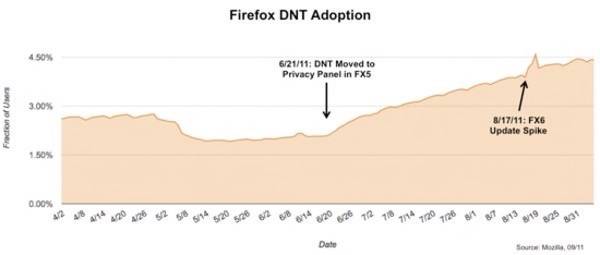

Yesterday the Mozilla folks released numbers and a “field guide” with sample code, tutorials and additional resources on Do Not Track (DNT). How’s DNT doing so far?

According to a post by Anurag Phadke a bit less than 5% of Mozilla users have turned on DNT. This might be a bit low because the tracking for DNT is by IP address. So users that are behind a firewall that exposes only one address shows up as only one user – even if 5,000 users are behind the firewall.

Slow Adoption

This is after just a few months of DNT being in Firefox, so the slow adoption is not a surprise. It’s not on by default, and many users probably don’t know it’s there or understand the implications. Even if they do, it’s not like DNT is going to be universally effective.

The field guide Mozilla issued, and its accompanying post make this ineffectiveness pretty clear. In the guide Mozilla acknowledges a few problems:

- Chrome does not implement DNT.

- All browsers have different interfaces for enabling DNT.

- Mozilla expects “approximately half” of users to have upgraded to a DNT-compatible browser.

- Support for DNT is voluntary.

- The browsers could diverge in the future on DNT support.

- The definition of “tracking” is not well-understood.

To help bolster adoption, Mozilla’s field guide has case studies that explain how various companies (a “technology provider,” “advertising company,” etc.) have implemented DNT so far. They also provide code samples that might help.

Its Bark Is Worse Than Its Bite

Unfortunately, DNT has no teeth. There’s no way to force sites to honor the header. In fact, the sites that will honor the DNT headers are probably the sites that users are least concerned about tracking them. It’s also deeply unclear what it means to be tracked, or not. Here’s what Mozilla says in its field guide:

“There are many different definitions of tracking that have been published. You may find it useful to read some of the additional resources at the end of this document. For example, some advertisers are calling for “Do Not Target” rather than “Do Not Track,” allowing data collection to continue unchanged. However, the original FTC staff document called for limitations of data collection, not just data use, after users express a Do Not Track preference. FTC Commissioners and staff continue to discuss Do Not Track as pertaining to both data collection and use.

“Another point of contention is whether DNT applies to first-parties as well as third-parties, plus disagreement on what a first-party is. For example, are widgets like the Facebook Like button first-party or third-party? Are analytics companies bound by that are contract not to use data beyond analysis for their clients to be treated like first-parties?”

Get the picture? Don’t get me wrong – I love the idea behind DNT, but the implementation is wholly ineffective. So much so that Firefox ought to include a big warning in its privacy preferences lest users be lulled into a sense of complacency. Another suggestion for Mozilla and other browser vendors that support DNT? Include a big warning for Web sites that don’t honor DNT settings.

What do you think? Is Mozilla barking up the wrong tree with DNT, or is there a good chance that it will catch on and be effective? I’m not convinced so far.