Facebook recently instituted a new program that makes it easy for 3rd party websites and services to automatically post links about your activity elsewhere back into Facebook and the newsfeeds of your friends. It’s called Seamless Sharing (a.k.a. frictionless sharing) and there’s a big backlash growing about it, reminiscent of the best-known time Facebook tried to do something like this with a program called Beacon. The company has done things like this time and time again.

Critics say that Seamless Sharing is causing over-sharing, violations of privacy, self-censorship with regard to what people read, dilution of value in the Facebook experience and more. CNet’s Molly Wood says it is ruining sharing. I think there’s something more fundamental going on than this – I think this is a violation of the relationship between the web and its users. Facebook is acting like malware.

It’s doubly bad because while the particular implementation of this feature has been executed so poorly, the fundamental ideas behind it have a lot of potential to deliver far more value from Facebook and the web to all of us. Facebook is experimenting with a trend that countless organizations will engage in soon: leveraging our passively created activity data. Why do they have to be so creepy about it though?

The Way it Works Now is Wrong

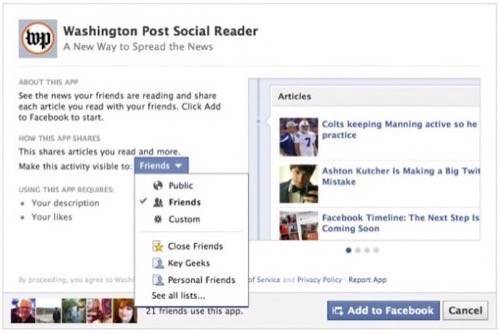

Facebook’s seamless sharing doesn’t just happen without notice. The way it works is that the user logs in to Facebook and finds news stories or other links from off-site posted to the top of their news feed. If they click those links, they are prompted to add a Facebook app from the publisher of the story so that their activity on other sites, be it the Washington Post, Yahoo News, or somewhere else, will also be posted back onto Facebook.

There are options available right away, like limiting who can see all those posted links, or opting to cancel addition of the app at all. If the user clicks cancel, they will be taken to the link they intended to click on anyway – they’ll just opt-out of adding the seamless sharing app to their Facebook account.

Got that? In order to do what you originally wanted to do when you clicked on a link, you have to click cancel on the menu that popped-up when you clicked on that link. That’s not unintuitive, that’s counter-intuitive. That it’s proven so wildly effective and feels like it caught people unaware makes it feel like an action taken in bad faith by Facebook – like you were tricked.

These options are no doubt skimmed over quickly by hundreds of millions of people who aren’t even familiar enough with their own computers to enter Facebook.com into their browser’s address bar without Googling for it and clicking on the link.

Violation of reasonable user expectations is a big part of the problem. When you click on a link – you expect to be taken to where the link says it’s going to take you. There’s something about the way that Facebook’s Seamless Sharing is implemented that violates a fundamental contract between web publishers and their users. When you see a headline posted as news and you click on it, you expect to be taken to the news story referenced in the headline text – not to a page prompting you to install software in your online social network account.

That hijacking of your navigation around the web is the kind of action taken by malware. It’s pushy, manipulative and user-hostile.

A Loss of Opportunity

In the near-term future, almost every action that you take at home or out in the world will be tracked and measured. Hopefully it will happen in aggregate and anonymously, with extensive privacy protections in place. In exchange for the instrumentation (making measurable) of everyday life, the world will be able to be managed in ways that are more efficient, hopefully more just, and more conducive to new innovations. When the traffic on every road is tracked in real time, for example, then new applications will be created to help drivers select the best route to work and for cities to manage vehicle emissions. Billions of devices will be connected to the network in the future and publishing data into a platform for application development – it’s important that those systems be built in a way that people can trust or else the whole scenario is going to be ugly and under-utilized.

Likewise, our activities online are already being tracked all the time – but in most cases it’s not our social selves that are attached to that data. We’re just numbers tied to history that gets referenced when it’s time to serve us up a personalized advertisement. Though some people find that frightening, I don’t think it’s a very big deal.

Where the new developments come in online is when that data is used to offer us value, not just advertisers who would track us. It’s nice when our music social networks, for example, can easily surface the albums that we listen to the most so they can be played with a click. It’s cool that music popular with our friends is surfaced as well. It might not be quite so cool when every song we listen to is pushed out to all our friends with our names attached. It is even less cool when those are articles we’re reading around the web, pushed out without our choosing to share a particular item. I’d like to see what articles are popular among my friends, but I don’t want particular friends self-censoring what they themselves read out of fear they’ll be associated with all of it individually.

“I’m afraid to click any links on Facebook these days,” says CNet’s Molly Wood. That’s one of the world’s top technology journalists talking; even she seems unclear on how the system works and would rather just avoid the entire thing.

There are good ways and there are bad ways that our “data exhaust,” the cloud of data we emit when we engage in everyday activities online, can be used to our own benefit. That data could be used to deliver us new recommendations for discovery, analytics showing us things about ourselves we never knew before because we couldn’t see the forest for the trees. When a giant social network does it wrong though, that puts the whole opportunity for everyone to do it well at risk.

I don’t know why the world’s leading designers on social media user experience would have made something as creepy feeling as the way this new seamless sharing was instituted, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s because behind the scenes Facebook is built by arrogant young people living charmed lives and sure they know what’s best for the rest of us. There’s something about new features like this and the way the company talks about them that feels fundamentally patronizing. Looking at the user comments that get posted on Facebook announcements, it’s not hard to imagine why, though. (They are really dumb.)

I think Facebook ought to put a greater emphasis on acting in good faith and helping its users make informed decisions, in line with their reasonable expectations, as the company seeks to experiment with building the future of media.