Taking the stage at the Open Business Conference, Red Hat CEO Jim Whitehurst opened the event with a provocative question: is the industry’s choice to go open… or die? Whitehurst clearly has a dog in this fight, given that his company is the first open source vendor to reach $1 billion in annual revenue. But he laid out a compelling argument that enterprises no longer choose between competing technology products, but instead must decide between competing innovation models.

And in Whitehurst’s mind, there’s only one real choice to make: for open data, open source, open APIs.

From Vendor-Led Innovation To User-Led Innovation

As Whitehurst argues, commoditization of technology changes the way innovation occurs, moving from vendor-led to user-led. This is the natural progression for any industry, as he highlighted by referencing the automobile industry. While the companies that make engines and steering wheels are unquestionably important, we don’t really think about them much. Instead we focus on Toyota, Ford, Volkswagen, etc. as the companies really driving innovation in the automobile industry.

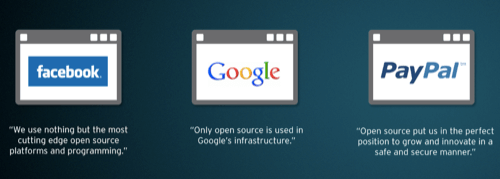

We have seen this play out in technology, With the Web giants driving innovation in mobile, cloud and Big Data. Each of the major Web companies not only uses open source, but depends fundamentally upon it:

This isn’t where open source started, of course. Open source started with existing categories, commodifying well-known categories like operating systems (Unix->Linux), databases (Oracle->MySQL), application servers (WebLogic->JBoss). But a funny thing happens on the way to the market: as more users get involved, they started to move at a faster cadence than any vendor can. Indeed, as Whitehurst noted, open source got to a point in a number of categories where it wasn’t merely replicating the state of the art, but advancing the state of the art.

As such, enterprises no longer pick products. They pick innovation models.

Picking Innovation Models

By choosing an open model, enterprises necessarily make the choice to participate in the future, rather than simply accepting the technologies their preferred vendors hand them. In such a model, even vendors must collaborate with communities, rather than dictate to them. For example, Red Hat can’t provide a long-term roadmap because it works collaboratively with the wider community of open source technology users, and can’t impose its will on that group.

Nor is open source merely a matter of ones and zeroes.

Whitehurst said he had asked the CTO of a major Web company why the company insisted on contributing its internally-developed software to the broader open-source community. The response: “If there is anything we can do to make a data center run more efficiently and hence save energy, for example, we have a moral obligation to the world to contribute it back.”

While this moral element of open source isn’t universally shared, it remains a strong motivator for a significant segment of the developer population.

Who Is Ready For An Open Future?

Not everyone wants to assume such moral obligations, and not everyone wants to give up control to a community. While we’re unlikely to see the death of proprietary software anytime soon, we certainly seem to be witnessing a move toward open innovation. Is the future as cut and dried as Whitehurst hypothesized?

Please share your thoughts in the comments.