When Microsoft premiered Silverlight as something called WPF/E in 2007, it was with the idea of enabling developers to build “rich Internet applications,” and to conceivably run them outside of browsers, and on platforms other than Windows. The “A” in “RIA” stood for “applications” – the full word, the complete class that also includes data-intensive programs such as Word, Outlook, and Photoshop. Yet such applications required full access to the file system, which was not possible given the limited trust relationship that must exist for a remote application triggered from a browser.

Over four years later, Silverlight finally has perhaps its single most requested feature. Called P/Invoke, short for “platform invocation,” it’s a system that enables an application to deploy itself remotely, and then implement the safeguards required for it to elevate its own privilege to that of an installed application. Silverlight 5 is finally here, and if you’re wondering why you can’t hear the fanfare, it’s not because HP open-sourcing webOS has drowned it out. It’s because, although Microsoft isn’t saying so formally today, S5 is probably the end of the line.

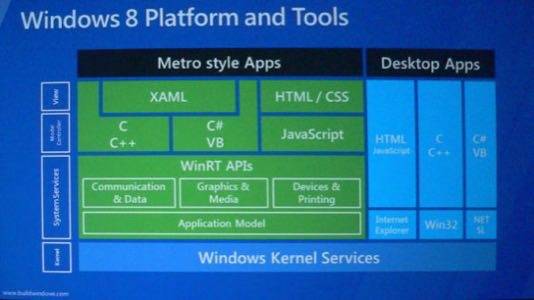

In this diagram of projected system resources for the forthcoming Windows 8, Silverlight is mentioned as “SL” in the very lower right corner. And as Microsoft’s updated Support Lifecycle Policy for all versions of Silverlight now states, the company pledges to continue to support S5 just like its predecessors.

The story this diagram fails to tell, however, concerns how the two styles of apps address system resources. As Microsoft currently envisions it, apps build for the Windows Runtime (WinRT) do not have the level of unrestricted access that has just been made available today in Silverlight 5.

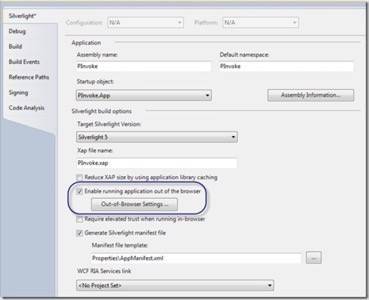

The way S5 works now, when a developer is building an application that requires full access to kernel resources, including the file system, he checks a box in Visual Studio that sets the option at compile time for requesting elevated privilege on the client side. He doesn’t have to make adjustments to the code; instead, certain instructions that might have been prohibited (such as importing the kernel32.dll library) suddenly become allowed.

Another key feature for true application functionality that P/Invoke makes possible is multiple windows within a window (what the Windows OS used to call “MDI”). Excel works this way now, with a workspace that can be inhabited by multiple documents (Word used to work this way, but changed with Office 2007). In the Windows OS, individual windows have their own contexts, so a remote app generating multiple windows triggered from a browser would have to establish a kind of cross-trust relationship that would be theoretically dangerous.

With S5, the privilege elevation process uses the User Account Control resources that premiered in Windows Vista. This way, elevation takes place only with human assistance, and a browser-based app cannot obtain high privilege on its own.

By contrast, Metro apps at present have limited access to the file system. A remotely-installed Metro app can create its own directory for storing user data, which for Windows 8 will be located in the AppData folder. A limited number of so-called file picker objects will be made available for specific functions, such as choosing pictures for use as avatars. Alternately, in the manifest for each Metro app (a kind of contract which the OS must approve on an app-by-app basis), an app can declare its intention to access the current user’s own libraries (groups of homegroup-accessible folders declared together for a common purpose, such as Pictures or Music) or the system’s public libraries.

Microsoft engineers tell me that apps really don’t need more access to the file system than this limited access provision. One exception I can foresee involves intensive games, which may need access to shared resources outside the game programs themselves. Silverlight 5 now includes access to Microsoft’s existing XNA game libraries, enabling developers to deploy rich 3D games using the same graphics libraries once relegated for use with the full .NET Framework.

So there are some foreseeable circumstances where Silverlight 5 can provide specific functionality over and above what’s currently foreseeable with WinRT. But this is not the message that Microsoft’s Developer division began giving developers in September. Repeatedly, we’ve been told that WinRT is the way “forward,” using that specific word, and executives as high up as Windows division president Steven Sinofsky have characterized “forward” as beyond Silverlight. And we’ve noticed that while Microsoft executives historically gave us some degree of insight (more than just hope) into future Silverlight versions as much as two releases ahead, today we’re hearing literally nothing about a “Silverlight 6.”