In September 2010, the U.S. Senate debated the latest draft of a bill for combatting online piracy. You may think you’ve heard of this bill, but there’s a good chance you haven’t. It was called COICA. It had a provision that seemed strange, as though it belonged to another era.

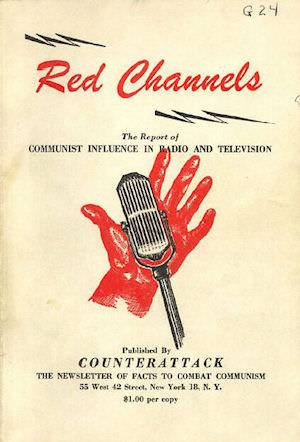

It called for the creation of some type of site or service that would publish a list of Web sites suspected of trafficking in illicit or counterfeit intellectual property. The hope was that someone might write a plug-in or a browser patch that would act the same way anti-porn filters work, by denying users access. The concept was denounced as a kind of blacklist.

COICA’s original sponsors – Sens. Patrick Leahy (D – Vt.) and Orrin Hatch (R – Utah) – defended the publication of suspected traffickers as a way of enabling the Web to police itself, saving a lot of work for the Justice Dept. Opponents, which included the Electronic Frontier Foundation, utilized what legislators call the “walks-like-a-duck” test: If the tool has the same effect as a blacklist – in this case, casting public disdain upon a list of possible suspects untried in a court of law – then it’s a blacklist.

Congress has debated some form of anti-piracy legislation for suspects on foreign soil for several years, usually with no conclusive results. 2010 was no different: The blacklist provision was killed, but the resulting bill still never made it to a floor vote.

But before then, the bill had spawned a popular opposition group that learned it could still make waves with an idea as old as anti-McCarthyism. When certain parts of COICA’s language were resurrected in the Senate as the PROTECT-IP Act the following year, the unpopular blacklist provision remained dead. But the cause that helped kill it lived on.

Legal experts cite two principal flaws in the PROTECT-IP Act and its House counterpart, the Stop Online Piracy Act, that could conceivably doom any legislation produced from them, even after being signed into law by the President: Arguably, it would place an undue burden on DNS service hosts to police Internet traffic, contradicting existing law (specifically, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act) which grants those hosts safe harbor when they do not police traffic. And serving such hosts with court orders may violate the terms of existing statutes limiting the extent of secondary liability for copyright violations. A third flaw, more technological than technical, is the obvious fact that shutting off resolution of a site’s domain name does not render it inaccessible.

Once lawsuits were filed against the government on behalf of the people, experts believe, judges unswayed by public opinion would likely notice these flaws and strike the law down.

But populist causes never rally around technicalities. What scares people is the idea of the blacklist, and its impact on the ideal of free speech. Opponents to SOPA argued last year that, once the Justice Dept. sought and received court orders to take down multiple domain names, the effect on free speech would be the same as a blacklist. If it walks like a duck, etc.

READ ALSO:SOPA, GoDaddy and the Bottom-Up Democracy (or Mob Rule) of the Web by John Paul Titlow

The bill’s proponents later amplified their promise that service providers cooperating with court orders would be granted immunity from prosecution. Their argument was that, although they may be in danger of losing DMCA safe harbor, they would be swapped out for new legal protections with the same effect. (If it walks like a duck, etc.) As a result, some providers signed on as SOPA supporters. One of them was Internet registrar GoDaddy.

The result was a wave of popular opposition against the registrar and threats of boycotts to its service, which immediately resulted in GoDaddy’s public reversal of its stance on the bill. But the populist cause that GoDaddy’s support had sparked, once again, lived on. One site now posts a public list of major Web sites that have not transferred their domains to other registrars since GoDaddy’s now-defunct support was made public.

The hope, apparently, is that someone might write a plug-in or a browser patch that would act the same way anti-porn filters work, by denying users access.

Support for this very idea has been building among users of aggregator site Reddit. “Someone needs to code up something like Ad-Block,” writes one member, “that notifies you every time you visit a Web site that is supporting the theft of our freedoms… Make it simple, and take it viral.”

Fear of where this and similar ideas are going, led Gawker’s Adrian Chen last Sunday to express his opinion, an act which an EFF analyst once explained to me to be the pinnacle example of something called “free speech.” “The thinking of the Internet hive mind is shallow and frantic,” Chen wrote, “scrambling from one outrage to the next.”

The response from Reddit members was such that it was impossible to separate the sarcasm from genuine madness. “Can we destroy Gawker for speaking ill of reddit?” asked one. “LETS TAKE DOWN GAWKER THISE SCUMBAGS WHO SUPPORT ALL THAT WE HATE,” wrote another. And there was this poignant addition: “Not all of us are like that or even follow what the hive mind says. Welcome to my block list.”

A method or methodology, it was explained to me more than once, that has the same effect as a blacklist in the public mind, is a blacklist. It walks like a duck.

Scott M. Fulton, III is the author of this document and is solely responsible for his content.