Guest author James King is the founder and CEO of UpDownLeftRight.

We had a brief, passionate, but ultimately tempestuous relationship. When we first met, I was excited about what the future could hold for us. I wanted to introduce it to all of my friends. I took it to meet my parents, hoping they would love it as much as I did.

I couldn’t put my finger on exactly the moment that things turned sour, but the passion started to ebb away. Little things started to irk me—too many notifications, too many little reminders. The things that excited me in the first weeks were the very things that made me want to retreat.

Self-assuredness is one of the most attractive things in other human beings. But that was the biggest problem with this device. Once you get past the shiny newness of the Apple Watch, you begin to realize that you’re interacting with a device that has no sense of who or what it actually is.

Why Wearables Need Fixing

A report from third-party analysts Slice Intelligence shows that Apple Watch sales are down 90% since launch—which is a big deal, since it implies early adopters aren’t converting more cautious buyers with word-of-mouth. It also notes that Fitbit is outselling Apple in the wearables space.

Apple may already be giving smartwatch companies like Pebble a run for their money, but its watch has failed to disrupt the larger wearable marketplace.

Is this simply a case of Apple just getting it wrong (for once), or does it point to a wider problem facing the entire “wearables” category?

Comparatively, Fitbit continues to crush it, still holding the biggest slice of the wearables pie. However, everything may not be as rosy over at Camp Fitbit as this might suggest.

In a fascinating break down of Fitbit’s IPO and S-1, Malay Gandhi at Rock Health calculated that more than 70% of Fitbit purchasers from the first three quarters of 2014 churned before year’s end. This aligns with more anecdotal evidence that many owners lose enthusiasm, as the novelty of knowing how many steps they’ve taken wears off. One research firm, Endeavour Partners, estimates that about a third of these trackers get abandoned after six months.

So what needs to change? How do we create hardware and experiences that will get people to engage and stay engaged? To get them to feel the same way about a wearable gadget as they do about their iPhone?

A Wearable Is Not A Smartphone

In reality, activity trackers and smart watches don’t actually create any unique experiences—we’re all aware, on some level, how much we’ve been moving and can get some variation of that data. In the case of a smartwatch, we get “glance-able” extension of a smartphone’s feature set, which is not destined to disrupt consumer habits on a large scale.

As the iPhone completely reinvented the “in-hand” experience, wearables needs to do something completely new with the “on-body” experience, if their makers want to make them mainstream.

The Apple Watch, for instance, seems to be a device with a distinct lack of “design purpose.” When it comes to Apple, the company may be the greatest marketing machine the world has ever seen. There has always seemed to be a tangible sense of what I call “Marketing By Design” that runs through its entire product suite. Yet, for once, even Apple seems to have no clear idea on what exactly the Apple Watch is for. That’s clear, just from the TV spots: Essentially, you just perform a limited version of all the functions available on your iPhone, but on your wrist. Not especially compelling, since the handset—stashed in your pocket—is only ever a few inches away from you.

Design For Revolutionary Uses And Services

The highly competitive fitness tracker is built around some particularly narrow usage scenarios and habits.

For a tangible example, visit any gym in the western world in early January. Visit the same gym in March, and you’ll see those numbers drastically reduced. (This may be why Fitbit is reluctant to release clear data on user retention.)

To expand the appeal of wearables beyond early adopters and “quantified self” fanatics, we need to design services and experiences that extrapolate further on the data sets these devices produce.

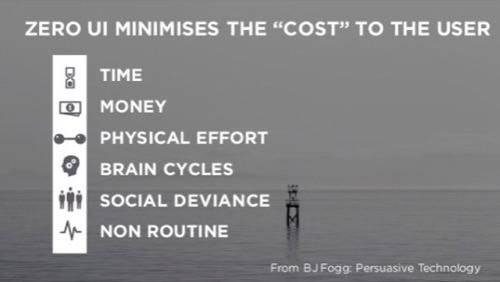

In an excellent post on Zero UI, my old colleague at Fjord, Andy Goodman, said:

Zero UI refers to a paradigm where our movements, voice, glances, and even thoughts can all cause systems to respond to us through our environment. At its extreme, Zero UI implies a screen-less, invisible user interface where natural gestures trigger interactions, as if the user was communicating to another person. The replacement of these monolithic screen-based devices by ambient technology that surrounds and immerses us is being driven by Living Services. In the end, this could be a very good thing because social interactions could become more natural again – and not as obviously mediated by devices. Our attention could again return to the people sitting across the dining table, instead of those half a continent away.

With this in mind, we need to focus on designing wearables for the scenarios of the future—not reference, imitate even, the experiences and designs of the past. Devices that provide immediately useful data and metrics, but then simultaneously look to execute these in revolutionary frameworks and systems that look to the future of an integrated world, say, built on the Internet of Things (IoT) and “Living Services” (see below). They will prevail, not only in the short term, but also in the long term as scalable, industry-defining platforms and businesses.

One of our investors, Mark Curtis (also a fellow Fjordian) has provided fascinating insight on “liquid expectations” within “living services.” Living Services are the result of two powerful forces: the digitization of everything and ‘liquid’ consumer expectations. They respond by wrapping around us, constantly learning more about our needs, intents and preferences, so that they can flex and adapt to make themselves more relevant, engaging and useful.

Consumers demand this now as the standards are being set by the best of breed across the entirety of their experiences, not restricted by sector—hence liquid expectations. Indeed, I believe the companies that will lead the charge in the wearable sector will look to define those “expectations”.

We must blur the lines between rapidly established verticals. The IoT space is currently overly focused on the hardware that will make up this connected ecosystem. While we, of course, need to lay out the infrastructure for IoT, we also need to rapidly focus on the key agents in this system: the users.

While embeddable and even ingestible devices may come into prominence in the future, the best tools for indexing the user, and providing identity in a connected world, are the wristbands and smartwatches of today.

Low-impact devices can act as the central interface terminal for all our interactions with services, experiences and things. Meanwhile, gestures will play a huge role in the development of Zero UI. Fitness trackers and smartwatches—with their plethora of gyros, accelerometers, and magnetometers, coupled with their position on the body—are the best positioned to do this.

The way forward, to finally fix wearables, seems as clear as the watchface that used to be on my wrist.

Images courtesy of James King