The formal release of the final Windows Server 2012 this week sets up Microsoft for a showdown in the enterprise datacenter with its newly re-armored arch rival VMware. At issue is whether an operating system based on a consumer-grade client belongs in a server that runs thousands of virtual machines at one time.

Microsoft has not entered this battle unprepared. Small, mobile devices are the drivers of technology stories. Platforms are the drivers of technology. At the heart of Microsoft’s core marketing strategy for the past quarter-century has been faith that its ability to deliver a solid platform will secure its future as a software provider for devices, and vice versa.

From the perspective of device users, there appear to be two operating environments, and the crux of competition is therefore seen as an epic battle between Linux and Windows. This is about as accurate a picture of the data center as anyone’s perspective of Russia from his or her own front porch in Alaska. In reality, Linux and Windows Server are both common components of networked computing environments. We rely on both.

The Real War

In recent years, Linux has found its place as a bedrock foundation for network computing platforms. It’s small, carries less baggage, and is highly adaptable. Windows Server is, by comparison, bulky, although since 2010, its less graphically dependent Server Core option has rapidly gained favor, especially now that it can be managed from the command line using PowerShell. But every modern data center today uses virtualized workloads, because they’re more efficient, easier to manage, safer and more secure. Virtualization is the key to cloud computing – the addition of a layer of abstraction between software and hardware, so that applications run in an environment that is not constrained by operating parameters or location.

Windows Server vs. Linux is no longer the battle of the century, except perhaps in some comic book drawn by kids who wouldn’t know a data center if it abducted them from their parents’ basements. True, Microsoft is waging a market battle against Red Hat, but it’s not for control of the bedrock operating system of server processors. And Red Hat isn’t even the most awesome competitor here. That would be VMware, whose new CEO Pat Gelsinger hails from Intel, and who comprehends the dynamics of processors and their operating systems as thoroughly as any executive of any company, anywhere.

Gelsinger has thrown down a guantlet that aims to obliterate the present data center model, replacing it with components that render the processor OS either immaterial or non-existent. Windows Server would retain its strengths as a staging environment for critical business applications like SharePoint and Exchange, and systems like SQL Server. But that would be a tenuous position for Microsoft: remaking the image of Windows Server from a grounded platform to a floating raft, riding the waves generated by VMware and its growing network of partners.

While Microsoft would love to be able to own and operate the metaphor of floating on a cloud, it can’t afford to be perceived as floating on anything right now. So although the company did invoke its “Cloud OS” moniker (not really a trademark), during the formal premiere of Windows Server 2012, it had to present itself as rooted, as strengthening its own foundation, as extending the number of reasons why existing businesses should refrain from either investing in VMware virtualization platforms or experimenting with real cloud OSes – one of which happens to be produced by VMware.

“We built Windows Server 2012 with the cloud OS in mind,” remarked Bill Laing, Microsoft’s corporate VP for server and cloud, in a video released Tuesday. That’s a very carefully phrased metaphor – a bit like saying you’re cooking something with a meal in mind, as opposed to cooking a meal.

“Microsoft runs some of the world’s largest data centers and Internet-scale services,” Laing continued. “This uniquely positions Microsoft to pour all of that learning into our products, test them at scale and use our unparalleled experience in transforming data centers to address the needs and pressures of this new era of IT.”

The Package And The Payload

Laing went on to correctly define the modern data center as a provider of resources through services that are scalable to suit varying workloads, that can be pooled or shared so that they transcend location, that are perpetually available and backed up, and that can be effectively automated. That much is preaching to the crowd. But for Microsoft to reserve a place for itself at the table, it needs Windows Server 2012 to be a delivery vehicle for critical components of the data center, in a manner that parallels how Windows 7 and Windows 8 are, effectively, delivery vehicles for Office.

By “delivery vehicle,” I mean something that is delivered to the data center, that roots Windows Server in its existing location and hopefully lets it expand from there. In this case, there are two somethings in particular:

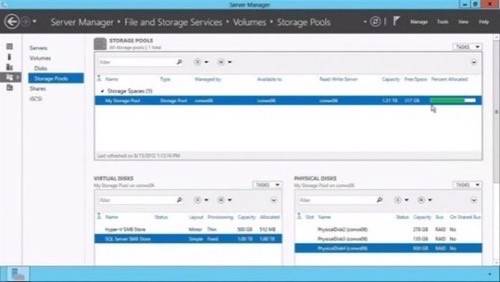

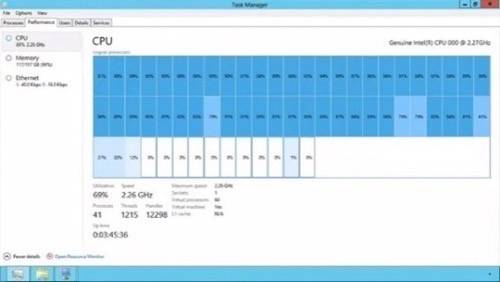

- Hyper-V is Microsoft’s hypervisor component – the part that enables an operating system (which can be scaled down to Server Core size) to run any number of virtual machines on behalf of clients. To that end, Server 2012 expanded Hyper-V’s statistical maximum capabilities dramatically: 320 logical processors per server, and up to 64 virtual processors per virtual machine (imagine an OS that thinks it’s running on quad-quad-quad core) with up to 1TB of addressable memory per VM. VMware’s ESX statistics may be comparable – assuming you want to go through the trouble of comparison, which requires fathoming that company’s arcane licensing model. While VMware holds the overall market share lead in virtualization, Microsoft continues to exploit its advantage with smaller businesses, seeding them with Hyper-V and growing them into customers the way it’s done before with SharePoint and SQL Server

.

- Windows Azure (probably just “Azure” at some point) is Microsoft’s public cloud, whose principal role has now officially changed from a Platform-as-a Service (PaaS) provider of .NET Framework services in the cloud, to an Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) host for virtual Windows machines. All Windows Server 2012 systems will include the ability to migrate workloads to the Azure public cloud, which does make Server 2012 to some degree a “cloud OS.” If Microsoft has one critical advantage over its competition, it’s the ability to introduce new capabilities to customers in small doses. Some folks are liable to try this out just to see what it does, whereas there’s no possibility of that happening with any other brand that requires a sizable up-front investment. Meanwhile, developers will continue to be able to deploy applications to Azure on a pay-for-use basis.

One important and impressive addition to Windows Server 2012 is worth noting here: By enabling virtual subnets that span geographies, you can create single subnet loops that span geographies. This way, if you have two data centers in different cities, you can live migrate a virtual machine between those data centers just as if they were situated right next to each other. VMware may offer similar capabilities – it’s not as though Microsoft invented this. But what you have to pay to get it with ESX is a significant talking point.

No Two Windows Servers Are Alike

In any discussion of server operating systems, one underappreciated aspect has been their roles. When Microsoft began endowing Windows Server 2003 with roles, it was with the notion that servers ran services the way clients ran applications. You want the server to do more, you run more services. You want more services, you add more servers. In those early days, the server operating system was somewhat monolithic. Today, think of roles like building blocks. When you select roles in installing Windows Server 2012, you’re assembling elements of the operating system. Different sets of roles make for a different operating system.

That fact is important in this context for the following reason: By successfully producing a single delivery vehicle for any number of various server roles, Microsoft has positioned Windows Server to compete with many tiers of products on many levels: against VMware and Citrix XenServer for virtualization, for instance, and against Red Hat for infrastructure and databases. This makes Windows Server one of Microsoft’s most successful and most critical strategic assets. It also places the operating system in a very tenuous position, because this capability centers around the notion that admins install it first. If admins install something else first, the game is over.

Almost nothing is challenging Windows Server’s qualifications to serve as an application host. But that’s not where the payoff is. For Microsoft to secure a permanent place for Windows Server 2012 in the data center over the next four years, it needs to make the case that scalability and versatility are not only feasible but practical with Server 2012 on the ground floor. If Bill Laing takes a trip to the ground floor anytime soon, though, he’s likely to find Pat Gelsinger already waiting for him.