade to newly supported Android versions once it does become time, customers discover a few extra, unanticipated surprises.

“In one example from 2010, a UK operator was forced to apologize to its customers after fielding a storm of complaints from users unhappy with the addition of ‘bloatware’ – unnecessary software added by the operator that couldn’t easily be removed, in an Android 2.1 update,” the report preaches to the choir. “Customers complained that the additions slowed their devices and inhibited some functionality (including SMS notifications).”

Do we know the additional costs carriers may be incurring during the customer support phase itself, before customers turn in their phones for replacements? RWW asked Tim Deluca-Smith, WDS’ Vice President for Marketing: “As for additional support center costs, the actual cost of supporting Android in the ‘traditional’ sense is no different to other platforms – i.e., the duration of a tech support call, and the propensity for a customer to call with a problem is consistent with other platforms,” Deluca-Smith.

“The real cost comes in the fact that hardware faults add logistics costs,” he tells us. As the firm tries to make clear (but may be having a hard time accomplishing), it so happens that smartphones that happen to run Android are the ones with the hardware troubles. Android itself, WDS believes, is not the reason.

“While Android deployments may show a higher propensity to hardware failures than rival OS platforms, analysis of these hardware faults shows no principle defects on the platform; i. e., the platform is not predisposed to one particular hardware defect,” the report reads. “Instead, the distribution of hardware faults against weighted averages deviates by less than 1% in all categories. In this instance, Android actually benefits from deployment across multiple reference designs and component variants. This means that the brand is unlikely to be associated with a specific hardware shortcoming.”

Two of the metrics the WDS team examined were average handle time, which refers to how long it takes customer support at any level to devote to a customer issue; and propensity to call (PTC), which refers to the likelihood that a shipment batch of 10,000 or so devices will generate support instances at a high, “tier-3” level. While AHT is typically a function of the quality of customer support, PTC is a function of the complexity of the hardware and its supporting firmware, and is tallied as the ratio of phones returned to phones shipped. If PTC eclipsed the 15% mark, carriers would attribute that figure to defective phones. As it stands for 2011, WDS estimates PTC for Android phones at 14%, and the ratio of incidents actually attributable to hardware failure in the end at 12.6%.

By contrast, Windows Phone 7 PTC rates for the year are about 11%, with hardware failure at 9.3%. Apple iPhone failure rates for the year are likely to top out at 8%, and for RIM BlackBerry, 5.5%.

“You could make the assumption that, while traditional support costs are consistent,” says Deluca-Smith, “the average profitability of a batch [shipment] of devices is reduced because of the reverse logistics / repair costs.”

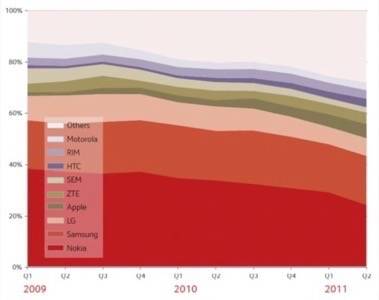

Quarterly breakdown of carriers supporting Android since Q1 2009. [Courtesy WDS Global]

Android has helped smaller manufacturers enter the industry sooner, and make a dent in the market. The result is what the industry calls the “long-tail effect,” using a term that may have spread with the help of a July 2009 WDS report (PDF available here). That report suggested carriers could create competitive mobile e-mail service alternatives to then-leader BlackBerry, and go with less expensive, but still compelling, competitive models. Android wasn’t a factor at that time.

WDS’ Deluca-Smith tells RWW he believes carriers must adapt now to the new reality of the long tail, suggesting that at this point, the only ones who can resolve the rising costs of supporting Android are the ones doing the supporting.

“Android has done great things for the industry, even low-cost product,” he says. “However, carriers must be better at bringing the variety of Android builds onto their networks. Low cost has its place. It shouldn’t be used across all customer segments as a means to reducing subsidy costs.”