Never underestimate the miniscule, $35 Raspberry Pi. Although it’s marketed as an experimental machine aimed at helping you learn to code, there’s nothing entry-level about its capabilities.

In a pinch, you can even use your Raspberry Pi as a Web server. You can host a simple site or store files in the cloud so you can access them at any time—no monthly hosting fees, limited templates, or other barriers to your creativity.

See also: 12 Cool Projects For Your Raspberry Pi

Why do you need a server? The trend has been against running your own hardware and instead storing files and running programs in what’s called “the cloud”—someone else’s servers, to which you connect over the Internet.

But a server’s a server, whether it’s on your desk or in a datacenter. At its most basic level, a server is a combination of software and hardware that responds to requests across a computer network in order to provide services. The computer network could be as small as your home network or as big as the World Wide Web.

In the case of a Web server, the Raspberry Pi responds to requests to serve up Web pages, which can be simple HTML or sophisticated Web-based apps.

Because it requires little electricity and you can keep it running indefinitely, a Pi makes a great server. At my house, my two Raspberry Pis are both running as servers. One is a print server and also runs my virtual private network, or VPN; the other is a Web server. Pis are good at multitaking: I used one of my servers to wire up my fish tank so my fish could send me text messages.

Dos And Don’t Of A Pi Server

My Pi Web server hosts a single Web page that connects to a MySQL database, which in turn gets its data from a Python program, which in turn is getting data from a smart thermometer—and all of that is being hosted on the Pi. That sounds kind of complicated, but the setup shows you can seriously do a lot with something as small as a Pi.

See also: Building A Raspberry Pi VPN Part One: How And Why To Build A Server

This project is a good candidate for a Pi Web server because it is very low traffic. I’m hosting a resource that I plan to check from time to time, but that won’t be of much use to other people.

I can’t emphasize this strongly enough: A Raspberry Pi Web server is not a business solution. There are a few different reasons you don’t want to host a highly trafficked site.

The first reason is that Raspberry Pi is still not as powerful as your standard home PC. If I shared a link to my own Pi Web server in this article for ReadWrite readers to view, it’d probably crash. And since it’s connected to my own home network, I might not be able to get on the Internet myself because of all the traffic!

The second reason is that, mostly for the scenario listed above, your Internet service provider probably won’t allow it. My ISP, Verizon, even has a section where it mentions hosting your own server:

“The Service is a consumer grade service and is not designed for or intended to be used for any commercial purpose… For example, you may not provide Internet access to third parties through a wired or wireless connection or use the Service to facilitate public Internet access (such as through a Wi-Fi hotspot), use it for high volume purposes, or engage in similar activities that constitute such use (commercial or non-commercial)… You also may not exceed the bandwidth usage limitations that Verizon may establish from time to time for the Service, or use the Service to host any type of server.”

I’m definitely skirting the rules by hosting three different servers with my wireless network, but the fact that they’re all for personal use instead of commercial is probably the reason Verizon has turned a blind eye. A friend with a server hosted over Verizon had the same response: “They only sent me a warning when I set up an email server, since [Verizon] thought it could be used to send spam.”

So hosting a commercial or business site is out of the question. That still leaves personal resources open; sites and storage spaces designed for your own use. Like my Web server, which lets me monitor activity in my home aquarium even when I’m not there.

For this tutorial, let’s forget about databases and sensors—you can read about the details of how I handled those in my earlier piece—and everything but the HTML. I’ll show you how to quickly and easily build a home on the Web, hosted on Raspberry Pi.

Setting Up The Pi

Your Pi isn’t ready to host a website right out of the box. First, it needs three things from you:

- A router and modem. It may seem obvious, but you’ll need a router and a modem from your Internet service provider. Even though you don’t have to pay for Web hosting, you still have to pay for your Internet connection. You may have gotten just one box from your ISP, but usually that’s a router and modem built into one device. A separate router will give you more flexibility to connect multiple devices.

- An Ethernet cable. Or, less recommended, a wireless USB adapter. Either way, you’ll need the Pi to have a permanent Internet connection.

- An operating system. I recommend Raspbian. In order to set up an operating system on your Pi for the first time, look at my tutorial.

- SSH (Secure Shell) access. A Web server doesn’t need a keyboard, monitor or mouse. Instead, you’ll access the Pi remotely through your laptop or another device that has those things. Here’s my tutorial on how to set up SSH for the first time.

Setting up Internet access, an operating system, and SSH are necessary first steps for a number of cool Raspberry Pi projects. It’s a good idea to get used to doing these three things every time you unbox a new Raspberry Pi.

Finally, let’s make sure everything is up to date:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get upgrade

This will refresh the Pi’s knowledge of its packages and their dependencies. If you’re trying to install a package (like Apache, as we will in a minute) this will prevent the Pi from frustratingly being unable to locate where the latest version of the package is stored online.

Installing Apache

How do you turn a Pi into a machine capable of hosting websites? You do what other server maintainers have been doing since the earliest days of the Web—you install Apache Web server software.

When I say Apache is a Web server, I mean it’s a program that listens for server access requests from Internet browsers and grants them if permitted. So if you want anyone to be able to access a website on your Raspberry Pi—including yourself—you need to install a Web server.

The name is a play on “patchy,” since its creators were always patching the software to fix problems. It’s gotten a lot better since those early days, though. Apache is a free, open-source HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) Web server application. When you type a URL into your Web browser, a Web server somewhere replies by serving up a Web page. Apache is popular for these purposes: Roughly 50 percent of sites are hosted by servers running Apache.

Fortunately, this is a one-step process. Go to the command line and type:

sudo apt-get install apache2 php5 libapache2-mod-php5

This prompt accomplishes several things all at once. It installs the latest version of Apache, the server we need to use. It also installs two other packages: PHP and a library that helps Apache work together with PHP.

For a basic HTML site that remains static and doesn’t have many features aside from text, you do not need PHP. But if you ever want your site to connect to a database, you’ll need a web framework. PHP is a Web framework that adds more functionality to basic HTML websites.

For example, if you wanted to install WordPress on your Raspberry Pi hosted site, you’d need to make sure you could install at least one database.

When Apache is finished installing, restart it with this command to activate the program:

sudo service apache2 restart

Making A Basic Website

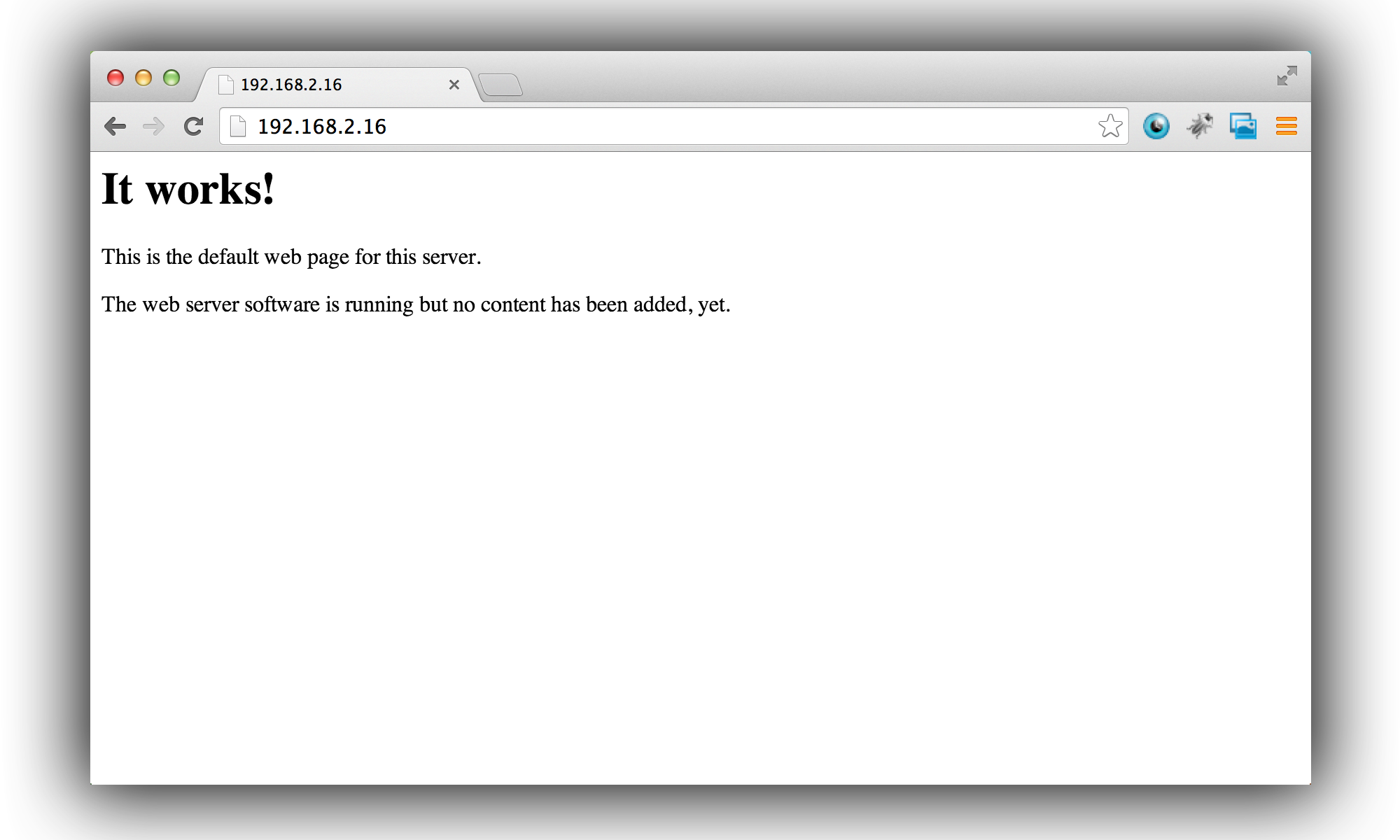

As soon as the Raspberry Pi finishes processing the above command, it instantly generates a basic, working website.

Go to your Web browser and type in your Pi’s local address. This will look something like 192.168.X.X. (If you haven’t obtained that address already, see my instructions on using the sudo ifconfig command to get it.) A very basic site should appear, headlined with the phrase, “It works!” This simple index.html page came preinstalled along with Apache.

Want to tweak it? Visit the index.html page on your Pi:

cd /var/www/

sudo nano index.html

Try changing the words around, saving the file, and navigating back to the Pi’s local address again to watch your changes take form.

Getting It Online

You can access and edit your website, but it’s only visible to you on your local network. That’s a good thing—you don’t want it to be this easy for people to access the Internet in your home!

See also: 5 Pointers To Supercharge Your Raspberry Pi Projects

So how do you get your Web server on the actual Web, not just your local network? Think about the way the Internet gets into your home. Your ISP gave you a box that serves as the router. When you access the Internet, your request goes through your router to the Internet, and then back through the router back to your computer.

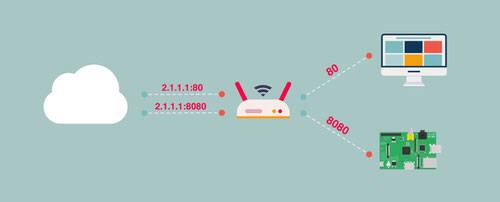

More technically, the ISP is sending the request back to port 80, the default port for HTTP requests. Or as we know them, Web-browsing requests.

Our goal is to have requests come from the Internet and go through the router to our Pi.

The problem? We’ve got lots of devices at home—computers, tablets, cell phones, to name a few—aside from the Raspberry Pi. Trying to direct traffic to just the Raspberry Pi, out of all your devices on the network, would be like sending a letter to a person who lives in an apartment complex without specifying the apartment number. The mail would be returned to its sender.

And that’s not the only problem. We’ve got to consider that in many cases, the router comes equipped with a built-in firewall, a security system that controls inbound and outbound traffic. Usually, the goal is to not have people from the Internet access your home network. But this time, we want to punch a Raspberry-Pi-shaped hole in the firewall for traffic to get through.

Luckily, there’s one solution to both problems: we forward port 80 to something else. If we say the Raspberry Pi is at, for example, port 8080, the router will forward the traffic there.

In my examples, the numbers 2.1.1.1 are just mimicking the numerical pattern of URL requests. Usually, you request a URL by typing in a domain name; this is just how the computer reads it. We’ll go over converting our IP addresses into human-readable domain names in a few more steps.

A Forwarding Order For Your Pi

This next step will depend on the type of router you have, and may differ depending on that particular router’s software.

Here are some port forwarding tutorials for major router manufacturers:

This is the most independent part of the tutorial, so you might be asking yourself, “What happens if I skip this and just assign a domain name to the Raspberry Pi’s IP address?”

I tried this and it’s possible. But don’t expect your ISP to allow it for very long.

Just for kicks, I tried skipping the port forward and applying a domain name to my Raspberry Pi’s IP address. Since I could identify its IP address as unique from the other devices on my network, there should be no problem, right?

Wrong. My ISP, Verizon, blocked access in fewer than 60 seconds. That’s probably because it judged that I was doing something unwise. I warned you earlier that your ISP will forbid activities that it thinks are against its terms of service.

When malicious bots crawl the Web, sometimes they’ll ping port 80 by default, just to see if they can get access. In response, some ISPs will block inbound traffic to port 80 by default. Verizon didn’t want me to make a website accessible at port 80 because it’s the standard. When using any other port, however, Verizon hasn’t given me any trouble.

Getting Yourself A Domain Name

Now, people can access your site from anywhere—if they know your Raspberry Pi’s external IP address. But most people are accustomed to writing a domain name request in actual words.

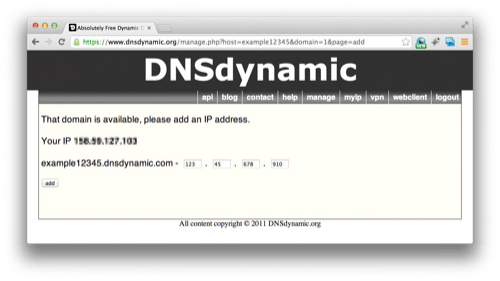

Fortunately, there are free services you can use to translate your IP address into a domain name. I use DNSdynamic most frequently, so my instructions will reflect that service.

Sign up for DNSdynamic, and secure an available domain, which will look something like “Example.dnsdynamic.com.”

DNSdynamic will helpfully tell you your current external IP address. I’ve blurred mine out for safety; you don’t want to share this with people. But instead of your own IP address, you’ll want to fill in the Raspberry Pi’s external IP address, which you’ll have secured after the port forward.

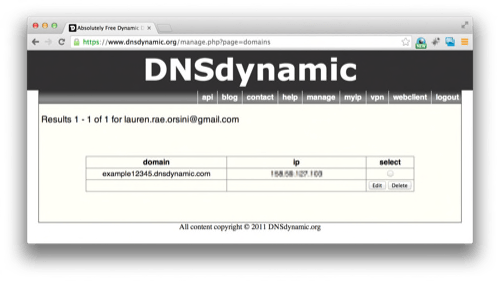

Now you’ve got a human-readable domain name that forwards to the Pi’s IP address.

And you’re done! Share your domain name with friends or family or anybody you’d like to be able to access your site. Just don’t get too popular—because if your Pi gets too much traffic, you’ll have to do some explaining to your ISP.