The two 24-year-old founders of the social app Yik Yak carry themselves cautiously. They leaned back in their chairs during their recent SXSW interview, sporting matching green socks adorned with their yak mascot. They remained very still throughout the one hour conversation, as though they wanted to disappear into the background.

This was the first big, live interview that Brooks Buffington and Tyler Droll had ever done, and it happened in front of an audience of about 500 tech enthusiasts and journalists. (And me, the discussion moderator.) Up to that point, they’d kept themselves out of the public eye, preferring to build their service quietly from their home in Georgia.

But Yik Yak is growing so quickly that it’s not clear how much longer it can avoid the usual dog-and-pony show the tech industry tends to force upon startups.

The App That Twitter Copied

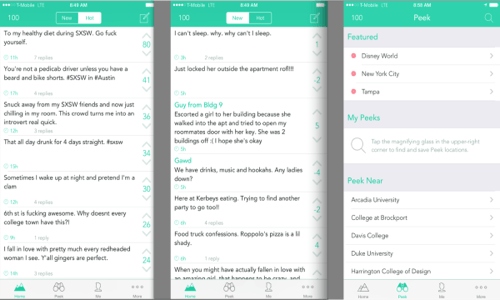

Yik Yak is a location-based social networking app that wants to be the next Twitter. It essentially broadcasts your posts to other users in a 10-mile radius, who can upvote or downvote them.

In the span of a year, Yik Yak has mushroomed into a social media giant. It’s a staple on every college campus in America; Twitter even paid it the compliment of ripping off its location feature. There are some controversies around the app, including allegations of cyber-bullying, but it also holds the potential of creating another new way for us to communicate with people—strangers and otherwise—who are physically near us.

Over the days and weeks prior to the SXSW panel, I had long conversations with the Yik Yak founders in preparation. What emerged from our chats was a picture of two cautious entrepreneurs whose success has come despite—even perhaps because of—their deliberate avoidance of the tech world.

Reporters Don’t Bite, Right?

As Yik Yak saw meteoric adoption on college campuses across America over the last year, Buffington and Droll avoided tech reporters as much as possible. I can personally attest to this; my texts and emails frequently went unanswered even after I interviewed them for a big feature last October.

On stage, they laugh nervously and shrug when I ask why they’re reticent to talk to the media. Buffington uncrosses his legs and smiles. “We didn’t grow up in San Francisco, our users are more in college,” Droll explains. “Our time is limited so we want to be focused on moving the brand within our core demographic.”

The duo might turn down interview requests from major outlets and tech publications, but they do a lot of college paper interviews. “Those are the real people that are using our app,” Buffington added.

The wariness has been mutual. Even as mainstream media outlets like the Today Show and the Washington Post flocked to cover Yik Yak, many in Silicon Valley remained diffident. They had seen too many high profile location networking failures before and grouped Yik Yak in with confessional apps Secret and Whisper.

It was dismissed as the last place contestant. A reporter friend of mine ruefully remembered his response when he was first pitched on the concept, “It’s an anonymous location-based social network based in Atlanta? Hahaha—good luck, Brooks Buffington!”

In the last few months, however, this narrative has reversed itself. Yik Yak raised $62 million in funding from prestigious venture firm Sequoia—a round led by Jim Goetz, known for making an early big bet on WhatsApp. Soon after, Secret redesigned its entire product to look like Yik Yak, and Twitter previewed a location based networking feature that was a blatant Yik Yak rip off.

In short order, the tech world started wondering “Is Yik Yak the new WhatsApp?”

It’s Peachier In Georgia

Buffington and Droll observed the melee from their perch in Atlanta. Most social networking apps either come out of the Bay Area, like Snapchat, or move there once they’re successful, like Facebook. Investors often insist on it. But Buffington and Droll held their ground when it came to such a negotiation. They wanted to stay in Georgia.

“We’re hometown heroes,” Droll said. “That’s where our families are, and that’s where we want to be. Why do we need to move?” The duo cites nearby universities like Georgia Tech as a source for recruiting engineering talent.

“Not every single engineer comes from California,” Buffington said wryly. In past conversations they’ve told me they like saving money on rent, cost of living, and salary expenses. They use their investment backing frugally.

Their reluctance to flee to Northern California, court tech press, and become part of the Silicon Valley startup world isn’t just a quirk. It’s Buffington and Droll’s secret weapon. With little knowledge of the high profile location failures that came before, Buffington and Droll lack both blueprints and fear.

Dead Apps On The Path To Success

The path to location success is littered with dead, dying, or stagnant apps—names like Foursquare, Gowalla, and Highlight. To attempt location networking yet again, and from the distant reaches of Atlanta, takes a certain amount of arrogance. But when I asked the Yik Yak duo why they thought they could succeed where others like Foursquare had failed, Buffington said something to the effect of, “Well, I don’t use Foursquare, so I’m not really sure.”

That fresh perspective is clear in their product design. They didn’t bother with check-ins or maps of people nearby. Instead, they applied a Reddit-like feed to the location problem. They focused on socializing and communication first, instead of gamification, which is perhaps what draws college students into the app regularly. People use Yik Yak to connect to people around them, not to collect badges or rewards.

Buffington and Droll are building for themselves and their friends, so they don’t spend time on concepts that might be relevant in the Bay Area but nowhere else. For example, when I asked whether they had thought about building for the Apple Watch, they looked at me like I was an idiot. “College students can’t afford the Apple Watch,” Droll said.

In that sense, the founders seem to be more in touch with their core audience then if they were building out of Stanford or MIT.

And Here Come The Me-Toos

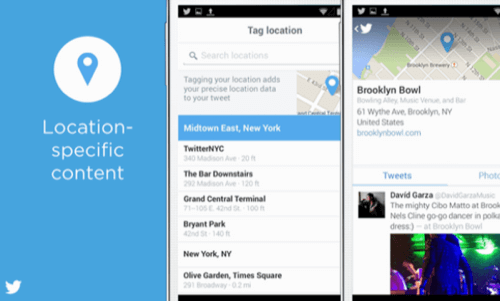

None of that has kept Silicon Valley darlings from trying to imitate Yik Yak, of course. Twitter’s upcoming location feed, which it previewed during its analyst call in November, looks almost identical to Yik Yak’s Peek Anywhere function. (That lets you beam into a different location to check up on conversation there, although you can’t participate.) With more money, users, and brand recognition, Twitter could theoretically beat Buffington and Droll to other demographics besides college students.

Not surprisingly, Yik Yak’s founders say they’re not worried about Twitter. (Do entrepreneurs ever admit if they’re worried?) “It was a nice shoutout from Twitter, but I’m curious to see how it plays out,” Droll said when I asked about it at SXSW. “It’s not core to their experience.”

Yik Yak benefits from being known as location first and foremost, but that very aspect of its product also limits its growth. People don’t have any incentive to get their friends in far flung places using it.

It has yet to expand beyond college kids, so it’s not clear whether strangers in a ten mile radius outside school environments will have enough in common. Location can unite people in powerful ways—whether you’re looking for a restaurant recommendation, want to sell something you own, or just need information on the weird parade happening outside.

In the meantime, Buffington and Droll are in no rush to expand beyond the university crowd. “That’s the most powerful demographic to have, college campuses,” Buffington said. “In a lot of ways, they’re tastemakers for not only America, but the world. Any large social network has to pass the sniff test by college students before it goes anywhere else.”

As the SXSW panel drew to a close, audience members stepped up to ask questions at the mike. It was college student after college student, professing their love of Yik Yak and thanking the founders for making the app. Buffington and Droll sat up a little straighter and started smiling. These were their users, the people they build for.

The rest of us are clearly just bystanders who don’t quite understand the Yik Yak phenomenon yet.

Photos by Juan Ramón Gomez, used by permission