Two weeks ago, a security researcher set off an intentional firestorm over the discovery of data that seemed to indicate a flaw in the way cryptographic systems using “multiple secrets” (more than one key) protect a session. Since the report of that discovery was published, experts have claimed its author may have reached an unsubstantiated conclusion.

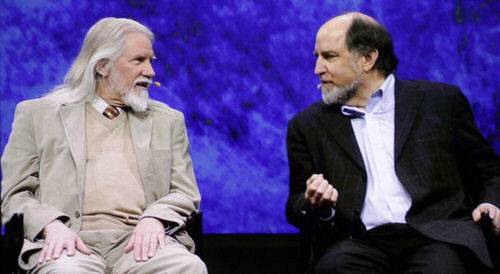

In any event, yesterday at the RSA Security conference in San Francisco, the man the report’s very title praised for being “right” all along – cryptographic pioneer Whitfield “Whit” Diffie – told attendees that if a problem actually does exist, its solution may be deceptively simple.

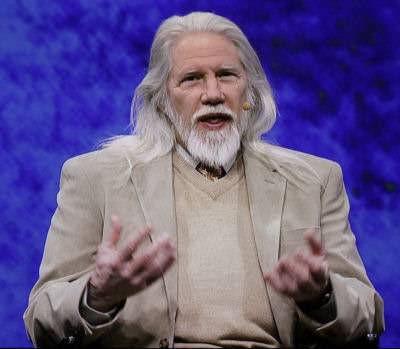

The problem, as the report “Ron was wrong, Whit was right” indicated, was that a substantial percentage of generated RSA keys contained common factors, thus rendering them ineffective or untrustworthy. “That seemed very serious to me, and sort of a phenomenon unique to RSA,” Diffie told a packed keynote session. “And eventually I realized – and as I thought about it for a week, it’s come to seem just as charming, but as a practical matter, much less serious than it did to start with, but something that probably does need a bit of addressing.”

Diffie noted, with perhaps a hint of sarcasm, that the report’s authors – who included Swiss professor Arjen K. Lenstra – avoided sensationalism by refraining from alleging that RSA keys had been “cracked.” But he posited that what Lenstra’s data could actually be indicating is a flaw in as few as one bad random number generators. “It seems unlikely that two independent prime random number generators are going to be producing the same 500-bit primes.” He then expressed skepticism at the idea that one person’s key could be compromised by someone else, simply by virtue of that person holding a key generated by a common factor – when that fact is not automatically made evident to either party.

“But the fact is, if you manufacture your key material correctly – that is to say, you’re very careful about production testing of your own random numbers – this is simply not going to happen to you,” he said. “If you adopt a random number generator that has whatever this fault is, you might get this effect.”

To help improve the system, Diffie suggested it might be necessary to “out” the bad random number generators. “So my notion is, why don’t we just publish hash codes for all of the primes selected to go into keys? As a matter of fact, you might publish hash codes for all of the keys that you’ve selected for any purpose… and then anytime you generate one, if you see that it’s already in the database, you know two things immediately: One, you probably have the same random number generator they did. Two, it’s no good.”

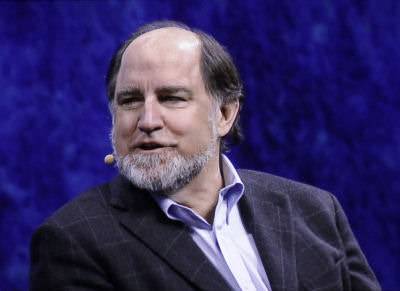

At that point, Diffie turned to the fellow that Prof. Lenstra called “wrong,” who was seated to his immediate left: Ron Rivest, the “R” in “RSA.” “I think if I get a chance to referee the paper, I’ll suggest a change of title,” Rivest said. “You are often right, and I am sometimes wrong.”

Switching back to serious mode, Rivest suggested that behind the firestorm in the report, there really wasn’t much substance. He noted a much earlier work in 1996 by Adam Young and Moti Yung on cryptovirology – the intentional creation of deceptively secret and malicious software, often for extortion. A maliciously bad random prime number generator could theoretically be written, Rivest said, so that the public key may be computed in such a way to reveal the corresponding secret key to an adversary. “I don’t think we’ve paid enough attention to that possibility,” he remarked, noting the much more serious prospect for damage.