ReadWriteReflect offers a look back at major technology trends, products and companies of the past year.

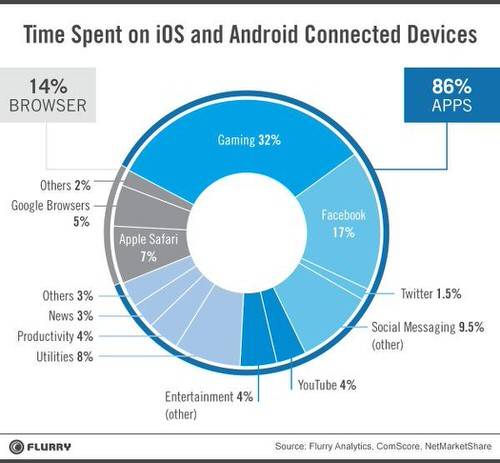

When we’re mobile, we’re social. In 2014, we spent 45 minutes a day on social apps on our smartphones and tablets—the biggest use for our devices after games, according to Flurry, the mobile-analytics firm Yahoo purchased this year. Social applications—social networks, messaging apps, and other forms of connection—now account for 28 percent of our time spent on apps, up from 24 percent in 2013.

Facebook still dominates our usage. But in many ways, the Facebook-defined paradigm for social networking fell apart in 2014. Social connections aren’t about one big place where we all hang out—it’s about a fragmented landscape of apps with connections that are more provisional than Facebook’s old friends list.

These changes aren’t lost on the Web’s dominant social network. Facebook itself has been a participant in and sometimes a driver of these changes. But the most interesting part of the social landscape of 2014 is the sense that it’s no longer just Facebook’s game.

Breaking Up Is Easy To Do—Even For Facebook

Smartphones, always pulsing with notifications and updates, break our attention spans down to mere seconds. The smart response by social networks is to break themselves into multiple apps, or for new apps to define their purposes ever more narrowly.

The app that epitomized this trend was Yo. Launched on April Fool’s Day, the messaging app only sent one word to your friends: “Yo.”

And Facebook’s standalone Messenger app brought the fragmentation trend to the masses. Some objected to its mandatory imposition, but it allowed us to converse with friends without contending with updates from our noisy news feeds. Standalone apps are like shortcuts to different social features that, on the Web, might make more sense as part of one big website.

“Connecting everyone means giving the power to share different kinds of content with different groups of people,” Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said in a conference call with analysts early this year. “This is something we focused on by launching separate mobile apps beyond the main Facebook app – Messenger and Instagram are great examples of this.”

Paper, a social news-reading app, and Groups, an app for Facebook-organized communities, are more examples of apps Facebook spun off this year.

Foursquare also pursued the break-up strategy, spinning off Swarm as an app just for location-based check-ins.

Messaging Dominated The Conversation

Facebook’s $17 billion purchase of WhatsApp focused everyone’s attention on the rise of messaging apps. Mostly free to use, these mobile alternatives to old-fashioned texting or desktop-based instant messaging attracted hundreds of millions of users. And there was no shortage of contenders, from WhatsApp to Snapchat, Line, Viber, WeChat, and others.

The reasons we used messaging apps in 2014 varied wildly, from the high cost of texting in Europe to the preference for visual communication with emojis in Asia to American teens’ desire for a less-permanent way of sending pictures.

The truth is that each messaging app serves its own purpose for connecting with people. The inherent complexity of human nature means that no one app will be able to serve all of our needs for connection.

The Rise Of The Anti-Facebook

This was the year we lost our innocence about Facebook. It was easy enough to ignore the abstract warnings about how the social network tracked users across the Web. It was harder to stomach the way Facebook researchers conducted a massive psychological experiment on almost 700,000 unknowing users for one week, tweaking the posts displayed in their feeds to make them happier or sadder.

There was also the incident where a disgruntled user sought to kick drag queens off of Facebook by reporting them for violating a rule that the social network rarely enforced.

Facebook executives apologized for both incidents, but together, they lay the groundwork for the rise of new social network Ello. Marketing itself as the “anti-Facebook,” creator Paul Budnitz promised an advertising- and tracking-free environment.

It’s not clear if Ello will ever attract a large number of users. But its very existence is a reminder that social applications must put users, not advertisers, first.

The End Of The Friend Request

Social applications are slowly but surely distancing themselves from one-to-one connections and the concept of the two-way “friend request.” Now everyone from Instagram to LinkedIn and Foursquare encourages users to “follow” other profiles.

“Following” people, celebrities, and brands that interest you gives networks more opportunities to grow than when they limit you to a small, finite pool of real-life friends or two-way connections. There’s less friction, too, in waiting for someone to accept a friend request.

No Names, Please

The ultimate form of connection we explored in 2014 was one where we didn’t ask for names. Secret, Yik Yak, and Whisper all took off, showing the strong interest people have in online anonymity. This, too, was a reaction to Facebook’s creation of a world where everything we do online gets attached to our name.

These experiments with anonymity had their downsides. Secret struggled with mean-spirited chatter, eventually putting in measures to keep users from including names in their posts. Whisper got in trouble when executives bragged to reporters about their ability to track posters.

It’s clear that anonymity or pseudonymity, in a throwback to the early days of the Web, are staging a revival. Even Facebook got into the game with an app called Rooms, which isn’t strictly speaking anonymous but instead uses instant-messaging-style handles.

What will 2015 hold? We’d love to hear your predictions.

Lead photo by Jason Howie