Ever since the term “Web 2.0” started to catch-on, people have been speculating as to what “Web 3.0” will be. Briefly stated, Web 1.0 was the Static Web and Web 2.0 is the Social Web (for more a more nuanced view of this history, see here). One popular theory is that the Semantic Web comes next. Others have also called for Web 3.0 to involve user-centric identity and data portability – technologies that would depend on many of the same open standards that would enable the Semantic Web. Others suggested personalization would be king.

We’ve covered all these subjects over the years, and it seems that the Personal Web is what’s taking hold. Look at Netflix recommendations, Gmail Priority Inbox, Facebook’s prioritized activity stream and, a little less mainstream, services like GetGlue, Hunch and My6Sense. I would also include the “Quantified Self” movement, which includes applications like Mint.com, Run Keeper and Rescue Time.

But we haven’t really seen the sort of openness many of us wanted from the Personal Web. The Attention Trust came and went. Facebook and Twitter are beating OpenID in the identity wars, and data portability on the consumer Web is still something of a pipedream. Lock-in is still king. But for how long?

The Doctor’s Diagnosis

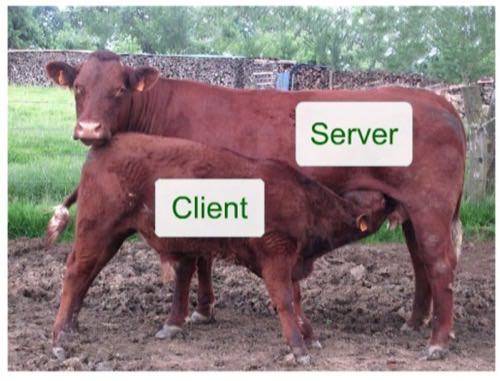

In a recent rant on his blog, Doc Searls comments on the entrenched client-server model of the Web. For those that have been following Searls for a while the message will be familiar. He uses this image to make his point:

So, while the Net itself has an end-to-end design, in which all the ends are essentially peers, the Web (technically an application on the Net) has a submisive-dominant design in which clients submit to servers. It’s a calf-cow model. As calves, we request pages and other files from servers, usually getting cookie ingredients mixed in, so the cow can remember where we were the last time we suckled, and also give us better services. Especially advertising.

We have no choice but to agree with this system, if we want to be part of it. And, since the cows provide all the context for everything we do with them, we have onerous “agreements” in name only, such as what you see on your iPhone every time Apple makes a change to their store.

Searls also rails against sort of agreements businesses impose on customers:

Here’s the thing: client-server’s calf-cow model requires this kind of thing, because the system is designed so the server-cows are in complete control. You are not free. You are captive, and dependent.

This system has substantiated a business belief that has been around ever since Industry won the industrial revolution: that a captive customer is more valuable than a free one.

Searls’ contribution to an alternative to all of this, is what he calls Vendor Relationship Management, an inversion of Customer Relationship Management in which customers control their data and contact information. Searls writes:

We won’t get rid of calf-cow systems, nor should we. They work, but they have their limits, and those become more apparent with every new calf-cow service we join. But we can work around these things, and supplement them with other systems that give us equal power on equal footings, including the ability to proffer our own terms, express our own preferences and policies, and make independent choices. […]

The message I’m bringing is not about how these companies can improve the cow systems everybody has done so much to build and improve already. It’s about how buyers and sellers are no longer just cattle, and how we now need to prove something we’ve known all along: that free customers are more valuable than captive ones.

The VRM Project, headed by Searls, defines VRM as “tools by which individuals can take control of their relationships with organizations — especially in commercial marketplaces.” We’ve covered it before and it’s been “the next big thing” for years. Maybe social business and social CRM are the movements that will make VRM a reality, but let’s face it: this may never happen.

We might not ever see a real VRM movement, but we might be seeing the decline of the captive customer and vendor lock-in sooner than later.

Vendor Lock-in and the Cloud

Oracle’s continued success would seem to demonstrate that captive customers really are more valuable. But the question is whether customers will choose to be locked in if they have a choice.

Companies like EnterpriseDB are staking their businesses on the idea that customers, given a choice, will prefer not to be captive. And there is real momentum behind open cloud standards (as long as we can avoid open washing), open source databases and, of course, Linux. Apache Hadoop is particularly disruptive because there is no viable proprietary alternative. SaaS makes it easier than ever to run pilot programs, and as long as customers can easily grab their data through an API, it’s all reasonably portable. For once, it seems like enterprises will have more customer freedom than consumers. Will that trickle down?

Keeping customers captive requires that all vendors play-along. Moving from one walled garden to another isn’t necessarily appealing, but what happens when you give customers the freedom to easily jump from vendor to vendor?

Lead photo by Steve Gibson