No one but patent trolls—entities seeking to profit from patents they don’t actively use in making products—likes the current US intellectual property regime. Inefficient and outdated, the US patent system, in particular, frustrates innovation more than it fosters it.

Things may be on track to get change, Red Hat CEO Jim Whitehurst told ReadWrite in an interview. As Brazil, Russia, India, and China—the BRIC economies—boom, they will begin to exercise a profound influence over IP, even in established markets like the US or Western Europe.

It’s just not clear if they’ll change it for worse or for better.

The Best Defense Is … A Good Defense?

Sadly, while no one seems to love the current US patent regime, everyone feels compelled to participate. It’s like we’re reliving the nuclear arms race.

Even Red Hat, an open-source software company whose explicit policy is that “software patents generally impede innovation in software development” and “are inconsistent with open source/free software,” actively acquires patents, though it argues (as does most everyone else) that its patents—550 issued with another 1,200 patent applications pending—are purely for defensive purposes, to protect it from lawsuits rather than pursue other companies in patent litigation.

Explaining this inconsistency, Whitehurst argues that “as a public company we have no choice but to act within the broken patent system to protect our customers and the open-source communities in which we operate.”

Whitehurst further avers that “when we’ve settled patent disputes, we’ve never just settled to protect Red Hat and our customers, but also have ensured we simultaneously protect the open source communities that might have been impacted by them.” (The Firestar settlement is one example.)

Keeping Defensive Patents Defensive

Fine and good, but how does a company like Red Hat keep its defensive patents defensive? Given that every public company is ultimately only a hostile takeover away from losing control of its patents, is there actually any way to acquire patents with real assurance they won’t be used offensively in litigation?

While not completely airtight, Whitehurst’s response is better than most. Red Hat’s patent promise precludes a successor from asserting Red Hat’s patents with regard to open-source software, at least as to the functionality of the software that existed at the time of the acquisition of Red Hat. At that time, the acquirer could prospectively revoke the patent promise.

Fading American Influence

It’s a good attempt to minimize harm from Red Hat’s patents, but it may eventually matter far less than it does today. That’s because, as Whitehurst notes, there’s no guarantee that the US patent system will continue to guide the technology industry.

Intellectual property is simply an opinion, Whitehurst asserts. It’s a policy that we use to try to maximize innovation. But because it’s merely policy—government policy—and not some objective truth implanted on our brains by the cosmos, there’s no reason to think that other governments won’t disagree with the US approach. For example, in India software is not patentable. Different governments provide different opinions on what IP means.

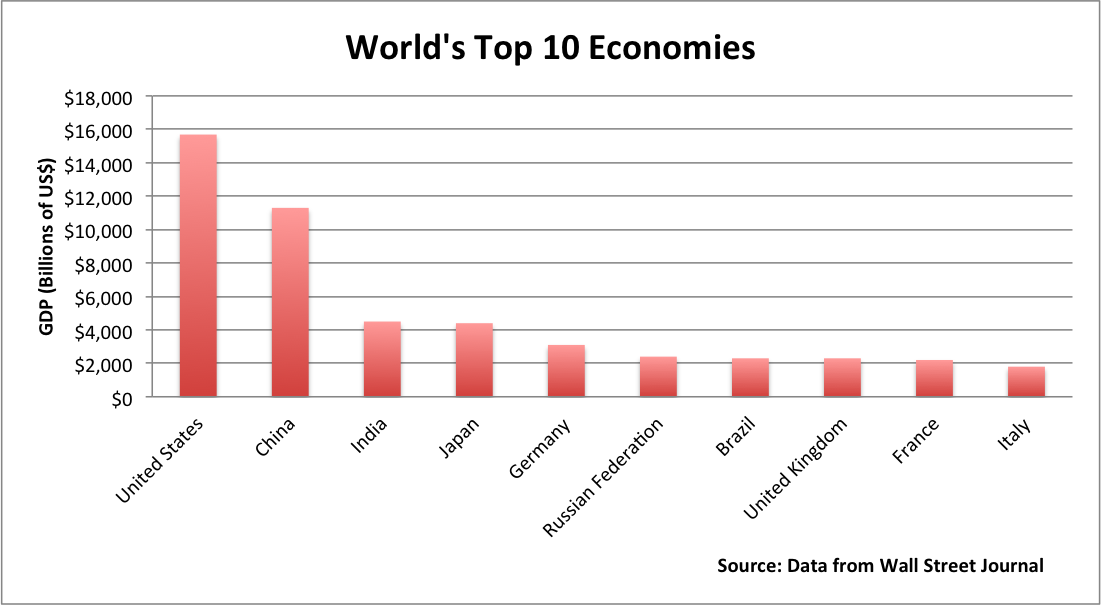

This hasn’t mattered very much to date because US consumption dwarfs that of other countries. She who has the biggest economy wins, and can dictate IP law to any who wish to do business with her. But as other countries become larger consumers, their opinions will start to matter as much as ours over the long run.

Ready For Chinese Patent Law?

Consider, for example, the relative annual growth rates of various economies. China and India are on a relative tear compared to the US and Japan:

- China: 7.5%

- India: 4.8%

- United States: 1.4%

- Japan: 0.9%

Which means that while the US still consumes more than any other company, and hence gets to call the shots in IP policy, that may not last:

According to Whitehurst, it’s not at all clear whether this trend will lead to more stringent or more open IP laws. Some countries believe that IP helps grow their economies, while others think it hurts them. China, for its part, has essentially modeled its IP regime on the US, while Brazil and India favor open source and are more likely to say that IP should be shared.

In sum, it’s too early to tell whether we’ll end up with a better or worse global IP system. The only thing we can say with some certainty is that the growing economic clout of the BRICs will impose significant changes. As Whitehurst points out, we’re already seeing this in how different IP regimes have ruled in the ongoing legal spat between Apple and Samsung. Expect this to get a lot messier over time.

Image courtesy of Shutterstock.