When Google and others ganged up on Facebook a few weeks ago,

to many of us, Open Social looked like a marketing move. The news came

suspiciously close to Facebook’s ad platform announcement and after a close look, the API looked very raw. Most participants just announced their

support without having any concrete implementation.

Yet, Open Social is not a

fluke and neither it is an accident. It is an important step in the evolution

of social and open web, a step that we have seen taken before in other circumstances.

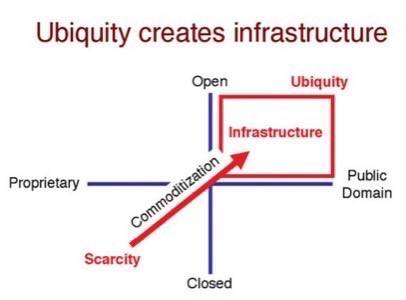

It is called commoditization. By creating an exchange of gadgets and social information

Google and Co. declared that the era of social silos is over.

In this post we look at the details of the open social API, discuss its adoption

and look into the future of the social web.

What is Commoditization?

Commoditization is a standard point in any technology cycle. First, when we invent something new

it is scarce. Think back to the first cell phones. The prices were high and people were standing in line just to get one.

As the technology gets refined and phones become cheaper to make, more of them are thrown into the

marketplace. More companies get into the act and prices drop. The end result? Seven year olds are running around with

cell phones today because they are free.

The diagram above is from Doc Searls.

Cell phones became a commodity just like TV and transistors and DVD players and even computers.

Once something becomes a commodity it turns into a platform on top of which new stuff can be built.

Because the majority of the US population has a cell phone, there is a big opportunity for

the wireless platform – calling, accessing the web, playing games, and so on. Commodities also

drive standards because there is no competitive know-how left. If everyone knows how to make cheap phones

there is no reason to tie the phone to a particular service. Granted, in our telecom industry things are much more complicated, but you get the point.

Historical Look at Java-based Application Servers

One of the most recent examples of commoditization in the software industry is the rise of Java-based application servers.

An application server is a container for running enterprise applications. It is, in essence, a sandbox that abstracts away

enterprise services – application deployment and monitoring, database access, web access, queuing, security, etc. Initially several incompatible products were

on the market, most notably from BEA and IBM. The incongruence between vendors meant that companies could not develop

portable applications – each application had to run on the software from a specific vendor. This created a lock-in and reluctance in

the marketplace.

Things changed when, under the leadership of Sun Microsystems, the Java community authored a single standard specification for an application server.

Sun, Oracle, BEA, IBM and many others implemented the specification in their product. This meant that each application server now had a standard

application packaging, deployment and execution. Because everyone complied, the applications became portable. Well, almost – the truth

is that vendors still have proprietary things in their systems, but it is much easier to move applications around.

What is Open Social?

Simply speaking, Open Social is like a specification for Java Application Servers except that it is a spec for hosting

applications and widgets inside social networks. Specifically, Open Social defines the following three broad areas:

- Widget/Application API

- Friends API

- Activity API

The Widget/Application API is similar to the Facebook Application API. It defines a protocol between widgets/applications and the social network (the container).

A widget written according to the protocol is guaranteed to work in any social network that supports it. As an example, if you write a widget for iGoogle it will also work

on Ning. This is because both of these environments have implemented support for a common widget format. This format itself is very straightforward and is based on the

existing Google modules. Each module is an XML file which describes the properties of the widget and contains JavaScript code for it. The deployment process

typically consists of putting this file on a network and then specifying a URL on the social network’s configuration screen.

The Friends API allows external applications to query a piece of the social graph inside the social network.

Based on explicit permission from the user, applications may get a list of his or her friends. This is important, because it unlocks the social graph.

For example, Flixster holds a piece of your social graph that defines people who like similar movies, basically your movie friends.

If Flixster implements Open Social then you could send this information over to Netflix. This is powerful and important, because it empowers

consumers to control their data and saves people time by helping information from one service bootstrap another.

The Activity API is designed to both import and export the user activity from the social network. It is similar to Facebook’s news feed and Beacon ads,

except that those are not exportable. Examples of this include things like: Alex posted a photo to Flickr or Alex twittered that

he is on a plane. And also for the activities inside the network: Alex and Richard just became friends or Alex is attending the NYC Tech Meetup.

The first API is really about portability of widgets and applications, while the second and third are about portability of the social graph

and attention information. All of these still have a long way to evolve but they bring powerful concepts of openness and interoperability

into the social network marketplace.

What is the Impact on Developers?

The slogan: write once, run anywhere, is music to the ears of any developer. Having to support a piece of code

that is targeted towards many incompatible platforms is a nightmare. With Open Social, widget and application developers will

be able to have a single, hopefully simple, code base. The direct benefit is that developers can focus on the essence of their offering

instead of having to deal with infrastructure and portability issues.

The fact that the same piece of code can run on many social networks is also likely to encourage more companies to

enter the widget marketplace. Prior to their announcement of Open Social some companies may have been reluctant because

the cost of creating specific widgets for each network might have been prohibitive. With Open Social, there are no longer any excuses.

Investing in a widget or a widget set that can be deployed across a wide range of social networks is a no-brainer.

So What About Facebook?

Commoditization of social networks is not good for Facebook. It has been positioning itself as a leader, a unique place

that connects people in the just the right way. The Facebook platform is what made Facebook into “the company” of 2007. If everyone has

the platform and not a proprietary, but standard platform, then Facebook’s value shrinks back to the size of its current audience.

Despite the fact that Open Social is a big stone thrown at Facebook, it is still doing fine. With close to 60 Million users and the deal

with Microsoft under its belt Facebook is likely to continue its march forward. It is also likely to join Open Social. Being an odd duck in this

situation is not going to fly well with customers. There is a chance that it is going to play the Apple “we are the best and closed” card, but

it is a rather small one. Facebook is not going to loose much from joining Open Social. In fact, like IBM some years ago embraced the open source,

Facebook can do the same with Open Social. If it does, it might actually own it and cancel out the impact that Google and Co. is trying to make.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Open Social is a major step towards opening up web silos. As we have previously discussed here, most companies on the web have been silos.

From Amazon to Netflix the companies have held on to the user information that they gathered, turning it into a business advantage.

Open Social paves a way to a potentially new kind of web culture. In that culture, companies would recognize that users are entitled to

their information. It should be importable and exportable. It should not be locked in.

If Open Social is implemented on the broader scale, there is likely to be a cultural shift. Consumers are going to recognize that

if their social graph is portable and if their attention information is portable in social networks, then it should be portable at large.

People are going to demand that their Amazon purchasing history and Netflix rental history is accessible via open API.

If that happens, we will effectively enter the age of the attention economy.

Now tell us what you think of Open Social and its implications. What companies would you like to see join this initiative?

What do you think about Facebook’s play, will it join the initiative or remain closed?