This is the third part of ReadWrite’s four-part series on the future of messaging.

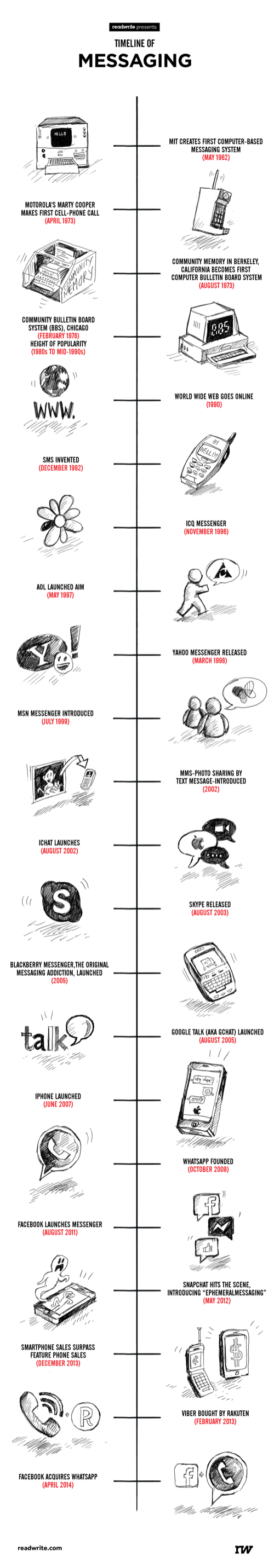

In 1961, a group of computer scientists at the Massachusetts Institute Of Technology created a system where multiple people could share computer resources at once. At the time, access to computers was extremely limited. The notion was to share a scarce resource and store shared files.

Along the way, though, the MIT team more or less accidentally created a way for users to leave messages for each other.

Called the Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS), the system was primarily used to write and debug code, but it would spread across Boston-area colleges as a messaging system for close to the next decade.

See also: Why We Need Messaging Apps

We’ve always turned new technologies into communication tools. Dial-up bulletin board systems, or BBSes, were popular in the 1980s, giving way to the interactive chatrooms of Prodigy, AOL, and other online services in the ’90s.

Text messaging untethered our communications. And with the rise of the smartphone, messaging apps usurped traditional texting as a way to chat with friends.

What’s important to remember is that scrappy upstarts like WhatsApp and Snapchat didn’t come out of nowhere. Their forebears, like AIM and BlackBerry Messenger, laid the groundwork for their explosive popularity by training us to send short electronic messages to each other.

Messaging is now the hottest commodity in technology as companies contend to be the service that controls how you communicate, leading to the fierce messaging wars taking place in 2014.

But how did we get here? We’ve noted some of the biggest points in the mobile messaging saga that’s driven apps to fetch massive price tags, and, now that smartphones are more popular than feature phones worldwide, the app economy will only grow from here.

Lead image by Jim Pennucci; timeline illustration by Madeleine Weiss for ReadWrite