Writing an app that will run on more than one software platform—think Windows, OS X, Linux, iOS, Android and Windows Phone—has usually been an exercise in frustration for developers, because it meant creating separate versions for each respective operating system.

But a long-awaited technology from Google may take a big step toward eliminating that headache by allowing Web apps to run on top of browser technology, not the underlying operating system. And without the need for an active Internet connection.

The Vicious Cross-Platform Circle

The time and energy it takes to “port” an app from one platform to another is clear from the fact that many developers and their accountants often decide not to port apps. If the numbers say it’s not worth the effort, then it won’t get done.

That’s why, for instance, there’s still no official Instagram app for Windows Phone. With just a 3% market share, Windows Phone is simply nowhere near as attractive to developers as iOS and Android. Sure, there may be Instagram on Windows Phone someday, but it’s clearly not a priority.

The problem is self-perpetuating, too. If a platform doesn’t have the apps people want, that makes it less attractive to would-be adopters—ordinary consumers, in the case of smartphones. This is arguably one of the big reasons Windows Phone remains marginal in the smartphone market—and why Linux has likewise failed to have much impact in the desktop/laptop world.

Developers have long hoped for rescue by Web apps—software that resides in the cloud and runs in browsers, a la Google Docs. Hopes were high that improved HTML and scripting technologies would allow a vast number of apps to run in a variety of browsers. Since browsers are already ubiquitous on most any platform, that would seem a handy solution to the problem of cross-platform deployment.

That has in fact worked, but only to an extent. For one thing, a Web app was basically just a Web page that had to be launched within a browser. There were workarounds—Prism for Windows and Fluid for OS X, for instance, made it possible to make Web apps look more like desktop apps, complete with icons you could click to fast-start Web apps. (I use Fluid to start up my Feedly instance in the morning, for instance.) Or users could make URL shortcuts. But such complications still limited Web apps’ appeal.

A second problem was harder to work around. By definition, Web apps require users to be, well, connected to the Web. That makes them basically useless if you’re not in Wi-Fi range.

Tethering Web Apps To The Desktop

No browser or platform team is as committed to the idea of Web apps as the folks at Chrome and ChromeOS. For Google’s developers, Web apps are central to the whole idea of Chrome and ChromeOS, which is to have developers write one Web app that can then run on any operating system where Chrome runs.

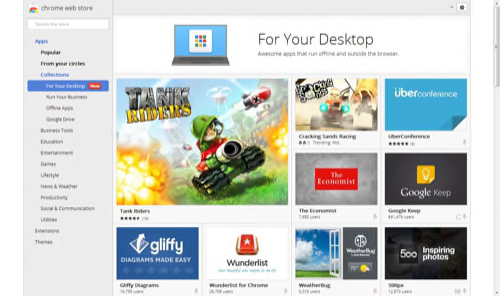

This week, on Chrome’s fifth anniversary, the team introduced a new twist known as Chrome Web Apps that aims to solve the two main shortcomings of “traditional” Web apps.

Built with HTML5, JavaScript and cascading style sheets, Chrome Web Apps open in their own windows, not the browser. But these apps will work offline and can use hardware (memory cards, cameras, drives) connected to the device they’re running on—something that traditional Web apps can’t do. The browser itself doesn’t even have to be running, although the apps will tap into its native functionality.

Chrome isn’t the only browser team working on this sort of packaged Web app software. Mozilla has made Open Web Apps available since 2011 in the the Firefox Marketplace. The Mozilla team has indicated that it has been working closely with the Chrome team to maintain standards capability.

There are, however, a few obstacles to Google’s vision. Chrome Web Apps are currently only available for Windows and Chromebooks, with Mac, Linux and mobile versions coming “soon.” And you probably shouldn’t expect to see these apps on Apple’s closed iOS platform any time soon—if ever. On iOS, Chrome apps would have to use the same Webkit rendering engine that Apple’s Safari uses, which means they’re unlikely to work.

Update: A comment to this story apparently from Google’s Joe Marini indicates that this supposition about iOS is not correct. According to Marini, “Actually, our plan is in fact to allow these apps to work on iOS. We are working to implement support for Android and iOS via Cordova (PhoneGap).”

Plus, Chrome Web apps would have to go through Apple’s app store anyway. This point is important, because Chrome Web Apps are tied to the Chrome Web Store. So while you can theoretically create a Chrome Web app that could run on any other browser, you’ll actually need to deploy it through the Chrome Web Store to package it for delivery to users.

Such “packaged” Web apps might well usher in a cross-platform future once the kinks are ironed out. With any luck, Google’s commitment to open standards won’t turn out to be mere lip service, because if it is, developers might just trade the problem of which operating system to work with for the problem of which browser platform to work with.