John, the computer store manager, handed me a pair of five-and-a-quarter-inch floppy disks, and with his characteristic abandonment of everything resembling candor, told me in a voice loud enough for customers in the burger joint across the street to hear: “I’m not really supposed to have these. And I’m not supposed to be giving them to you. But I guess it’s too late, because I just did. So you didn’t see me.” A self-adhesive label on the top left corner of the first disk was marked in ball-point pen, “MS-DOS Executive.” That wasn’t its correct name.

He had just returned from the National Computer Conference in Chicago, which in July 1985 was the largest convention of its kind. I wished I had gone that year, but as is often still the case, publishers couldn’t afford to send me. Like many more computer store managers than he preferred to admit, he’d been given an “advance copy” of the next version of Microsoft’s task switching program, for the express purpose of spreading the word. Task switchers were very hot sellers; stores like his couldn’t keep Norton Commander or DESQview on the shelves. Earlier, Microsoft had added an “MS-DOS Executive” to a special release of its operating system for what the world called “IBM-compatible PCs,” or just “clones.”

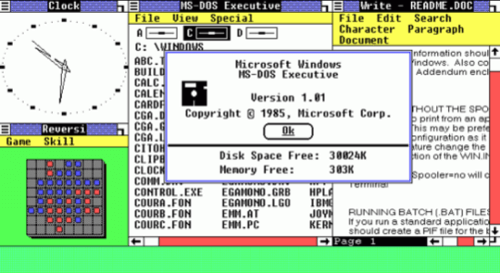

Version 0.x, 1985

Microsoft would rarely afford me the opportunity to use the phrase, “It’s like nothing you’ve ever seen before.” In the software market, there had already been a few decent efforts at graphical task switchers with “high-resolution” VGA graphics (the highest mode supported by IBM PC ATs and 80386-based machines at the time). By far the best of these had been Digital Research’s (DRI) GEM, the graphical environment Gary Kildall had originally intended to accompany CP/M (the OS that IBM passed up for MS-DOS). But DRI had been tied up in court with Apple, and thus we expected Microsoft’s next-generation “Executive” to look substantially non-Macintosh-ish. So we were not surprised.

A crowd gathered as John fired up the Columbia 386 PC, one of the first clones of the post-AT era (Compaq had already beaten IBM to market with a 386). The blue title screen came up, with an interesting special effect where blocky, white characters converged in the middle to form the “O” in the Microsoft logo. We saw the name “Microsoft Windows” for the first time. In my fake-poetic voice, I improvised Rod McKuen-like verse around the word “Windows,” before declaring it “a really stupid name.”

The problem with task switchers was that they had to remain in memory while the task was launched, so that they could resume when the task was suspended. Since most systems only had 640K of total memory, the best task switchers left only 512K free. Windows zero-point-something left about 400, which meant you couldn’t use it in an average PC AT to launch Lotus 1-2-3.

But this Columbia 386 had an expansion memory board that kicked its capacity up to a full, screaming megabyte, which was more memory, my first colleagues claimed, that should rightly ever be used in one machine. The problem with this early release of Windows was that it did not recognize every one-meg memory board available. So when we first put inserted the labeled disk in the A: drive and typed WIN at the DOS prompt, after the little “O” animation, the system froze.

It was after replacing the memory board twice, I think, and commenting out the third-party memory managers from the CONFIG.SYS file, that the graphical screen finally came up. We had a Microsoft mouse attached to this PC, which looked like a Lifebuoy soap bar with two strips of green pepper glued to it. Inside it was a steel ball like a shot put, so if you rolled the mouse and let go, it would travel on its own until falling off the desk and onto your toe.

I would write up a brief, 2,000-word Windows preview for a company that syndicated my articles in the little handout flyers that computer stores all over the country gave away. It would be reprinted in PC users’ group newsletters, and on a few hundred BBSes all over North America, by virtue of a network called FidoNet (it still exists today) where host computers literally called one another up by telephone. Despite being distributed by what today looks like the Pony Express, the article would be published prior to the product’s official release later that year, which meant I had a scoop. In it, I declared “Windows” (hopefully they’d decide upon a better name) pointless. If you had the memory expansion card you needed, then you already had the right driver; and if you had the right driver, chances are that it already shipped with a graphical executive. It was a cheap task switcher, I said, which only served to emphasize how far behind the technology curve Intel-based PCs were compared to Motorola-based devices from real companies like Atari.

While other companies were smart enough to quit after the first try, I said, Microsoft will probably keep plugging away at this for years to come.

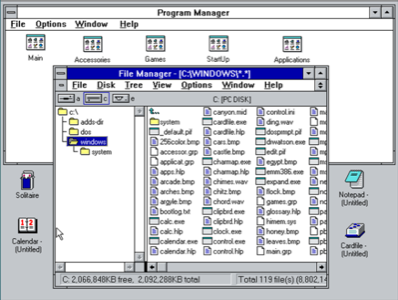

Version 3.0, 1990

In the spring of 1990, many of the original editorial crew from Computer Shopper magazine found themselves suspended by the magazine’s new owner, Ziff-Davis. As with all of Shopper’s contributing editors, I worked under contract; but nearly all of us, myself included, refused to sign an agreement with Ziff-Davis that would have severely restricted the integrity and independence of what we said in print, as well as limited us to writing exclusively for Ziff-Davis.

So a Montgomery, Alabama, entrepreneur named Doug Moore, who imagined himself the next Ted Turner, bankrolled a publication where all of us could continue to publish the same magazine as before, funded in large part by all of Shopper’s former advertisers who failed to “make the cut.” We were Computer Monthly, but Microsoft, Lotus, Ashton-Tate, Borland, and all the serious software publishers who knew us all by our first names (and me by my pseudonym) thought of us as the Shopper in exile.

Computer Shopper hired us originally because we had a knack for filling space, and it had more space to fill than any periodical ever printed: as many as 500 pages per month. My main Windows 3.0 preview story for Computer Monthly was 7,500 words, plus I added two 2,000-word sidebars. In this series, I interviewed every major executive with a major Windows 3 product to be released in tandem with the new environment. (It was not yet an operating system.) My editor, also a Shopper veteran, told me, “Mr. Scott, you’re a whole goddamn magazine!”

Microsoft had given me pre-release samples of Windows 3.0, and interviews with its key engineers. So I knew some things about where Windows was going that I couldn’t say even then. Instead, I could allude to them in the intro of my main article:

The weeklies and fortnightlies have already extolled the merits of Win3’s “three-dimensional” buttons, proportional text, and now-boundlessly managed memory. Their gold-star awards have no doubt been bestowed upon the product for being the best in its class, albeit the only product in its class. The “pundits” have already laid blame upon someone for Win3’s alleged tardiness to market. The entire story is so well-patterned that it may be read without ever having laid eyes to the printed page.

Yet if we follow the pattern, we miss the real story. There is a real development taking place between the authors of and for Windows 3, which concerns the remodeling of the computer application. We are familiar with the application as a program and its associated data, which is entered and exited like a jewelry store or a bank. We sometimes see ourselves “in” an application, just as we often see ourselves “in” the subdirectory pointed to by the DOS prompt. The data we need while we’re “in” the program is much like the diamond necklace behind the display case; we’re allowed to look at it and touch it, but unless we’re very crafty, we’re not allowed to take it outside. It doesn’t belong to us — even if the data’s very existence is due to our having typed it in.

The entire contraption of the DOS environment — along with the guilt feelings it so subtly leaves us with — are being shattered by Windows 3. There is a movement under way by Microsoft and its supportive independent software vendors (ISVs) to abolish the structure which grants exclusive ownership rights of a set of data to an application. Having done that, the movement will also seek to dissolve the programmatic barricade which surrounds the once-exclusive application, and allow for the equal distribution of correlated tasks within an arbitrarily-defined computing job, to other programs non-specifically.

…

The meta-application is not an inevitable fact of computing; the marketing debacles of cross-vendor cooperation it imposes may render it as ineffective as OS/2 in changing our computing habits. Still, it is something to be wished for; and it is a far more important facet of the Windows 3 story than faceted buttons and little pictures. The way in which world industry and commerce works is not affected in the least by faceted buttons and little pictures.

Henceforth

There is good reason to believe that Windows 8 will be the last classic, all-at-once revision of the product line from Microsoft. From here on out, Windows users will be subscribers, and improvements (assuming that’s what they are) to the system will be made automatically — for most people, silently.

One of the metrics we in the technology business have used to make milestones in our lives, will cease to exist.

There was a time in the last century when refrigerators were the very symbols of the technologically advanced household, and when Jell-O symbolized the wonders of a new world — one where an everyday family could enjoy a chilled dessert without considering the expense. There were magazines devoted to the class of consumer who could afford refrigerators, and who wore their status proudly by displaying such magazines on their coffee tables. Today, refrigerators are not even particularly interesting to professional chefs whose brilliance depends on them. A fridge is a fridge. You don’t publish blogs about fridges.

So we knew it would happen sometime. A day is coming soon when folks will laugh in amazement as they recall standing in line for days waiting to buy a telephone. A PC, if it is still called that, will be a virtual appliance people use to process information and watch their media. What they watch will probably not be about the act of watching media, and whether that makes an impact on their lives, because it won’t. The degree of interest people will invest in whether their computing device comes from Microsoft or Apple will be as low as whether their dishwasher is a GE, an LG or a Whirlpool. They might not even be able to tell you if you asked. And you won’t ask, because you won’t be interested.

And yet life will go on. Kids will still learn new things about great inventions in a brighter world. Young people will be inspired to chronicle the history of their times. Great new concepts will transform the way we live, work and think. Technology will mean something else than it means today. And folks not so young any more will realize when an era has ended, by how little its passage into history makes that much of a difference.

Screenshots of Windows 1.0 and Windows 3.0 courtesy Microsoft.