ReadWriteBody is an ongoing series where ReadWrite covers networked fitness and the quantified self.

MyFitnessPal is a daily habit for me: Throughout the day—or at least before I go to sleep—I log all the food I consumed and all the exercise I performed. As I’ve added new fitness apps to my routine, I’ve noticed a trend: They all seem to be adding direct connections to MyFitnessPal, so I can track calories without all the extra work.

Just the other day, I got a notice from Pear Sports, my favorite heart-rate graphing app, that I could now pipe my calorie data directly into MyFitnessPal. And FitStar is in the process of adding MyFitnessPal support, both companies have confirmed to me.

When I remarked on this wave of connectivity to MyFitnessPal CEO Mike Lee on the phone recently, he was nonchalant: “It’s nothing shocking,” he said. “We’re the largest [fitness-tracking app] and we’re growing faster.”

You have to know Lee, as I have for years, to understand that this came across as a statement of fact, not a brag.

It’s also something I’ve been asking Lee about since our first conversation in late 2010. Mostly I gushed to him about his app, which had helped me lose 83 pounds. But our conversation ended with a complaint: Why can’t all these fitness apps just get along? Why do I have to enter the same data so many times into all of these different apps?

The Rise Of Fitness APIs

That was in late 2010, when the digital-fitness space was just getting going. Lee’s company—then barely more than him and his brother Albert—was struggling just to keep up with the explosive growth of its user base. Back then, my workout-tracking app had no way to talk to MyFitnessPal, meaning I had to enter the calories I burned in the gym twice. GPS run-mapping apps were in a similarly noncommunicative state.

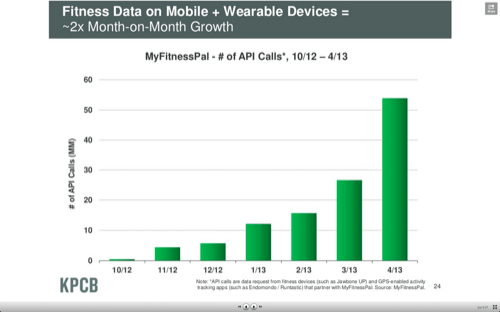

Things changed quickly. First RunKeeper launched its Health Graph API, or application programming interface, in 2011. Then MyFitnessPal unveiled its own API in the fall of 2012, inviting other apps to feed in calorie data. In less than six months, the number of API calls—requests made by apps to pull data from or feed data to MyFitnessPal’s servers—grew from nothing to 54 million by April 2013. (API usage has grown since then, Lee told me, though changes in tracking methodology make direct comparisons difficult.)

In August, MyFitnessPal drew $18 million in its first outside investment. And in November, Under Armour spent $150 million to buy MapMyFitness, which is known for its connectivity to other apps and devices (and also counts Under Armour CEO Kevin Plank as an enthusiastic user). You could say it’s proof of the value of having the right connections.

Mobiles + Wearables = Connections

What drove this API explosion? First came mobile apps. Once a company does the engineering work to have iOS and Android apps talk to its own servers, it’s not too much extra effort to open that up to outside developers.

But in the fitness space, the rise of wearable devices tracking steps, heart rate, and calories sparked a particular need for openness. Doing one-off integrations with every device out there—especially when there’s no clear winner in a crowded market full of Jawbone Ups and Nike FuelBands and Fitbits of every imaginable size and shape—would drain the resources of any app maker.

Now it seems MyFitnessPal is leveraging the growing size of its user base—more than 45 million, at last count—to spread its connections far and wide. It’s no longer limited to just tracking calories. Pact, an app which helps users place bets with themselves that they can stick to exercise and nutrition regimens, now pays you if you log your food religiously on MyFitnessPal.

Brains And Brawn

The next step for MyFitnessPal and other fitness apps is to go beyond tracking to making helpful suggestions. Lee says users have asked MyFitnessPal to have the app “nag” them—a request he’s mostly resisted, since MyFitnessPal’s unobtrusive approach has worked so far. (The mobile app recently added reminders to log my food around mealtimes, though the feature required me to opt in first.)

That may change, as MyFitnessPal gets more confident about what it can do for its users.

“We want to make the process of getting healthier easier,” Lee said. “When the motivation is higher than the barrier, that’s when consumers succeed. We’d like to get more proactive.”

The more that my apps do for me, talking to each other via APIs, the less work I have to do with my phone—and the more work I can do on my body.

I’m intrigued, for example, of the prospect of fitness apps like FitStar or RunKeeper forging tighter links with MyFitnessPal. What if FitStar boosted the time or intensity of a workout on a day after I overdid it on food? Or what if MyFitnessPal recommended that I get more carbohydrates in after a particularly grueling RunKeeper run, to replenish the glycogen in my muscles?

We’ve taken a giant leap since 2010, when fitness apps existed in their own silos and wearables were barely a glimmer. But we’ve just started to figure out where these new rails of connectivity can take us.

Photo by Shutterstock