Services like Foursquare, Gowalla and others make it easy to post your physical location to the Web – but what makes people want to do that at all?

Fifteen-month-old Foursquare is adding 100,000 new users every week, and Facebook has made it clear that location is a feature it is preparing to offer soon. What’s the motivation for users to register where they are in the offline world online? We asked some users of these services and found that they had varied and interesting answers.

Service May Vary

Of course, location services vary widely in nature. Nick Bicanic’s startup EchoEcho, for example, is a very discreet service for letting one friend know where you are at a time, emphasizing extreme ease of use. OK Magazine’s new celebrity-stalking location app might represent the other end of the spectrum.

Most people who shared their experiences with us were using one of the big social location apps: Foursquare, Gowalla, Google Latitude or BrightKite. Real-world businesses are starting to make interesting use of these services. (Here’s one list of 21 different examples.)

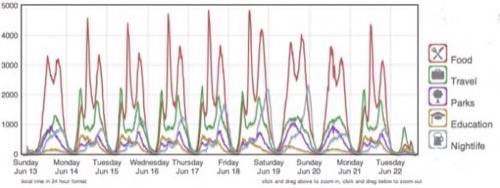

The types of places users check into are somewhat diverse, too, though the stereotype of Foursquare users as youthful bar-hoppers is largely confirmed by the numbers. According to a data visualization by the independent group BitsyBot Labs, bar check-ins on the service beat out check-ins at places of education and parks almost all last week. Bars were about equal with the arts and entertainment category. Food and shopping reign supreme, but on most days travel tops drinking, too.

Those numbers tell you something about aggregate activities, but why do individuals participate in this in the first place? It’s emotional, and it’s different for different people. Will location apps become far more popular once mobile coupons become ubiquitous, and people can save money by using such services? Maybe, but there are clearly other types of incentives already available.

Serendipity and Connection

San Francisco entrepreneur Pat Diven uses location-based social networks for probably the best-known reason, in the types of circumstances you might expect. He’s checked in on Foursquare more than 400 times, including at the bloggers’ event WordCamp, more than three times at an Apple store, and at more than 20 different pizza places. His Plancast account, where he records not where he is, but where he will be, indicates that he’s the kind of guy who likes both big tech conferences, as well as things like camping in Big Sur and beer and music parties in the countryside.

“I use location for chance meetups with people I know in the city,” he said last Friday afternoon via a Twitter client on his phone. “It’s worked a few times.” Diven also raised a common concern, articulated as a sophisticated social network user might: “Hoping for more granular control soon!” He’s a good example of an active person who both exposes a lot of their activity publicly and has entirely private accounts on other services.

Diven exposes enough, though, that I was able to see a lot of information about what he likes to do just by looking around online – I didn’t speak to him for this article beyond trading a single tweet. He’s been doing this for long enough (his Twitter account is more than three years old) that he’s sure to have decided that a certain amount of public exposure was worth it to him.

Cambridge-based experimental tech CEO Shava Nerad is on the other side of the country and has a different take on the use of location apps to connect with other people. She says for her, it’s simple. “I have friends who work in coffee shops and we like to spontaneously clump to co-work,” she said by iPhone early Saturday evening. “The rest doesn’t matter to me.”

Nerad’s public Foursquare history is much tamer than many people’s – though she did once win a badge for checking in after 3 a.m. on a weeknight, so apparently it’s not all about working.

Portland, Ore., consultant Mike M. says he uses location services to track people more than to meet them. His son works in emergency medical services, and Mr. M keeps an eye on him using Google’s service Latitude, “hoping he stays safe.” (I called him Mr. M. just because I don’t want to see his kid get in trouble.)

Location apps for tracking people around medical matters? That kind of thing makes many people take pause. Some of the same types of tracking technology are being incorporated into medicine and are in many cases causing a substantial reconsideration of patient privacy.

In the consumer world, it’s different. Last week I showed my dental hygienist who else was checked in to the dentist’s office on Foursquare at the same time I was, and her first reaction was concern about HIPAA (the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which regulates the security and privacy of health-related data). She decided no one could stop the patients themselves from exposing their own location; she just couldn’t confirm to me whether or not she actually knew who those people were.

Much more straightforward, in the people-connection department, was my wife’s comment left on Facebook last week when she got home and I was gone. I had checked into a coffee shop and pushed the update from Foursquare to Facebook, and she commented “there you are! I was wondering where you went.”

Be it for chance or as an exercise in caution, the uses of location services for tracking other people are just beginning to become clear.

For the Win

Many of the popular location-based social networks present themselves as games. They give points to users for going to new or multiple places, then tally the points up against the user’s friends. Does that really motivate people to check in? Does it motivate people to go to more or different places?

Apparently, it does. New York City author, social media consultant and mom Tamar Weinberg says, “people disagree with the concept of badges, but I think it’s fun to chase after new opportunity & status.” Hutch Carpenter, almost Weinberg’s exact opposite as an enterprise engineering platform executive and a dad in San Francisco, says he sees it that way too. “I second that,” he said of Weinberg’s explanation.

That ethos of location-based public achievement may go transgenerational, too. Carpenter checked in on Foursquare at Toy Story 3 this Saturday, said it was his 6-year-old son’s first trip to a movie theater, and pushed the update to Twitter.

This gameplay isn’t necessarily about narcissism. Virginia-based developer Alex Stone, who says he’s made several friends because of Foursquare, says of competing service Gowalla that “[its] quest for items and trip pins has led me to discover some really cool spots in my own small town.”

As a Personal History

The thing that surprised me most when I asked people why they use location-based social networks is how many of them say they use it primarily to track their own personal history. It’s a lazy diary, people say. I thought, naively, that I was the only one who felt that way.

Some people say they use it to help with their expense tracking on business travels.

Buffalo, NY, Web developer Adrian Roselli told me Friday that he started using BrightKite “so I could post photos in real-time while traveling and associating each with locations on maps.” He says he publishes the RSS feed of his check-in history to a map he can view later, to trace his route. That’s really geeky, but according to his check-ins, Roselli spent Friday night having dessert with a woman and Saturday morning on a charity bike ride. So apparently, you can push a check-in feed to a map and still maintain some connection to the kinds of things that normal people do. Several people told me they are doing technical things like that with their check-in histories for self-awareness.

When I went to New York with my wife earlier this month, she grew very tired of me pulling out my phone to check in everywhere we went. But once we got home, she admitted it was nice to be able to scroll back through the updates to Facebook I published and remember all the places we had been.

Or, as Palo Alto’s Spencer Schoeben told me this weekend, “I love looking back at my check-in history and remembering the awesome things I’ve done.” Schoeben is the 16-year-old founder of one startup company and CEO of another, so he’s recording a busy young man’s history with those check-ins.

Schoeben has reason to be proud of his accomplishments – and maybe we all do. The one rationale for checking in no one I talked to claimed for themselves – but that one very perceptive person quietly told me was probably more common than not – was showing off. “To non-explicitly brag about your coolness and/or importance, based on where you eat, drink, work, and travel.” That makes sense to me. Heck, I’ll own it myself, to some degree.

Did I feel a little cool when I checked in at Manhattan’s underground Ping-Pong venue and bar called SPiN New York and wrote “Crazy place, ping pong balls flying everywhere, hitting me while I drink beer and blog”? Yeah, I did. Was I aware of what I was doing the next weekend when I checked into two mid-century modern furniture stores in a row? Yes, throw me to the type of piranhas that eat people like me! I was aware of what I was doing.

There are clearly many different reasons people use location-based social networks. Many of us use them for several different reasons ourselves, at different times.

There are, of course, other sides of the story, ranging from the very serious to the somewhat serious. Dan Tynan wrote this weekend at IT World about why you should consider not participating in these kinds of services. Tynan writes a blog called Thank You For Not Sharing, which says it includes “a fair amount of whining.” (It’s really quite funny.)

Presuming you’re fully informed (though that’s another matter), then whether these services are for you comes down largely to your circumstances and your attitude. They aren’t for everyone. But they are a good experience for some people, as the stories above illustrate. If you’ve ever wondered why on earth someone would use a service like this – that’s why.