If you’ve ever dreamed of sending a satellite up into space to measure the Earth, an education-technology company is making it possible.

On Wednesday, Ardusat is publicly launching a program to offer “space kits” with programmable sensors that it will place in small satellites in partnership with commercial satellite company Spire.

The space kits cost $2,500, but the company has made the curriculum and online resources available for free. And through a partnership with the Association of Space Explorers, a global professional organization of cosmonauts and astronauts, along with a grant provided by Northrop Grumman, Ardusat is running a science competition beginning Sept. 2 to provide 15 high schools with a free space kit and the opportunity to work directly with an astronaut.

Already, more than two dozen schools are currently using Ardusat, and with its public launch, the kits are available to everyone.

Space Dreams

Ardusat’s program struck a chord with me: When I was in second grade, I wanted to be an astronaut.

We’d just memorized the names of the nine planets—this was before Pluto had been struck from the list—and used glue and papier-mâché to build our own solar systems. That was about as hands-on as our learning ever got.

The next month, we learned about the ocean, and I wanted to be a marine biologist.

If I’d had the opportunity to send something up into space, perhaps my passion for discovering faraway stars and galaxies might have stuck around a little bit longer.

A Payload With An Educational Payoff

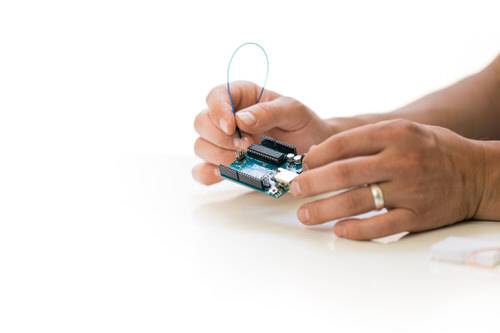

Ardusat’s “space kits” contain an Arduino board—a cheap, widely available circuit board for DIY electronics projects—and multiple sensors that can be programmed to capture data on temperature, luminosity, and magnetic fields.

The students can program the sensors using Arduino to test scientific hypotheses based on data that can be measured from satellite orbit—for example, finding the relationship between El Niño weather conditions and the ocean temperature near their schools. (Ardusat is a portmanteau of the words “Arduino” and “satellite.”)

Once students are finished, Ardusat tests their code for bugs and sends the project to a Spire satellite. Each of Spire’s satellites have something called an “education payload,” or a set of sensors used for educational purposes, where students’ projects will reside. Students can configure the projects in real time to collect different data.

The satellites, called “cubesats,” are about the size of a softball. They are designed to orbit the Earth at 2,000 kilometers above the surface for nine months to two years, before reentering the atmosphere.

“There aren’t a lot of great STEM programs in education today, and it’s not because there’s a lack of materials—it’s just that it’s not engaging for students,” Sunny Washington, president of Ardusat, told me in an interview. “We’ll want to capture the interest of these students early on, and make space accessible to them, so hopefully they’ll be encouraged to pursue a STEM career.”

Satellite sensors will capture data and send it back to students in real-time, so classrooms can monitor how the experiment is performing each day. Ardusat offers pre-programmed sensors, so if students are unable to program Arduino, they still have the opportunity to send sensors up into space.

“We’re trying to encourage high school level people to take a look at science, technology, engineering and math, and see whether or not that’s something that excites them for their future,” John-David Bartoe, a retired NASA astrophysicist and treasurer of the Association of Space Explorers, said in an interview. “It gives them the opportunity to get a taste of a very interesting field, and a very cool opportunity to operate a real satellite.”

The group hopes to continue this competition annually, to provide low-income schools an opportunity to operate a satellite at no cost to them.

Ardusat In The Classroom

Rachelle Romanoff is a physics and chemistry teacher at Bakersfield Christian, a college preparatory school in the central Californian city. She was one of four contributors who helped create the Ardusat curriculum.

This year, Romanoff is bringing Ardusat to her 10th and 12th grade classrooms. Her AP Physics students are so excited to program sensors in space, some students enrolled in the class just for this particular project—she now has 23 students in the class, up from just 6 last year.

“I don’t know of any other way that they can get such a hands-on experience where they can be involved in all of STEM,” Romanoff said in an interview. “The computer programming, the science—not only with physics, but with earth science too. And math. It’s all wrapped into one.”

Because students can configure the sensors in real time, Romanoff says she’ll be using Ardusat throughout the school year. Students will write code to then send to the satellites housing their particular project. It will be crucial in helping students understand concepts like electricity and magnetic fields.

The satellites will send the data back down to Earth, and students can collect and view the data on their iPads, and make graphs out of the information received from space to observe patterns or work out hypotheses.

Want A Job? Learn About Space

The future looks dark—that is, our perception of it is expanding into what seems like an abyss. As funding for NASA gets cut, other companies like SpaceX and Virgin Galactic are dedicated to pursuing the far-corners of our galaxy, unencumbered by funding, or lack there of, from the government.

Science and technology jobs will balloon in the future, as other corporations including Google and Facebook are investing in satellites, and private companies are promising commercial space flight. But due to lack of education and interest from students, those jobs might be hard to fill.

“The space industry—I’ve never seen anything like it,” Washington said. “When you talk to the people at NASA, when you talk to other commercial companies, they are so concerned that there aren’t enough scientists, and not enough students that are interested in space to replace these jobs.”

By providing students with the ability to travel to space, or at least program the sensors to, Ardusat makes the idea of space science a promising career field for students. Not just in the U.S., but around the world.

According to Washington, the company has talked with the Mexican Space Agency, and schools in Brazil, China, Guatemala, India, Indonesia and Israel.

As the Ardusat programming gets more advanced, and more satellites become available for students, Ardusat envisions more technical experiments like thunderstorm tracking. With the control of satellites at their fingertips, more students may find the endless possibilities of a job in space appealing.

“There is no question, we will be exploring space continuously in the future, and going farther and farther away from Earth.” Bartoe said. “For us, it’s critical that the United States be a leader…. We don’t want to be left behind here on Earth.”

Images courtesy of Ardusat