Whenever a new Web trend comes along, there are people who ask, “What is the point of this?” If millions of people are using something, there has to be a reason. In our What Is the Point of… series, we’ll explain it to you.

This week, we’re asking, What is the point of Branch?

Branch is a new company guided by Obvious Corp, funded by Twitter founders Evan Williams and Biz Stone, that seeks to solve one of Twitter’s biggest problems. Twitter, and the whole real-time Web that has emerged along with it, is a great way to find information and a great way to share, but it’s a terrible way to have a conversation.

Conversations start on Twitter all the time, but they immediately pick up speed and become difficult to follow. The constraints of 140 characters are also too limiting for some ideas. So when Branch opens to the public, you’ll be able to click a “Take it to Branch” button in your browser and continue the discussion in a more suitable medium. Or start a new one.

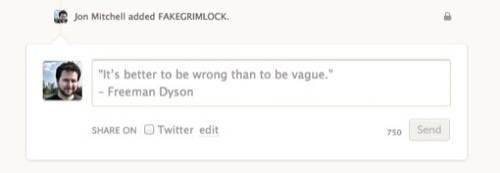

You can start a branch off of any link, not just tweets, and that initial spark sits at the top of the conversation. The conversation itself takes place on Branch, but it uses Twitter to contact people you want to invite. It sends a direct message if they’re following you and a public @ mention if they’re not.

It’s part of the fun to tweet links to the conversation as it goes on. People who see it mentioned on Twitter can dip in and out, and if they want to participate, they can ask to join.

Branch is roomier than Twitter, allowing 750 characters per message. That gives you space to compose a thoughtful answer. But if the conversation is too crowded, it can get out of control quickly, as we saw in our first RWW branch about the future of Web publishing.

There’s also no formal structure for replying to specific messages, so you have to come up with some way to make clear, in the content of your message, to whom you’re talking. If a branch starts a tangent deserving of its own conversation, you can create a new one off of an existing message.

(For now, since most people haven’t gotten full access to the service, they aren’t able to create their own branches this way. This is frustrating for people who have been invited to participate in an existing branch but can’t branch off from it, but it’ll be okay once Branch opens to the public.)

The decision of who to include in a Branch conversation is one of the controversial aspects of the service. The person who starts the branch controls who is invited, and each participant can also invite one person. There’s a trade-off between a conversation that’s orderly but exclusive and one that’s welcoming but noisy.

Our first RWW experiment went with the latter approach, letting in everyone who asked, because that’s more our style. But it was a bit noisy. We’ll continue to experiment with large and small Branch conversations as the service evolves and see what works best.