A few weeks ago, we reported on some demographic information about the first wave of Google Plus adopters. Bime, the data visualization firm who conducted the study, found that early Google Plus users were mostly young American men working in technology (surprise!). The Bime study used profile data from Find People on Plus, a third-party directory of Google Plus users, except for the age numbers, which were pulled from comScore numbers.

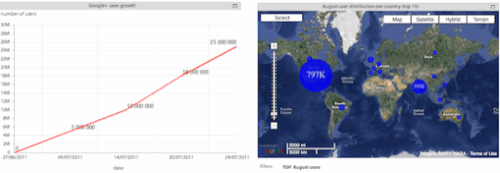

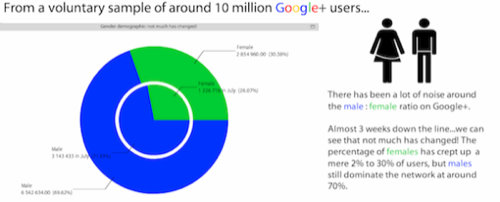

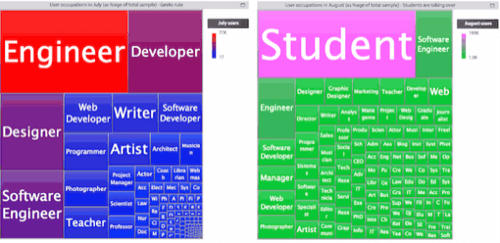

Bime has just put out an updated visualization that breaks down Google Plus demographics including the month of August, now that the service has had some time to grow. This survey covered 10 million users, more than twice the size of the previous one, and some things haven’t changed. About 70% of Google Plus users still identify as men, and the vast bulk of them are American. One major shift has taken place, though: While the updated post doesn’t have the age numbers (which came from a different dataset last time), the occupation data show that students have overwhelmingly displaced tech workers, though all the same tech jobs as before dominate the rest of the top spots.

Bime’s findings about the student takeover conflict with some research we’ve covered since the first Bime study, but the methodology of this Experian Hitwise study was a little strange. It tracked 10 million people by rather different measures, creating “word clouds” to identify demographics by the descriptor words they use for themselves. It found that Google Plus usage in its “Colleges and Cafes” demographic has declined significantly since launch, while “Seeking Singles” and “Kids and Cabernet” — defined as “Prosperous, middle-aged married couples living child-focused lives in affluent suburbs.” — have increased.

That would seem to totally contradict what Bime found. Bime uses self-reported data from user profiles, though, and this Experian Hitwise study, to the extent it makes sense at all, uses some highly advanced semantic analysis where simple profile fields would seem to suffice. So let’s assume that the huge growth in people calling themselves “students” is more believable than the decline in people using a cloud of words some algorithm defines as “student-y.”

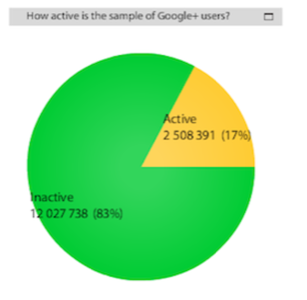

Two other trends jump out from the new data. User growth is steady and more or less linear week over week, but 83% of users in this study are classified as inactive. Bime doesn’t know how this is defined, so we’ve asked Find People on Plus for comment and will update with the response. Find People on Plus has admitted that its directory can only see public posts, which makes this measurement unjustifiable, and it is renaming this data field as a result. If it’s true, though, that means that only 2.5 million people from the sample are really using Google Plus. Furthermore, Bime admits that its own interpretation of the data was unclear. Out of this voluntary sample of 10 million, only 2.5 million are using the service. Neither of these studies seems dependable enough to draw conclusions about overall activity on the service. It was a voluntary sample, though it was still a large one, and the respondents were mostly male students and geeks (which, for the record, is a term of affection at ReadWriteWeb).

Are you on Google Plus? Has your use declined since you joined? Let us know in the comments.