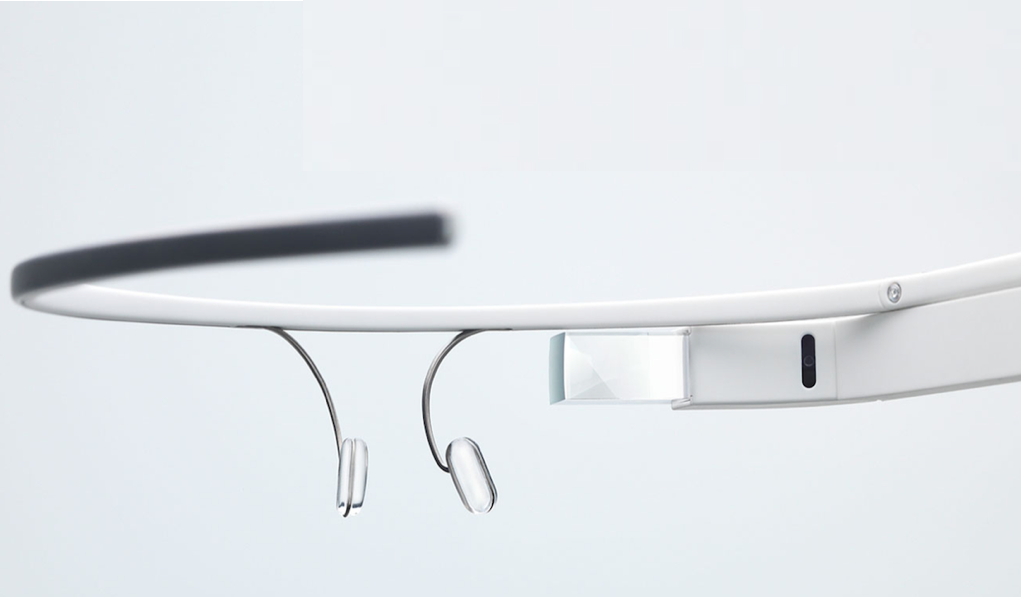

Even as many in the geek-o-sphere drool in anticipation for the onset of Google Glass, some technologists are starting to question the very real privacy issues entangled with the use of these wearable computers and cameras.

Predictably, the first concerns raised about Google Glass were about the user’s privacy: If I am transmitting all of this data to Google, it is going to know even more about me than ever! Or so the reasoning goes. I have to admit that this has been bugging me, but since I carry around an Android phone already, I’m pretty sure Google pretty much knows whatever it wants to know about me.

But then there’s the other half of the privacy problem, which not many in the community have yet voiced: What about the privacy of the people these devices are looking at?

Anonymous Cameras Everywhere

Being monitored by video cameras is nothing new, of course; it’s a risk we run every day. If I happen to absent-mindedly pick my nose in the seemingly empty frozen food aisle at Mega-Mart, it’s a pretty sure bet that my gross-out was captured on a video somewhere.

The advent of Google Glass supercharges the equation, because now the number of cameras increases – perhaps exponentially – and they’ll show up in ever more unexpected places owned by a much wider variety of people and organizations.

For now, there’s an implied trust that someone from the store won’t take that nose-picking video and put it on YouTube as part of a “Disgusting Things Journalists Do” montage. Sure, there’s nothing really stopping some bored Mega-Mart employee from scraping that video for whatever purpose. But, should they happen to post said video and I happen to see it, I will likely recognize my surroundings in the video and find someone to sue.

Now imagine the same situation, recorded not by the store’s cameras, but by someone wearing a Google Glass or similar device who happened to be standing unnoticed at the end of the aisle. Our voyeur records the incident, posts it on the Web anonymously, and –boom! – my reasonable expectation of privacy is violated. And I will likely never be able to find the culprit to take the video down.

The lesson here – beyond “don’t pick your nose” – is that if these devices do indeed take off, there is nothing to stop someone from monitoring and tagging me in photos, microblogs or videos – whether or not I know what’s going on.

There can be some positives out of this kind of citizen “Eye in the Sky.” If someone commits a crime, for instance, they might have been surreptitiously recorded in the act, with less obvious danger to the recorder than holding up a smartphone. Indeed, in his novel Earth, futurist David Brin outlines a near-future where citizens keep down random street-crime just by the existence of video recording equipment they wear.

But there’s a flip side to this, when a collection of Brin’s characters, a group of street punks, is befriended by an elderly man who seems to want to teach them about the Way Things Were. It all goes well, until after the senior man’s death, the gang discovers to their mortification that the man has been logging every conversation for use in a social-observation article about the state of youth in that society.

A little out there? Maybe so, but how long before Tumblr, Flickr and YouTube are filled with text and video content of embarrassing moments captured by Google Glass?

Anyone Can Be a Target

Beyond the voyeur problem, I keep coming back to how this technology can be abused – particularly this very scary scenario:

Imagine someone builds an app that lets you upload a photo of someone to your Google account and then uses facial-recognition software to process the face of every person you see. Sure, there are benign uses for such a tool, such as helping people remember the names of the people they meet.

But what if I was a member of an (alleged!) criminal organization who would love nothing better than to… talk… to the witness that’s going to testify in the trial that might prove my organization has done some pretty bad things. We’re innocent, of course, but it would be nice to… explain things… to this witness, who is currently ensconced in the U.S. Marshall’s Witness Protection program.

To find that witness today, I’d have to be incredibly lucky, hack the Marshall’s computer system or bribe (or threaten?) a corrupt law enforcement official. But in a Google Glass world, I could hire private detectives to be on the lookout for my target. Better yet, I could post an ad on Craigslist offering a reward to find “my long-lost cousin/uncle/aunt.” Now I have an entire community of people using facial-recognition software helping me find this person. Heck, you might not have to actively employ Google Glass users. Just periodically run a Google Image search of your target’s photo for “Images Like This.”

Now imagine you’re the witness in this scenario.

There are lots of times people don’t want to be found – spouses seeking to escape an abusive partner, victims trying to elude stalkers – any one of these types of people could run afoul of these cameras. The technology to do this kind of illicit activity is not quite ready for commercial shelves yet, but the day is soon coming.

But the implications are already disturbing: besides embarrassing videos taken in public, you can add tracking by jealous spouses, overprotective parents or insurance companies to the list. If you’re really paranoid, think about government surveillance of legitimate but unpopular activities.

Is this all too much? Maybe. But think about this, because as a father, I sure do: With Google Glass, what’s to stop anyone from recording images and audio of children? As a parent, the thought of anyone tracking minors for any reason without parents’ permission (unlike the kids in the image from the official Google video above) is abhorrent and potentially dangerous.

The technology itself makes this kind of subtle, continuous recording more likely. Unlike cellphone cameras, Google Glass is always on, always recording, capturing even the quick stuff you can’t anticipate. The upshot? Far fewer safe refuges where you’re not going to be recorded.

Ready For Your Close Up?

Plenty of others are worried about how Google Glass will destroy the expectation of privacy in our normal, not-made-for-TV daily lives. Mark Hurst at Creative Good writes (emphasis his):

“Google Glass is like one [Street View] camera car for each of the thousands, possibly millions, of people who will wear the device – every single day, everywhere they go – on sidewalks, into restaurants, up elevators, around your office, into your home. From now on, starting today, anywhere you go within range of a Google Glass device, everything you do could be recorded and uploaded to Google’s cloud, and stored there for the rest of your life. You won’t know if you’re being recorded or not; and even if you do, you’ll have no way to stop it.

“And that, my friends, is the experience that Google Glass creates. That is the experience we should be thinking about. The most important Google Glass experience is not the user experience – it’s the experience of everyone else. The experience of being a citizen, in public, is about to change.”

Whether we are just running errands, hanging out with friends or are on the lam from some really bad people, Google Glass has the capability to push our lives into reality of the television kind. But many of us aren’t ready for our close up, and never will be.

Images courtesy of Google.

Author’s Note: An earlier version of this story mis-identified the author of the Creative Good article as David Hurst, when it is actually Mark Hurst. The identification has been corrected.