Each year, the U.S. government declassifies thousands of documents and releases them to the public through collections like the Declassified Document Reference System (DDRS) and the CIA’s FOIA Reading Room. Some, however, contain “redacted” information that’s too sensitive to be released — leaving, for instance, key details of an FBI memo blacked out for the average reader.

Enter the Declassification Engine, which aims to harness Big Data analysis and some old-fashioned crowdsourcing to peer through the “black bars” of redacted documents and reveal what the government doesn’t want you to know.

Using publicly available, declassified documents as its sources, the Declassification Engine aims to eventually make informed guesses about what those black bars are hiding, providing a “word cloud” of likely possibilities. Is that blacked out word “Aurora,” for example, potentially referring to new types of advanced aircraft? And, if so, does that imply that similar redacted memos refer to the same key words?

A Tool For Historians And The Public

The Declassification Engine could be an instrument for historians and conspiracy theorists alike. For now, though, it’s basically just a set of data-analysis tools developed by researchers at Columbia University.

One finds correlations between specific words and often-classified memos, for example. Another was designed to help train the system to pick up on differences between redacted documents, and what was revealed years later when the government declassified them for public eyes. Eventually, they’ll form a more cohesive whole, the Engine’s creators say.

To take the next steps, the Engine’s founders are asking for help. Last week, historians, journalists, legal scholars, statisticians, and computer scientists met at Columbia University to formally launch the Engine — and to ask for money. The Declassification Engine hopes to raise $50,000 to fund the project, and its founders have only raised a few hundred dollars at present.

Matthew Connelly, a historian at Columbia and one of the creators of the Declassification Engine, explained that the group is consciously trying to put the Declassification Engine on the “white hat” side of the fence — the opposite side, in other words, from organizations like Wikileaks.

The Engine’s source material consists of documents that have already been declassified and released by the government for public scrutiny. Furthermore, its users aren’t “cracking” redactions; they’re simply making guesses. What they hope are good guesses, but guesses nevertheless.

How The Engine Revved Up

Declassification straddles a long-standing fault line in American politics, as Marc Trachtenberg, a professor of political science at UCLA explains:

There is thus a built-in conflict between the consumer and the supplier of historical evidence: we historians want to see the ‘dirt,’ but those responsible for the release of documents want to make sure that the material released does not damage the political interests they are responsible for protecting.

Declassified documents are often a tool to better understand our own history. But getting at that understanding sometimes requires teasing out decades-old data.

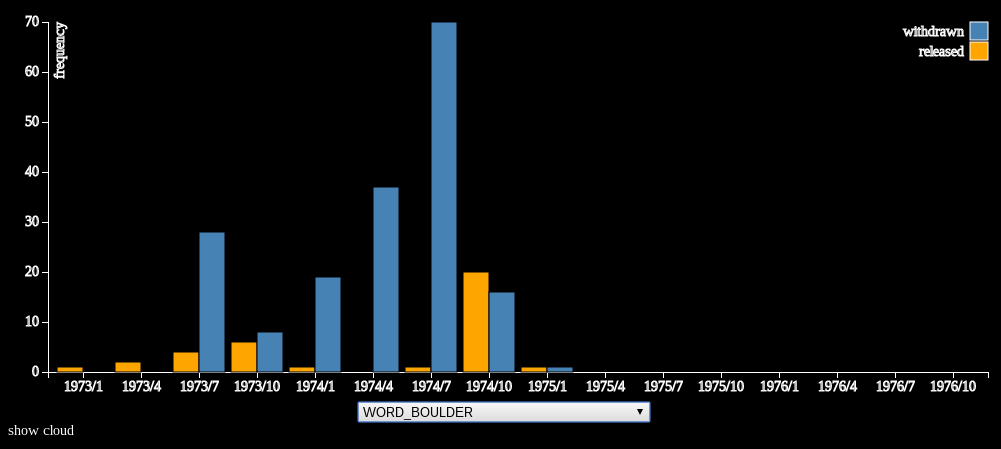

One of the first things the team did last year was to analyze which keywords were most closely associated with federal decisions to withhold documents among 1.4 million State Department cables. They then created a tool to analyze diplomatic activity over time depending on which terms were used, and the likelihood that a cable that included a specific term would still be classified.

That analysis revealed that 1970s cables that contained the word “Boulder” or phrase “Operation Boulder” were much, much more likely to be withheld, Connelly said. As it turned out, Project Boulder was President Nixon’s plan, hatched following the hostage crisis at the Munich Olympics, to increase FBI scrutiny of Arabs entering the United States. In other words, 1970s-style ethnic profiling.

In this case, Connelly said, the archive of scanned documents could have served as a historical context when people began discussing the treatment of Arab-Americans thirty years later, after Sept. 11. But without the digital archive of source documents, that context wasn’t readily available.

“The reason that these historians have never even heard of it is because the vast majority of the documents have been withheld, in the archives,” Connelly said. “Without those documents, we can’t even begin to try and derive some of these lessons.”

Is It Legal?

Given the political climate surrounding security in the decade-plus since September 11, the Declassification Engine’s creators said last week that they were somewhat nervous that the U.S. government might try to clamp down on it. (The creators, naturally, believe that it’s perfectly legal.) Connelly, however, said that the discussion during Friday’s conference gave him reason to believe that the Engine’s creators aren’t likely to face any investigation from law enforcement agencies.

Nevertheless, on Friday, the FAQ portion of the site was modified to eliminate all references to the project’s legality, including that the group sought input from the State Department and the National Archives to better understand the declassification process.

“In some cases, we are using statistical methods to predict what is still classified,” the Declassification Engine’s FAQ said Thursday night.

How The Tools Work

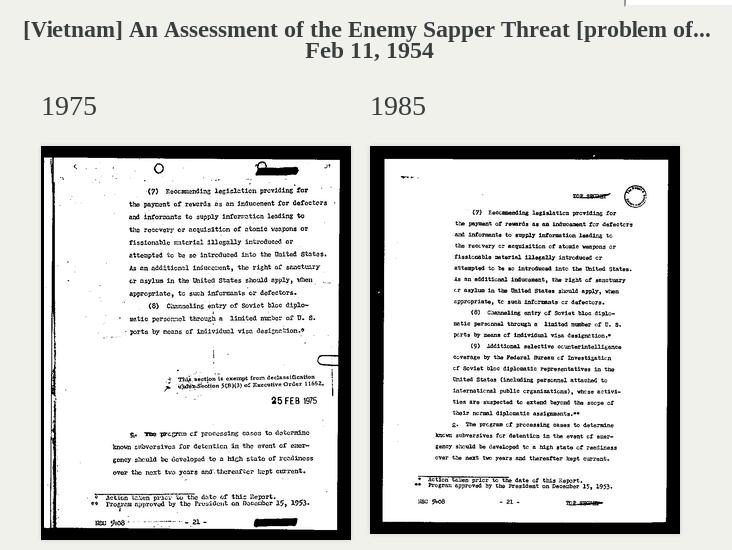

Connelly gave ReadWrite an early glimpse of one component of the Engine on Thursday night. That’s the Redaction Visualizer, which compares redacted and unredacted documents and highlights the differences. On the surface, this seems pretty obvious.

But the Visualizer is also the basic equivalent of your math homework: the redacted document provides the problem to solve, and the unredacted document is the “answer”. This supervised data will “teach the computer to teach itself about what’s in the redaction,” Connelly said.

The real work for the Engine, though, lies in deciphering the redactions themselves. And the biggest arrow in its quiver is context. In total, the Engine uses 117,509 documents from the DDRS, with the most from the Eisenhower and Johnson administrations.

The text of the documents themselves are just one part of the puzzle. But there’s a surprising amount of unredacted metadata attached to each as well: the date, the author, the subject, who classified it, when it was declassified — 68 fields in all, Connelly said. All can be used as clues to make guesses as to what the redacted content contains. Connelly admits that he’s not even clear on how well the Engine could work, once it’s up and running.

What the Declassification Engine hopes to do for each redaction is generate a “word cloud” of the words that are statistically likely to be hidden by the redaction. Granted, this is a lot easier to do with a short series of letters, such as a name or date. Still, any guesses could be used to tease out further possibilities, and cross-correlated with other, similar documents to make further guesses.

Eventually, the Declassification Engine could become a Web site, where users could upload their own declassified documents, run them against the tools, and also add their own insights. “It would create a virtuous circle, and [users] would be able to make more and more powerful and accurate predictions,” Connelly said.

Obama Turbocharges The Engine

The Declassification Engine received an unexpected boon from the Obama Administration on the eve of its launch: an executive order making machine-readable government documents the law of the land.

“Government information shall be managed as an asset throughout its life cycle to promote interoperability and openness, and, wherever possible and legally permissible, to ensure that data are released to the public in ways that make the data easy to find, accessible, and usable,” President Obama wrote. “In making this the new default state, executive departments and agencies shall ensure that they safeguard individual privacy, confidentiality, and national security.”

The order could remove the need to optically scan some government documents, allowing the Engine to more quickly process bunches of files. It remains to be seen how executive agencies will protect their electronic documents, however.

But, as Connelly noted, the order begs the question: if machines are now allowed to read government documents, shouldn’t they be allowed to guess what they’re hiding?