At the end of 2011, the mobile industry believed that HTML5 was on the cusp of ubiquity. Everybody would be using it to build apps and mobile websites and we would finally see real operating systems based on HTML5 start creeping towards acceptance. HTML5 was to become the dominant development stack, taking the mantle from all those native apps that had come to dominate the iOS App Store and Android’s Google Play.

What actually happened is that HTML5 more likely took a step back in developer acceptance in 2012.

Facebook Goes Native, Apple Cripples Webview

Facebook has long been a proponent of HTML5. The social network’s “native” apps on iOS and Android were actually mobile websites “wrapped” to give native fixtures to the apps for Android and iOS (among other platforms). Yet, Facebook eventually came to find that this system was not optimal for the performance of the apps. Yes, using the m.facebook.com mobile website as a base that could be updated multiple times a day made for efficient development cycles, but in reality the apps were slow and buggy and users often complained that Facebook’s native apps were simply not very good.

Facebook decided to change that in 2012. In August the social network relaunched its iOS app to straight native code, improving its performance. More recently, Facebook redid its Android app as native code in December.

Facebook and its “hacker culture” is, like it or not, a beacon for mobile developers. If Facebook is going native for performance reasons, then others will follow in the footsteps of a company that serves nearly a billion users, over half of them on mobile.

Apple has some blame in the blowback against HTML5 in 2012, too. The iPhone maker has limited UIWebView in iOS Safari, causing hybrid and Web apps to perform slowly in comparison with native apps. It behooves Apple to limit the functionality of HTML5 and Web-based apps, as its App Store is one of the primary reasons that people buy iPhones and iPads. Mobile Web apps that circumvent the App Store are, in several ways, dangerous to Apple’s bottom line.

Hybrid The Name Of The Game

Despite Facebook’s move to native apps, more and more developers are incorporating at least a little bit of HTML5 into their apps. For instance, the new LinkedIn app released in 2012 was almost entirely HTML5 and Node.js with only a thin native wrapper that made up about 5% of the code.

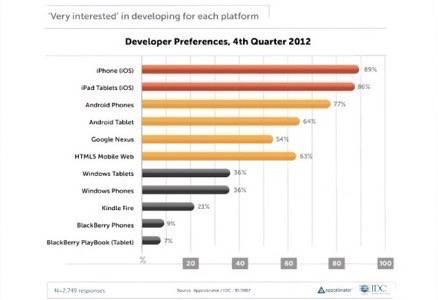

According to the fourth quarter survey of mobile developers by Appcelerator and IDC, about 63% of mobile developers are “very interested” in using HTML5 to build their apps. Many developers are building 50% or more of their apps with HTML5 code. Many apps are including some type of Webview into their apps (for instance, see how social news reader Zite lets you read an article on through the browser or in the app). With the app economy exploding, we now see thousands of apps use the hybrid wrapper model to increase the efficiency of building an app and lower the overall development costs.

One reason for hybrid development is that it is easier for many companies to find developers who are versed in HTML/CSS than it is to find coders who have the specific knowledge on how to create comprehensive native apps in C, Objective-C etc. By working with HTML5 and wrapping apps, companies (that may not necessarily be tech companies per se) can get more length from their developers and hit more devices in one shot.

Dealing With The Problem Of Hardware

The biggest difference between HTML5 mobile Web apps and native apps are that the native variety have quick an easy access to a smartphone’s hardware features. That means functions as simple as the clock, vibrator, gyroscope, storage, camera and power management are much more difficult to implement in pure HTML5 apps. Developers have dealt with this problem in the past through services like PhoneGap or Brightcove’s App Cloud and wrapping Web apps for native purposes (like Facebook used to do).

Companies are beginning to crack the hardware puzzle for HTML5 apps. Mozilla is on the forefront with its Firefox OS, expected to be shipped on smartphones sometime in 2013. Mozilla has created what it calls Web APIs that will tie its browser-based HTML5 mobile operating system to hardware components like power management and the camera. Sencha and appMobi are also working on ways to bridge the device APIs. As of yet though, progress in this realm was not as robust in 2012 as many expected.

The Responsive Design Revolution

Responsive design saw a boom in 2012. Responsive design is built from a Web technology stack that includes HTML5 and CSS to create websites that respond to a variety of screen sizes by automatically resizing windows to fit a particular screen. The purpose is to build one set of code for a website that allows it to work on multiple devices without having to build separate sites for individual devices or mobile operating systems.

For instance, take ReadWrite. This year we launched a new website in October that is fully responsive. Check it out. In this story, make the browser window bigger or smaller and you will see the content respond accordingly. Or try zooming the browser view in or out and note the same thing. The same goes for mobile. Read this article in smartphone and note how it perfectly fits your screen. On a tablet, look at it in both landscape and portrait modes and see how it adapts to each set.

In conjunction with our responsive design relaunch (and subsequent rebranding from ReadWriteWeb to ReadWrite), we ditched out native apps on iOS and Android apps in favor of the simpler, easier to update mobile Web presence.

We are not alone. BostonGlobe.com rolled out its responsive design site in 2011 and About.com is now fully responsive. The New York Times has built a responsive site and large companies like Microsoft and Apple use responsive design on aspects of their websites.

The Leaders Are Changing

In 2011, we said that the game developers of the mobile world were taking the lead in HTML5 development. At the time, that seemed true. Yet, the game makers lost interest in HTML5 as a default platform in 2012. True, companies like appMobi are pushing game makers toward HTML5, but most of the best games of 2012 were built with native code.

To a certain extent, the leaders in HTML5 adoption are now media companies and news organizations. Those in the business of content are more apt to take a Web-centric view of the world. By doing so, they can avoid the 30% tariff from Apple’s App Store, while still optimizing content towards mobile devices. This trend is not precisely tied to HTML5, but the current evolution of the technology stack makes it much easier for media companies to achieve this objective.

Facebook was seen as the quintessential leader in HTML5 development in 2012. Yet, with its move to native for iOS and Android, it has ceded that role to the community. As such, open source developers spearheaded by the likes of Mozilla are now the leaders that will drive HTML5 for the foreseeable future.

Lead image courtesy of Shutterstock.