If I were truly mischief and wanted to game the system, I would have named this article, “Facebook Wants to Be Your One True Login, Part 2.” If you’re not familiar with the incident to which I’m referring: One of the most illustrative cases of the incomplete state of the Internet as an information system was in February 2010, when ReadWriteWeb itself happened to publish an article with “Facebook” and “login” in its headline. It soon found itself at or near the top of Google search results for the phrase “facebook login,” with the result being that hundreds of Web users to this day happen upon this page when they’re trying to reach Facebook itself.

The Web was not designed to require identity or authentication for data to be accessed. Up to now, most consumers have not considered this a problem – at least, not the ones who found themselves staring at ReadWriteWeb when they were expecting Farmville. This will change.

Too many protocols, too few sources

The one emerging fundamental truth from the Web as a technology is a strange, sideways corollary to Murphy’s Law: If a system can be gamed, it will. As the Web evolves, and as HTML5 is implemented by more organizations for delivering applications, the Web will come to rely more and more upon the very component it was designed from the beginning to intentionally dis-include: identity, the need for which is said by its earliest engineers to be contrary to the notion of openness.

The way the first Web services distinguished between individual users was by storing session data on client systems in the form of cookies. This system was largely distrusted and, like all such systems online, became the subject of considerable gaming and malicious abuse. Its eventual unreliability, coupled with the fact that a cookie was only meaningful to the service that created it, led to the need for a new standard for establishing trust between server and client – one that would be less ridiculous than SSL.

The rush to fulfill this need led to an over-abundance of competing protocols, and an even greater number of so-called federation mechanisms for enabling these protocols to cooperate with one another. Amid all the confusion, developers of the first wave of genuine cloud-based SaaS applications find themselves relying on the most abundant, readily available solution at the present time: a combination of OAuth 2.0 for enabling a channel for one authority to grant permissions to another, and an identity protocol such as OpenID for exchanging identity tokens over that authorized channel.

Taking advantage of this new reliance are the networks which have the most to gain from absorbing as much data as possible on users’ activities: Facebook, Google, and Yahoo. And in its forthcoming Windows 8, Microsoft will place its Windows Live ID front-and-center, making it the preferred password-based logon system for Windows-based PCs and tablets. This leads to a kind of tangled conundrum that only our modern society could have bumbled into: The problem of safeguarding access is effectively being outsourced to the very centralized sources that are the crux of the existing problems with privacy and user security.

Pairing identities with profiles

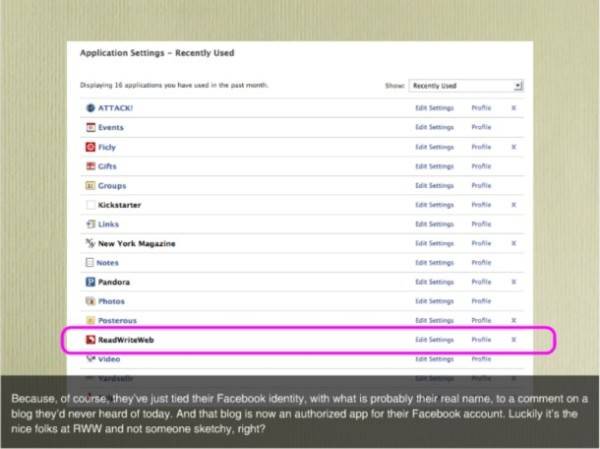

In a March 2011 session for the SXSW conference, Webroot security engineer James Reffell borrowed ReadWriteWeb’s own “facebook login” incident to illustrate the effects of identity centralization. When unknowing users stumbled onto RWW, many of them actually ended up logging onto the Facebook Connect service anyway, since FC is one of RWW’s identity providers. As a result, folks ended up associating themselves with Facebook as comment contributors to RWW, even though the comments they were contributing consisted mainly of cries for help.

What makes this data valuable for centralized ID providers is its ability to be aggregated and analyzed. This is why Facebook and other services are calling for a one-to-one relationship between users and activities, and for users’ online identities to be unique and, shall we say, unvarnished. Last November, the extent of Facebook’s efforts was revealed when Facebook changed novelist Salman Rushdie’s profile to use a different first name – the one that appears before “Salman” on his passport. Rushdie objected because folks wouldn’t recognize “Ahmed Rushdie” as the famous novelist – and accessibility by his readers was one of the whole points of adopting a Facebook identity in the first place.

What wasn’t determined was whether Facebook chose to look into Rushdie’s passport profile simply because he was Rushdie, or whether there’s a larger, ongoing process of checking everyone’s online handles against their passport names.

Whether he intended to game the system or not, TechCrunch contributor M.G. Siegler discovered yesterday that his Google + profile picture had been removed for having displayed the middle finger in a solo setting. The original, unaltered arrangement may be found on Siegler’s Twitter feed, which incidentally uses a nom de plume. Although the Google + terms of service do explicitly forbid the use of potentially offensive material, Siegler found it odd that Google would be actively policing the relative stances of its users’ hands. “In certain cultures, various hand gestures mean different things,” he wrote. “Is Google also going to delete my profile picture if I have my fingers up to my chin, for example?”

The odd coupling

The problem at hand is that Web apps developers are now entrusting the job of validating identities to services that have an interest in cleansing them. There are perfectly valid reasons why a social network provider would want to maintain both order and equanimity in its users’ profiles. There are equally valid reasons why whatever information is conveyed to a service trusted with validating individual accounts, should only include data that is directly accessible to the parties in the transactions to which those accounts pertain. These two sets of reasons are incompatible with one another at multiple points.

Yet de-coupling transaction accounting from identity provision disables the entire value proposition for social networks. In other words, if Facebook and others could not potentially monetize the data they were collecting from folks logging onto apps and blogs and stumbling onto strangely fortunate headline choices, they would have to find revenue elsewhere – perhaps from subscription fees, which at this point users are unwilling to consider.

In the meantime, there may be no immediate incentive for developers to build a more viable solution: a kind of personal portfolio service where Salman Rushdie’s name and M.G. Siegler’s middle finger remain untouched, but whose personal data is only used by them and the services and retailers of their choice for their own purposes. Need alone does not generate solutions, otherwise Web users (which include online bankers) would not have had to suffer with the dangers of SSL encryption for well over a decade now.

However, the longer we wait for a solution to materialize, the more opportunity we give for someone – intentionally or not – to exploit the problem.