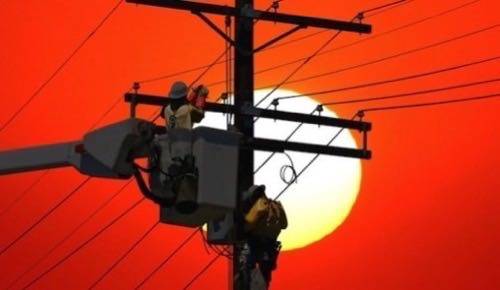

Recent blackouts in the U.S. and India should serve as a wake-up call to an increasingly networked world. Power outages are no longer a local problem. Mission-critical websites and data centers are increasingly likely to be located in blackout zones. Today, a local blackout can become a global business catastrophe.

That was one of the lessons learned on June 29, when a massive line of thunderstorms went derecho and plowed through the U.S. midwest and eastern seaboard. By the time the front’s powerful straight-line winds reached Virginia, dozens of people were killed or injured and millions were left without power.

Also knocked out was the Amazon Web Service data center in Ashburn, Virginia, zapping hundreds of websites and quite a few popular online services, including Netflix, Pinterest and Heroku.

Just one month later came the widespread blackouts in India. On the first day, the power grid in the northern India states went down, affecting an estimated 400-500 million Indians. As though that weren’t brutal enough, on the next day the eastern grid crashed as well, plunging another 100 to 150 million people into darkness.

U.S. & India: Different Issues, Similar Vulnerabilities

While the outcomes of events in the U.S. and India were similar, the causes were very different. Mother Nature was the primary cause of the U.S. blackouts, but she played only a supporting role in the Indian outages.

“The problem in India was mismatched supply and demand,” explained Prasad Dhond, marketing manager for Texas Instruments Smart Grid technology.

The biggest challenges facing India are meter tampering and other forms of electricity theft, Dhond explained, “Theft is very rampant in India.” That, coupled with a dry season that has reduced hydropower production, created a perfect opportunity for the grid failure.

The Failing Grid

The issues are different in the U.S., where supply is abundant and cheap enough that incidents of power theft are very low. In the U.S., the problem is high demand, high supply, and an infrastructure that was built to handle a smaller load.

According to the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), the U.S. needs to invest $107 billion in the power infrastructure between now and 2020 just to keep up with demand – a sizable $13.4 billion per year. Only 11 percent of that investment would go into generating more power; every penny of the rest would go to transmission and distribution.

“Without new investment, service interruptions and capacity bottlenecks will contribute to more frequent and unpredictable service interruptions that impose direct costs to businesses and households,” the ASCE said in a press statement last spring. “Those consequences will cost households $6 billion in 2012, $71 billion in total by 2020 and $354 billion in total by 2040. Businesses will pay $10 billion in 2012, $126 billion in 2020 and $641 billion by 2040 in avoidable costs.”

Even as U.S. utilities wrestle with infrastructure investment, private companies are contributing their own solutions.

Getting Smart About Power

Texas Instruments (TI) is in the business of making semiconductors, but it’s also building a market in energy management systems. These systems scale in complexity, depending on the infrastructure they’re serving. In India, for instance, the first stage might be to deploy tamper-resistant meters that would set off an alarm is a meter cover were removed or if the load balance between the live and neutral wire were way off.

In other nations, Prasad Dhond explained, sensors on the grid could give better warnings of problems on the system, and even help introduce better substation automation for utilities. This would scale up to smart meters that would handle what Dhond describes as demand-side management.

This is the kind of technology that consumers would see in their homes. Power indicators tied to appliances or stand-alone, in-home displays that would help power customers see their consumption rates and proactively manage their consumption.

“There are lots of smart meters in use in Texas and California,” Dhond said, though the real-time reporting is not quite there yet. In Texas, the meters report back consumption 6 to 8 times a day, and the results are reported on a public Web site. The data are about 24 hours behind, but it’s enough for customers to start identifying their useage patterns.

The need to manage demand could be critical, Dhond emphasized, because the U.S. is increasingly shifting its attention to electricity for energy. Electric cars are on the rise, but Dhond says a concentration of electric cars charging in a neighborhood might be a huge stress on the local grid.

The biggest challenge for power management is awareness. Right now, there’s not a perceived problem.

“Electricity prices are reasonable here in the U.S.,” Dhond said. “If they go up, interest in power management will go up.”

Hopefully the next wake-up call will be a mild one, and not a full-blown disaster.

Image Courtesy of Shutterstock