It hasn’t been a good week for HP. On the back of lower-than-expected earnings, the tech titan also announced it would cut between 11,000 and 16,000 employees. Sadly, HP is in good (or bad, if you wish) company. Oracle has missed estimates more often than it has hit them the past few years, most recently missing third-quarter earnings. IBM, for its part, hit earnings but missed its revenue targets. Again.

Clearly, the legacy IT vendors are struggling. But just as clearly, technological innovation is not. It’s just being developed and deployed in ways that challenge the very foundation of yesterday’s technology businesses.

Today’s Software Isn’t Licensed—It’s Driven

To get a sense for what I’m talking about, take a look at a recent edition of The Wall Street Journal:

While HP’s bleak outlook gets the biggest headline, up in the far right is a reminder of just how well the new breed of “technology vendors” is doing.

Uber, chasing a potential venture capital round of $500 million and a valuation of $12 billion, isn’t a technology company, though its legal name is Uber Technologies Inc. It provides a service that matches available drivers to people in need of a ride. Yes, that service depends upon Node.js, Python and a range of other open-source software, but few would classify Uber as a technology company, at least not one in the same vein as an HP or SAP.

After all, Uber doesn’t sell technology. It sells a technology-based service.

The same is true of many other companies that depend heavily on technology but aren’t “technology companies,” per se. Google (advertising), Facebook (social networking), Amazon (um, everything), Netflix (entertainment) and many others all point to a trend captured three years ago by Marc Andreessen: Software is eating the world.

As Andreessen wrote:

More and more major businesses and industries are being run on software and delivered as online services—from movies to agriculture to national defense. Many of the winners are Silicon Valley-style entrepreneurial technology companies that are invading and overturning established industry structures. Over the next 10 years, I expect many more industries to be disrupted by software, with new world-beating Silicon Valley companies doing the disruption in more cases than not.

Over time, it is likely that Uber will get bigger headlines than HP as technology-fueled services become the norm for an industry that has depended for too long on cumbersome licensing strategies and expensive maintenance contracts.

Does Software Stand A Chance?

Are software companies doomed? Mostly, yes. While large enterprises persist in wanting to install and run software in data centers behind their firewalls, approximately none of them love the current enterprise sales model that has them dickering over massive discounts on overpriced license and maintenance contracts.

So a new breed of software vendor is rising.

While more software will move to a software-as-a-service model, both on the infrastructure (Amazon Web Services) and application (Salesforce.com) side, there will also remain companies like Red Hat. Red Hat now makes more than $1 billion each year selling services around Linux, JBoss middleware and more. Red Hat doesn’t sell software. It never has.

Instead Red Hat gives away its software—all of it—under an open-source license. It makes money by selling an update service (Red Hat Network) that keeps the software patched and production ready, as well as support and ongoing certification of a host of third-party software that runs on or with its software. In the wake of the Big Data movement, we’re seeing vendors like Cloudera and Hortonworks achieve serious scale, growing up to challenge their more traditional peers.

But even they aren’t the biggest winners.

Every Company A Technology Company

Ultimately, as Cowen & Co. analyst Peter Goldmacher posits, the greatest financial beneficiaries of software aren’t those selling software at all, or even those selling SaaS offerings based on underlying open-source components. At least in the Big Data world, he argues, the biggest winners are those companies that have the necessary technical talent to use software to channel the value of data.

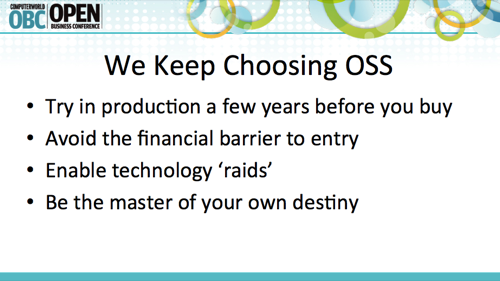

At Uber, this means doing “crazy math and science” to connect drivers with riders and establish estimated pick-up times. At old-school retailer Sears, it means leveraging new-school Hadoop to deliver personalized coupons and other marketing collateral to drive sales. And for your company it will undoubtedly involve other foundational technologies, much of it open source for reasons expressed by Zohar Melamed in his Open Business Conference keynote earlier this month:

None of this bodes well for the technology incumbents, of course, but it bodes very well for the future of the software industry. It will become increasingly difficult to categorize and far more potent. That’s a trade-off worth making.

Lead image by Flickr user Ken Funakoshi, CC 2.0