Smartwatches and fitness trackers now come in shapes and sizes to suit everyone, but the data they produce is all along similar lines: Step counts, activity times, sleep duration and so on. On more advanced devices, you might get some extra metrics, but the basics are the same.

Even two apps as disparate as Google Fit and Apple Health—different developers, different platforms, different user interfaces—report back a lot of the same information. One of the critical challenges for both manufacturers and programmers is making this data meaningful enough to keep users engaged and working on their fitness in the long term.

See also: Google Fit vs. Apple Health: Who’s Winning The Race?

For a deeper look at how developers can use this raw data to carve out something unique and compelling, we spoke to three people at the forefront of the wearable app revolution.

“Cracking The Social Layer”

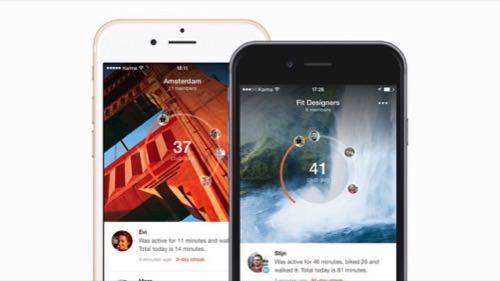

Paul Veugen is the co-founder and CEO of Human, a company working on both a personal app for setting activity goals, and a system of data visualizations spread across cities. For Veugen, the hard work starts once the data has been gathered.

“Both Android and iOS have a great foundation to access sensor data … but turning that data into more meaningful user feedback requires quite some post-processing,” he says. “Google Fit and Apple Health offer the building blocks to build a nice solid timeline of your day, but need to mature a bit more to offer a clean overview, especially for anything else than walking or running.”

“The biggest opportunity in our space is not solving the tracking puzzle,” adds Veugen. “I think it’s more interesting to focus on what makes people use these products in the first place: How can we shift data as much to the background as possible?”

Social could be the way in: “When people care enough about the gameplay and functionality, absolute tracking accuracy is not really a big deal. Cracking the social layer around health and fitness is a great challenge—it’s hard to find great examples in the health and fitness space that are social from their core.” Strava is one app that has social and gaming features that Veugen particularly likes.

As for the Human app, it focuses turning motion and location data into real-time insights: Veugen says the more accurate and more layered the data, the better the inspiration and motivational encouragement for users.

“We’re tracking about 100 million activities every month, and trying to turn these activities into insights about movement around you,” said Veugen, whose company shows real-time statistics for 900 cities around the world. “We’re building our community around activity,” he said. “We believe this data can not only be valuable to improve Human for our users directly, but can help to improve our physical world.”

“Connecting Multiple Datasets”

Siva Raj is the founder and CEO of Revvo, a startup looking at the science behind physical fitness and innovations in the field of the quantified self. By analyzing its users’ VO2Max level—shorthand for maximal oxygen consumption or uptake—the Revvo system aims to provide real-time, customized coaching advice.

Raj sees the biggest opportunity for developers in “creating real meaning by connecting multiple datasets” within an app, he said. “From the user perspective, despite the plethora of options available, the biggest challenge seems to be knowing what’s the right thing to do so you see quick progress to your goals.”

Providing tailored direction in the very moments that the end user needs it is the goal, but it’s not easy: “This is a challenging problem to solve,” he said. “People have different goals; they’re starting at different points; they need to train differently; they are progressing at different rates; they can each have different reactions to the same or equivalent training program … and of course lifestyle, motivation levels and preferences are all different.”

Ultimately, when such apps and their underlying platforms succeed, they act more like actual sports coaches or personal trainers, offering advanced feedback, but without the costly price tag.

“Today this requires an experienced coach and expensive or repeated measurements at a fitness lab—accessible only to elite athletes,” Raj said. “The question is can technology effectively support or substitute this at a lower cost so that everyone can benefit?”

Wearable hardware needs to improve as well, he added: “None of the available wrist and arm based monitors are consistently accurate when compared to the chest strap, and I think we’ve tested nearly everyone of them,” said Raj, who has noticed they can lag 20 bpm [beats per minute] on average, or fail to work at all for some users. “Accuracy matters,” he said, “particularly when you are trying to make real sense of data.”

“Finding Meaning In The Data”

Josh Sharp, co-founder of Exist, has his eyes on a more universal goal: giving users “a way to track and understand your life.”

Sharp believes “there are so many opportunities to do great things with this data that nobody has really nailed yet,” he said.

“Fundamentally, activity trackers are stupid—they react to physical activity and return you a number,” he adds. “If you look at this as low-level data, you see there’s so much opportunity to build on top of that to produce ‘high-level data’ … turning things like step counts into more meaningful information about your relative progress against your average day, for example.”

Making sense of the information is a high priority at Exist, which doesn’t simply collect raw numbers, but evaluates them to uncover trends and correlations.

Sharp also suggests using aggregated data to “build intelligence” into other apps. One of his company’s new features uses your recent step count history and the time you wake up to work out the likelihood of you reaching your goal on a particular day, before you’ve even started walking.

“Your music player could know what genre to suggest based on the time of day, your mood, and your current productivity levels, or your language learning app could go easy on you if it knows you had a really bad sleep last night,” Sharp said. “To some people, this sounds like a dystopian hell, I know! But I’m excited about all the opportunities here that people could be building right now.”

The sheer volume of data we keep about ourselves, already massive, will only grow as the IoT (Internet of Things) ecosystem matures. That will “spur an even greater need for tools that give that data meaning,” he adds. “Alongside the rise of cheap, ubiquitous Bluetooth location beacons, we’ll see new experiences based around ultra-local location and interaction tracking—knowing where you are and what you’re looking at, and even who you’re with.”

With social layers, multiple datasets, intelligent meanings, and more, there’s a lot for developers to explore. The challenge is now on to take those streams of data and build something unique and meaningful from them.

Images courtesy of Human, Revvo and Exist