For decades the enterprise software industry has grown fat on outsized, upfront license fees coupled with ongoing, high-margin maintenance streams. Cracks in the model have threatened to dismantle the system for years, as reported by The Wall Street Journal back in 2009, with CIOs chafing at paying for low-value, high-cost maintenance.

But if Oracle’s big earnings miss last week is any indication, one of three disappointing quarters over the past two years, the cracks have widened to a chasm. As bellwether for the enterprise software incumbents, Oracle’s miss suggests that the legacy vendors may struggle to adapt to the world of open-source software and Software as a Service (SaaS) and, in particular, the subscription revenue models that drive both.

It isn’t going to be pretty.

Changing How Vendors Get Paid

This isn’t just a matter of improving legacy software products. It’s a matter of fundamentally changing how these legacy vendors deploy and charge for software. For example, Oracle’s entire cost structure is built around the premise of a hefty upfront license and high-margin maintenance (Over 20% of the license fee). Ever read The Innovator’s Dilemma? Clayton Christensen’s classic addresses just this sort of inability for established companies to change. It turns out to be brutally hard, and often impossible.

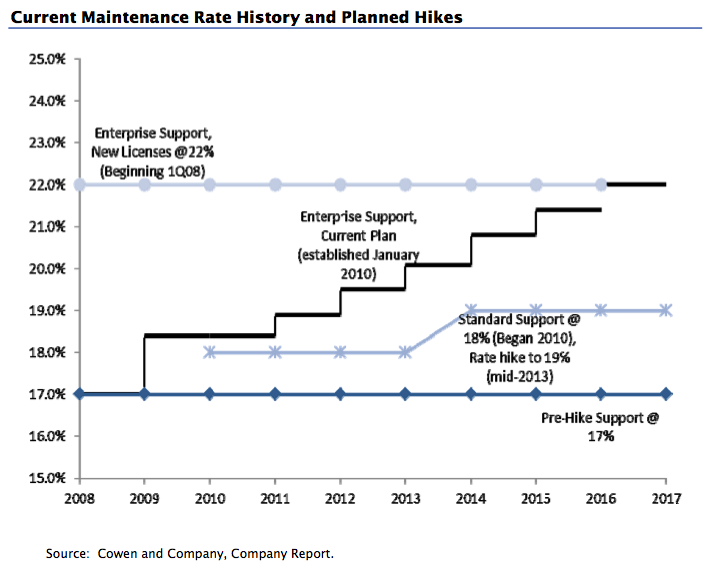

Small wonder, then, that SAP has been raising its maintenance fees, trying to milk more money from its customer base as it faces serious headwinds maintaining its license model against upstart competitors like Workday:

Such actions basically force customers to start looking elsewhere, if they weren’t already.

If this were just a matter of technology, Oracle, Microsoft et al. would likely weather the storm quite well. Oracle makes great software. There’s a reason it’s the enterprise database leader, and by a wide margin (though smaller rivals are gaining in popularity).

But building great technology is not enough. Oracle’s peers, from SAP to IBM to Microsoft, also charge for software in this way, and across the industry they’ve been taking a beating as enterprises look to the improved productivity and OpEx of open source and SaaS. Oracle, for its part, blamed its miss on “sales execution,” but as Cowen & Co. analyst Peter Goldmacher points out,

…[W]e have a hard time believing that almost all the legacy software names are suffering from poor sales execution at the same time. We believe the primary issue is a fundamental shift in the technology landscape away from legacy systems towards a new breed of better products at a lower cost both in Apps and in Data Management. Virtually every emerging software trend is having a deflationary impact on spend.

Not everyone sees it this way. Wells Fargo senior analyst Jason Maynard urges investors in Oracle to “keep calm and carry on,” and expects Oracle’s license revenue to grow 5% year over year.

Good luck with that.

Developers Rise In Importance

The problem isn’t that Oracle and the mega-vendors have lost their hold on CIO affections. They haven’t. The problem is that they have little to offer enterprise developers, who increasingly are the gateway to software adoption. Explaining this shift in his excellent The New Kingmakers, Redmonk analyst Stephen O’Grady argues:

With the rise of open source…developers could for the first time assemble an infrastructure from the same pieces that industry titans like Google used to build their businesses — only at no cost, without seeking permission from anyone. For the first time, developers could route around traditional procurement with ease. With usage thus effectively decoupled from commercial licensing, patterns of technology adoption began to shift….

Open source is increasingly the default mode of software development….In new market categories, open source is the rule, proprietary software the exception.

The top-down approach, in other words, is losing its currency within the enterprise, as both open source and cloud enable developers (not to mention line of business executives) to get work done without getting permission.

The effect on the mega-vendors is overwhelmingly negative, as Oppenheimer analyst Brian Schwartz posits:

We believe something more secular is occurring as cloud computing increasingly entices CIOs to refresh their legacy IT systems with cloud services rather than infrastructure. Additionally, software purchasing is becoming more decentralized with decision-making power shifting away from IT and weakening the selling advantage as a “one-shop supplier.” These trends dampen big-ticket on-premise software purchasing and remain a headwind for the infrastructure vendors.

None of which means the big vendors are going out of business anytime soon. In my years at Novell, for example, I witnessed a serious decline in the company’s fortunes, even as revenue remained above $1 billion.

Time To Change?

In fact, Novell is a great example of what might happen to the mega-vendors. Ultimately, Novell had to be bought out and then split into pieces in order for its SUSE business unit, now an independent company, to thrive. SUSE can now support its subscription model without all the overhead Novell’s legacy business imposed on it.

The same may well prove true for the other enterprise mega-vendors.

Not all enterprises will be affected equally, of course. Years ago IBM reshaped its business to be more services driven, which allows it to embrace new trends like open source enthusiastically. And even Oracle has built out a considerable cloud business (despite starting years later than it arguably should have), to which it can move current customers. Microsoft has been doing the same, transitioning customers to Office 365 rather than lose out on customers moving to Google Docs.

But the revenue profile for these businesses differs significantly from the traditional license/maintenance business, and it’s an open question whether any of these companies will be able to turn the corner in their current form.

The Wall Street Journal echoed this sentiment, suggesting that Oracle’s “business is being eroded at the edges by smaller, more focused companies offering newer technology,” and, I would add, by the very different business models these firms employ. It’s a great time to be in enterprise technology…so long as you’re not selling a legacy business model.

Image courtesy of Shutterstock.