OpenStack rules the open-source cloud. Which may simply mean it’s the tallest person in Lilliput.

With Amazon Web Services (AWS) paving the way for enterprises to move their workloads to the public cloud, including in-house apps, OpenStack’s reign as open cloud sovereign may be short (if not nasty and brutish). The open question is whether OpenStack is a “poor man’s vCloud” or whether it actually fills a long-term and growing need for big organizations.

OpenStack’s Billion-Dollar Promise

No one questions OpenStack’s community bona fides. For years it has attracted thousands of developers to the semi-annual OpenStack summits.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that OpenStack would poll really well in popularity contests. According to a new Zenoss survey, 69% of the roughly 400 respondents are using a cloud, and 43% of these respondents are using an open source cloud (e.g., OpenStack, CloudStack, Eucalyptus, etc.).

Among these open-source competitors, OpenStack stands out, with 69% choosing the community leader.

This, in turn, seems to be translating into real revenue.

For example, 451 Research predicts that the OpenStack technology market, which produced revenue of $883 million in 2014, could top $3.3 billion by 2018.

Most of this OpenStack revenue derives from service providers like Rackspace, which means that much of this revenue comes from Rackspace itself. Rackspace projects its OpenStack-based public cloud business will hit a $1 billion run rate by early 2016, though based on current growth it’s unclear how it gets to that number.

For its part, Red Hat got into the OpenStack game in earnest in 2013, but has publicly said it wouldn’t make much OpenStack revenue in 2014. And it hasn’t. But that may change, as I argue below.

Regardless, even $3.3 billion in OpenStack revenue by 2018 simply means that OpenStack will remain a distant third place to AWS (and Microsoft Azure, not to mention Google) forever.

There are good reasons for this.

Clouding The Cloud

After all, according to the Zenoss survey, the top three benefits expected from open source cloud deployments included lower cost of ownership (71.1%), agility (55.6%) and better uptime (46.7%). At least two of those (agility and uptime) are almost certainly more consistently delivered by AWS rather than some in-house team fiddling OpenStack nobs and gears.

One primary reason for shifting to public cloud services is to get away from a cumbersome, IT-driven service provisioning. It’s not clear how OpenStack changes this much. As one person told me, OpenStack is “for IT folks that want to stay on-prem, but fool their execs that they are doing ‘Cloud’.”

Or as Andy Jassy, Amazon’s cloud chief, puts it:

If you look deep into what [private cloud vendors] are offering, you will see that it’s basically an internal data center that is virtualized and has some management tools. Organizations that have private cloud systems will have missed out on all the advantages and benefits of going into the cloud.

That’s hardly a recipe for long-term success, even if Dell’s Joseph Jacks correctly surmises that OpenStack “will be the defacto [infrastructure-as-a-service] fabric for self-service cloud consumers in enterprise IT for some time to come.”

Red Hat To The Rescue?

As such, it’s highly likely that many workloads will stay behind the corporate firewall for the foreseeable future. In such a world, OpenStack’s big proponents can expect to make a lot of money. Foremost among these will be Red Hat.

Red Hat, more than any of the other OpenStack vendors, has a long history of hardening open-source code and selling it to the enterprise.

This, perhaps more than anything else, is what OpenStack needs today. As Gartner analyst Lydia Leong has suggested, OpenStack desperately needs a “core” that is “small, rock-solid stable, and readily extensible.”

She goes on:

There’s much work to be done still, but things are grinding onwards in an encouraging fashion. The will to solve the common problems of installs, upgrades, and networking seems to have permeated the community sufficiently that these basic elements of usability and stability are getting into the core. The involvement of larger vendors has created a collective determination to do what it takes to make enterprise adoption of OpenStack possible, in due time.

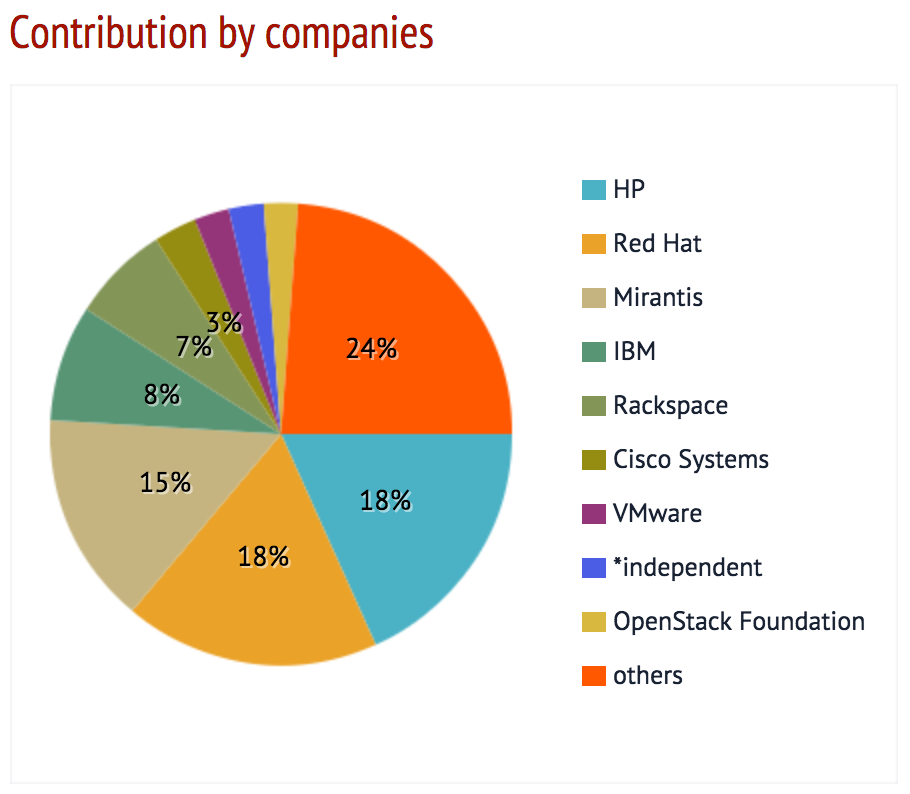

In just a few years, Red Hat has gone from zero involvement to top contributor to OpenStack, putting it in a great position to ensure OpenStack gets the “rock-solid core” it requires.

Meanwhile, whether you think private clouds are fake or real, enterprises have been turning to OpenStack to build private clouds, as OpenStack survey data shows. Between November 2013 and November 2014, OpenStack saw production deployments jump considerably, moving from 32% to 46% of survey respondents.

Open source being open source, “production” doesn’t necessarily translate into “revenue” for OpenStack vendors. Even if it did, this increased adoption almost certainly won’t add up to the $5 billion in annual revenue that AWS reportedly already generates.

Still, “eking out” a few billion of revenue from companies too skittish to leave their data centers behind? That’s revenue that Red Hat will gladly take.

Lead photo by George Thomas